Best of Blog: The Diverging Diamond

When a reader sent me a video of a guy extolling the pedestrian- and bike- friendly virtues of the diverging diamond interchange, it was Game On. What resulted was not just a video response and some (sometimes sensational) media coverage, but an in-depth analysis of how the standard diagnosis of traffic problems being volume, speed and capacity leads to one incoherent and costly solution after another.

While I wrote the series over the course of a month, it really should be read as one long article, which is how I've republished it today. This will also give you a little preview of the next report we are working to prepare, tentatively titled Misunderstanding Mobility, which will simplify these issues for the more passive reader. But for the hardcore, today in our Best of Blog series we present The Diverging Diamond.

Diverging Diamond Walking Tour (original video)

Tour of the "pedestrian friendly" diverging diamond (Strong Towns video)

A 45 mph world

We've built a 45 mile per hour world, one that moves too slow to be efficient yet too fast to provide a platform for value. Our transportation system embraces mediocrity, not from a lack of resources, but from a lack of focus. We must quit fooling ourselves, understand what it means to really create value in a transportation system and commit ourselves to building Strong Towns.

Seems like I've offended someone from every group at least a little bit with my commentary questioning the pedestrian friendliness of the Diverging Diamond Interchange (or DDI for short, as I've found out they call it in the biz). I'll take one comment from @cartographer1977 as representative of the criticism I think most important to address:

The problem is not the concept of the DDI but rather the poor pedestrian and bicycle facilities at this particular DDI.

The Diverging Diamond Interchange may be a fantastic way to move more auto traffic in less time and with more safety than using a standard interchange. One could also argue that the modest pedestrian facilities -- ridiculous afterthought though they may be -- are a step in the right direction, acknowledgment of the need to safely accommodate the long-neglected non-auto traffic.

The problem with these observations is that they are rooted in a fantasy world, one we've created for ourselves, complete with false metrics and all the confirmation bias necessary to avoid reality. It is tough to have an intelligent discussion on the DDI because, in order to do so, we need to step way, way back and truly understand our transportation system.

Let me start by pointing out one cold, hard fact: We do not have anywhere near the money necessary to maintain our current surface transportation system.

The Federal Highway Trust Fund is broke. Projections give it dimes on the dollar of what is necessary to maintain the systems we have created. Those problems simply roll downhill, and so our states are in a position just as difficult, if not more so. States, not having the revenues to maintain their systems or the ability to raise more revenue, have turned to debt to forestall the day of reckoning. Just look at Texas -- allegedly one of the country's most prosperous, as well as auto-obsessed, states -- and see how they have used debt to kick the can down the road.

As governor, Perry advocated the controversial Trans-Texas Corridor, an ambitious transportation scheme that relied on foreign investment and tolls for financing. It was abandoned after the outcry from property owners whose land would have been claimed by eminent domain.

Since then, the state has relied heavily on issuance of bonds to build highways. For the first time in history, the Texas Legislature this year appropriated more cash to pay for debt service than to pay for actually building new roads: $850 million per year versus $575 million.

Lawmakers also approved the use of $3 billion approved by voters in 2007 for road construction, but the Texas Department of Transportation estimates the state must pay $65 million in annual financing costs for every $1 billion it borrows through the sale of bonds.

The state began borrowing money in 2003 to pay for roads and will owe $17.3 billion by the end of next year, contributing to the rapid escalation of total state debt, from $13.4 billion in 2001 to $37.8 billion today.

The money will cover just a fraction of the transportation needs identified by planning experts. The Texas Transportation Institute two years ago placed the state's highway construction needs through 2030 at $488 billion.

The second fact that needs to be acknowledged is this: The system we've built is financially inefficient and unproductive.

This is where I'm going to lose a lot of engineers who believe that each part of "The System" can be inefficient and dumb yet, somehow magically when combined, "The System" overall becomes this awesome engine of American prosperity. This is the fantasy part I referred to earlier. What gives us this belief?

It can't be the numbers. We reported earlier this year how the American Society of Civil Engineers' own report showed that the costs to maintain the current surface transportation system at "minimum tolerable conditions" far exceed any of the benefits, even as they massively inflated the benefits.

And do we really believe, as just one example of many, that saving a few thousand cars from having to sit at a railroad crossing each day translates into $47 million worth of wealth created? We deliver ourselves a derivation of this lie every time we make a major transportation investment.

But go beyond the numbers. We build an interchange on a highway -- diamond or otherwise -- and what happens? We get a Wal-Mart, a couple of gas stations and a Pet Smart. Does anyone believe for a second that, without this investment, people wouldn't find a way to buy cheap imported goods, gasoline and dog food? The United States has six times the retail space per capita of any European country! There are diminishing returns here. We're long past anything that makes economic sense in a true market economy.

Go ahead and argue that if we simply paid more in taxes we could afford our surface transportation system. That is ASCE's argument -- we're a wealthy country, after all. Well, besides the fact that you would be living in a fantasy world (because it's not going to happen), it wouldn't help if it did.

Raise the gas tax enough to make a difference (we're talking $2 or $3 per gallon in Minnesota, according to people I've spoken with at MnDOT who have done the calculations). What would happen? People would drive a lot, lot less. We would then have the money to maintain a bunch a roads that people wouldn't be using -- not a viable long-term policy. Okay, how about switch to a mileage tax. Again, when you charge people by the mile you'll find that people will avoid paying the charge by reducing their trips, at least if the charge is anywhere near high enough to reflect the cost. Maybe you think people driving less is a great solution, but if you do, you can't be arguing that our money currently is well spent by expanding the capacities of "The System".

So maybe we should just take money from the general fund (incidentally, this is what we have been doing). In that case, there would continue to be no connection between what people want (more capacity) and what people are willing to pay (little to nothing) and we go right on building more in the current, unproductive model. The lack of productivity -- the lack of an ability to capture any financial return -- would ultimately catch up to us again (as it has now) and we're right back to where we started, only with even more of "The System" to maintain.

This leads to the third fact about our surface transportation system: Americans do not understand the difference between a road and a street.

(My recent TEDx talk was on this very topic, although there is only so much you can say in 15 minutes' time. I'll elaborate more here and in an upcoming report we are working on.)

Roads move people between places while streets provide a framework for capturing value within a place.

The value of a road is in the speed and efficiency that it provides for movement between places. Anything that is done that reduces the speed and efficiency of a road devalues that road. If we want to maximize the value of a road, we eliminate anything that reduces the speed and efficiency of travel.

The value of a street comes from its ability to support land use patterns that create capturable value. The street with the highest value is the one that creates the greatest amount of tax revenue with the least amount of public expense over multiple life cycles. If we want to maximize the value of a street, we design it in such a way that it supports an adjacent development pattern that is financially resilient, architecturally timeless and socially enduring.

These simple concepts are totally lost on us, especially those in the engineering profession. If you want to start to see the world with Strong Towns eyes and truly understand why our development approach is bankrupting us, just watch your speedometer. Anytime you are traveling between 30 and 50 miles per hour, you are basically in an area that is too slow to be efficient yet too fast to provide a framework for capturing a productive rate of return.

In the United States, we've built a 45 mile per hour world for ourselves. It is truly the worst of all possible approaches. Our neighborhoods are filled with STROADS (a street/road hybrid) that spread investment out horizontally, making it extremely difficult to capture the amount of value necessary for the public to sustain the transportation systems that serve them. Between our neighborhoods, towns and cities we have built STROADS that are encumbered with intersections, vehicles turning across traffic, merging cars and people taking routine local trips. These are not fast, safe and efficient corridors.

At best, the Diverging Diamond Interchange is putting lipstick on a pig. At worst, it is a continuation of our delusional fantasy that somehow we can sustain prosperity without building places of value. The Death Star pedestrian trench is despotic and demeaning. In the big picture, it is also an utterly meaningless waste of money.

We need to build places of value. We need to start building Strong Towns.

Understanding Roads

Americans are spending immense sums of money making cosmetic improvements to a transportation system that is simply not working. Traffic engineers, lacking the correct tools to actually solve traffic problems, have convinced themselves that they are fighting the good fight. They are supported by local government officials, anxious for that next hit of growth that will give the local economy a temporary high. It is a destructive alliance, one that we can no longer afford.

I don't want to pick on Springfield, MO. I have to admit that I've never been there, but I do like Missouri in general and have enjoyed my time there (except that summer at Fort Leonardwood -- yuck, I hate clay and chiggers). I'm sure Springfield is a great place filled with great people. They just have the poor fortune of having had a local booster make a ridiculous video touting the "pedestrian-friendly features" of their diverging diamond interchange and, well.... It's not personal, Springfield. We'd love to come there for a Curbside Chat.

Last week we looked again at the criticisms of my critique of the Diverging Diamond Interchange (DDI) in Springfield. In the piece (A 45 mph world - November 21, 2011) I made three observations:

- We don't have anywhere near the money necessary to maintain our current surface transportation system.

- The system we've built is financially inefficient and unproductive.

- Americans do not understand the difference between a road and a street.

Today we are going to look at the so-called roads feeding into the interchange. That would be Missouri 13, supposedly a highway of some sort. Missouri state statutes define a highway rather broadly in Section 300.010, actually indicating that a "street" is the same as a "highway":

"Street" or "highway", the entire width between the lines of every way publicly maintained when any part thereof is open to the uses of the public for purposes of vehicular travel. "State highway", a highway maintained by the state of Missouri as a part of the state highway system;

Maybe they mean that it could be a street OR a highway if it is publicly maintained and used for vehicular travel. It makes little difference, as we will see, because they've actually built neither a street nor a highway.

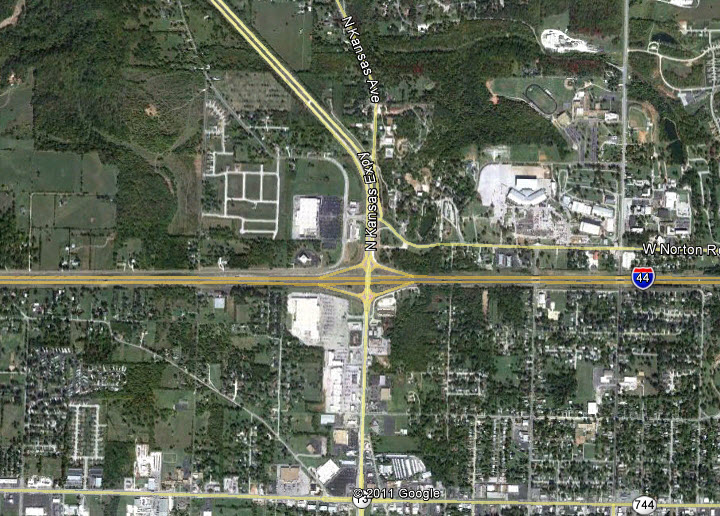

The photo below (credit: Google Earth) shows the diverging diamond and the surrounding land use. Notice that Missouri 13 (which runs north/south) intersects Missouri Route 744 about half a mile south of the diverging diamond. This is the short stretch of STROAD (street/road hybrid) we're going to focus on.

The Missouri DOT, using $3 million of state and federal funds, built the DDI. It was reported at the time that a regular interchange would have cost $10 million, making the DDI not only safer but much cheaper. This is the core of the argument in favor of the DDI, which I really don't disagree with. If you diagnose the problem here as one of traffic, then by all means, use the cheaper and safer alternative. And that is how they diagnosed the problem: "tremendous traffic problems".

Don Saiko, PE, who is a project manager in the Springfield, Missouri District of MODOT, got word of the DDI concept and wanted to investigate the design in the Springfield area. He got permission to test the design at I-44 and Kansas Expressway (SR 13) which had been experiencing tremendous traffic problems and safety issues due mainly to the small left turn storage areas to the ramps. A $10 million budget was given for the construction of this project. The simulations for the design looked very promising to fix the traffic and safety problems. It was also a very cost effective solution. The DDI was only going to cost about $3 million, saving the state $7 million of the budgeted cost, which would have been the cost for a conventional diamond solution.

If you only have a hammer, every problem becomes a nail, even if your hammer is a European import.

Unfortunately, like all DOT's that I have ever studied or interacted with, the problem in this situation was misdiagnosed. It was not traffic -- or more specifically the stacking and congestion of traffic -- at the interchange. The problem is how the public's investment in Missouri 13 has been debased for short-term economic gain and how, in the process, that has made the corridor unworkable as an actual highway.

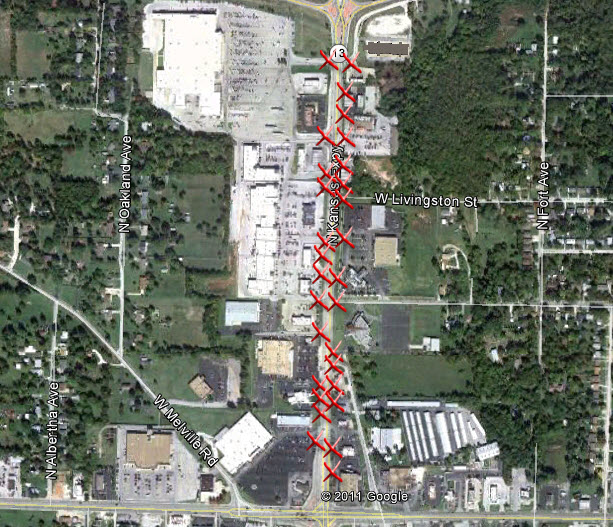

Here's what I'm talking about. In order to support the adjacent land use that you see in the picture above, that single half mile of Missouri 13 -- a state HIGHWAY -- contains 29 intersections (each marked with an 'X' in the photo below). That is an intersection roughly every 100 feet. You can't have a highway with smooth, free-flowing, efficient traffic patterns when you also try and accommodate that type of land use pattern.

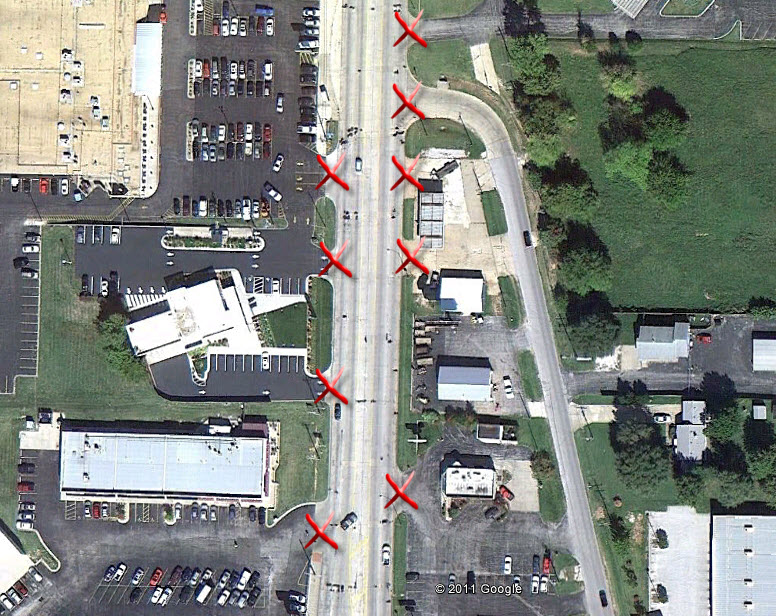

And look at some of these intersections up close. It is just plain bizarre, especially for a supposedly high-capacity roadway, one I'm certain we've invested millions of dollars to build and maintain.

Now ask yourself as you look at these photos: who are these engineers kidding? What type of improved traffic flow do they really think they are creating by spending $3 million up the street on an interchange? What type of safety improvements do they think they are making at an interchange when they have vastly more dangerous STROAD built like this?

Now ask yourself as you look at these photos: who are these engineers kidding? What type of improved traffic flow do they really think they are creating by spending $3 million up the street on an interchange? What type of safety improvements do they think they are making at an interchange when they have vastly more dangerous STROAD built like this?

This reminds me of the New Testament parable about looking at the sliver in your neighbor's eye while ignoring the beam in your own. Are we honestly looking at this corridor and diagnosing the traffic problem here as the interchange? Or is it just that the transportation funding -- not to mention the local land use incentives -- favor dealing with slivers and not beams?

This reminds me of the New Testament parable about looking at the sliver in your neighbor's eye while ignoring the beam in your own. Are we honestly looking at this corridor and diagnosing the traffic problem here as the interchange? Or is it just that the transportation funding -- not to mention the local land use incentives -- favor dealing with slivers and not beams?

And this is just one half mile. This pattern extends a long ways along ol' Missouri 13.

This is far from an efficient transportation system. If you give me $10 million to spend here, I spend it closing accesses. You can do more to improve traffic flow and efficiency by closing these accesses than anything else. All you have here is a bunch of people making inefficient local trips on a highway sized for high-speed, through traffic. That's not a traffic problem. It's a land use problem.

Of course, we can't close accesses. People who own land adjacent to highways have a God-given right to highway access, regardless of the impact. And when an access is taken away, they must be compensated (although it should be noted, when the highway was built, is improved and/or their access is enhanced, that is just the public's responsibility and by no means should be a cost assessed to them). It is the local land use version of "heads I win, tails you lose" because -- in our current system -- the public is either forced to invest endlessly in a transportation approach that can never truly work or are going to pay huge sums of money in compensation.

If those are the only two choices we have, I refuse to play the game. I would not spend a dime on this waste of a corridor. As I wrote last week, the DDI is just putting lipstick on a pig. (Note: Later this week I am going to discuss some other choices we might consider, things that are not on the table today).

Let me finish by making two related observations. The major impetus for building the DDI here was supposedly safety, as it supposedly is in all similar transportation "enhancements" (see earlier conversation on slivers and beams). In fact I had to laugh at this AAA spokesman who has bought into this racket as well:

Mike Right, spokesman for AAA Missouri, said the new design is a positive change, as it reduces construction costs while moving traffic faster and more safely. As motorists have adjusted to roundabouts, American drivers will learn and adapt to the diverging diamond, he said.

I'm assuming that he drove the Missouri 13 STROAD -- about the least safe traffic environment you could be in, with high-speed designs mashed up with turning traffic, stop and go traffic, sudden lane changes and obnoxious signage -- thinking that this was normal. And it is, really, because despite being ridiculously unsafe, it is a design that is ubiquitous across America.

Which leads me to my other observation: Is this all worth it? Yeah, you got the WalMart investment there (which yields less in tax capacity on a square foot basis than Springfield's traditional neighborhoods, I am certain), but really, does anyone in Springfield believe this is more than a near-term benefit? If you do think this is a great long-term investment, I have a challenge for you. Drive south along Missouri 13 until you find the area that was built 30 years ago. How's that area looking? How's it holding up?

I'm going to venture an educated guess that it's not. Like the land use around the DDI intersection, it was designed for one life cycle. It will not retain its value, it will not be adequately maintained. Today's next new thing is tomorrow's place in decline and a future slum or brownfield site. For some reason we accept that in America. We need to step back and realize that, in the course of human history, it is not normal. Or healthy. Or financially viable.

The time to start building Strong Towns is now.

What now, Chuck?

People are always looking for simple solutions. I'm routinely asked at Curbside Chats to give the one or two things that should be done to fix our current economic problems. Those things don't exist, because if there were a painless, simple way to solve our problems, we certainly would have done it. In fact, part of the reason we are here today is that we've done the simple and painless thing for so long (see Growth Ponzi Scheme series). Today I present a couple of more difficult, but long-term more effective, options.

One of the comments from last Tuesday expressed the common frustration with my analysis of the Springfield, MO, diverging diamond investment and the surrounding land use pattern:

I agree 100% that this area is poorly designed, pedestrian-hostile, and dangerous; that Walmart is a cancer on the economy and on society; and that were we to start from scratch this outcome ought to be considered a monstrous failure. But here in the real world, we have a busy and dangerous street, a bottleneck overpass to an area where a lot of commuters live, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of existing infrastructure in place. Do you leave the area to rot? If not, how do you improve it?

Ah, the "real world". I respect the point, of course, but also get frustrated by the limitations we put on ourselves. So much of our dysfunction is simple inertia. Changing our approach is so difficult. We know, for instance, that something like Medicare spending is unsustainable, but we also realize that collectively we are unlikely to do anything substantive to deal with the problem until we're actually in a crisis. Some of that is human nature. Some of it is the variant of democracy that we have evolved into. Either way, I'm going to go back to the original post in this series and remind our readers today of the three critical insights.

- We don't have anywhere near the money necessary to maintain our current surface transportation system.

- The system we've built is financially inefficient and unproductive.

- Americans do not understand the difference between a road and a street.

On the first point specifically, the crisis is coming. It is actually already here, but we've been using debt to avoid facing it. We don't have nearly enough money to maintain all of the systems we've built. (Note that you can argue that we do have the money, and technically you would be right, but it is the same as arguing that someone should be able to pay their $2,000 monthly mortgage on an annual salary of $30,000. Technically they could, but in the real world, they can't.) Because we don't have the money, and because each increment of investment in the current system makes us financially weaker over the long-term, our approach is going to force a crisis. In short, at some point very soon we're going to look at the "real world" in a very different way (and, if you keep reading this blog, you might actually see the "real world" -- that is, the world as it really is -- much sooner).

Here are two simple ideas of mine that would effectively deal with the STROAD (street/road hybrid) problem within a generation. While these may seem politically impossible today (and that is why I emphasize that they are solely my ideas), I offer two points of support up front. First, we are nowhere near being able to afford to maintain our transportation system and thus we are ultimately going to be forced to make choices that, as viewed today, seem politically impossible.

Second, when you view our current transportation system with clear eyes, you can see that it is an incoherent approach. Dabbling around the edges, like so many of our transportation initiatives do, is simply conversing with incoherence. The result: incoherence.

Idea #1: End the State Aid System

Each state has their own version of a state aid program. I'll focus on Minnesota's with the informed belief that other states are similar in their approach.

The Minnesota non-profit Fresh Energy explains how money is allocated between the highway system and the local state aid system.

Dedicated state funding (the money that comes from the gas tax, tab fees, and the motor vehicle sales tax) is allocated by formula through something called the Highway User Tax Distribution Fund. The State Trunk Highway Fund receives 62 percent to build and maintain Mn/DOT highways, the County State Aid Fund receives 29 percent to pay for county roads, the Municipal State Aid Fund gets 9 percent to take care of roads in cities, and 5 percent is set aside for purposes determined by the Legislature. Most of the federal money comes through formulas as well, while it is predominately targeted toward the state highway system. Between 2004 and 2008, an average of 84 percent of federal money went to the state highways while cities, counties, and towns received 16 percent.

In short, large sums of money are collected at the state and federal levels for transportation and then a portion of that money is transferred back to local governments for transportation. Along with the money comes requirements that dictate how that money is to be used. These include engineering requirements for things such as lane width, degree of road curvature and design speed and planning requirements for things like maintaining a hierarchical road network. (Knowing this can actually make you a touch sympathetic, on a personal level, to the ridiculous engineer bear.)

In the "real world", the state aid system is the primary funding mechanism for the worst design practices at the local level. Most STROADS are built using this funding. Financially, these are the least productive of all transportation investments, spending enormous sums of money to speed up purely local trips by nominal amounts of time, often right through the middle of neighborhoods, lowering the value of the place in the process.

Let me provide three local examples so you can start to see these places in your community (they are everywhere).

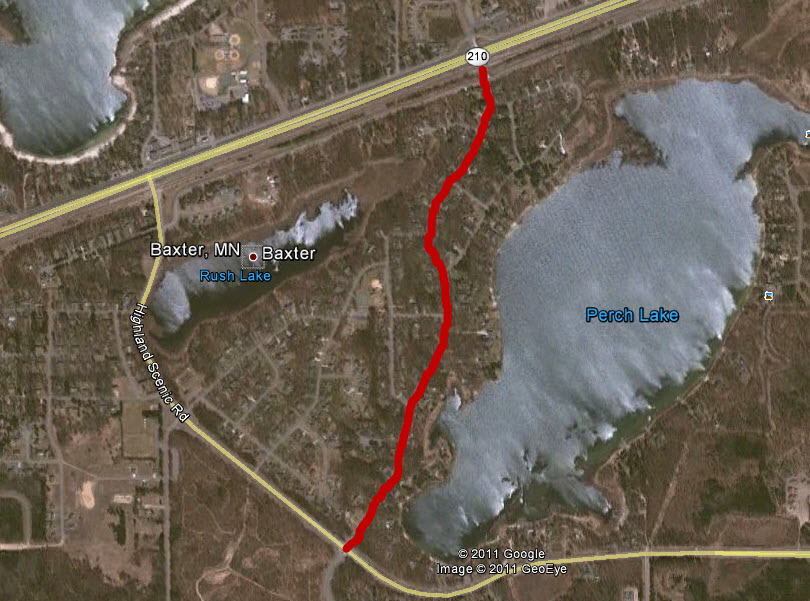

(1) When I was a kid riding the bus we used to travel down Knollwood Drive in Baxter. It was a local street that ran through a post-WW II subdivision, with lake-fronting properties on one side and off-lake on the other, curving streets and a lot of cul-de-sacs. This was an early suburban-era design -- I would guess 1960's -- and so, even in my youth, the infrastructure was showing its age. It was a bumpy bus ride.

Sometime in the mid-1990's, the city of Baxter reached population levels where they qualified for state aid. State aid rules require the designation of state aid routes, corridors that begin and end on state highways or other state-funded corridors. Knollwood fit the bill, and so a convenient remedy to repair the failing infrastructure along Knollwood was to designate it a state aid route.

Of course the residents did not like this one bit. This was a small neighborhood, not a major transportation corridor. But as the project proceeded and was combined with sewer and water extensions as well as other "improvements", the price tag climbed to levels where accepting the state aid designation, along with the significant money, was the lesser of two evils.

In the photo below I've highlighted Knollwood in red. You can clearly see that it serves no significant purpose in terms of regional transportation. At best it is a shortcut through a otherwise-sleepy neighborhood, allowing someone to save a few seconds or a minute on getting from one place to another.

(2) The city of East Gull Lake has a small dam that serves as the crossing of the Gull River. It is a single lane crossing and so you have to stop on each end and then yield to oncoming traffic. It is actually kind of charming and, particularly in the middle of a campground/recreation area, does a lot to calm traffic.

(2) The city of East Gull Lake has a small dam that serves as the crossing of the Gull River. It is a single lane crossing and so you have to stop on each end and then yield to oncoming traffic. It is actually kind of charming and, particularly in the middle of a campground/recreation area, does a lot to calm traffic.

Unfortunately, the approach to the damn from the west is a county state aid road (CSAH 70) while the approach from the east is a simple county road (CR 125), a road not supported with state aid money. The catch here is that CR 125 was decrepit and in need of maintenance. The cost was (and the exact figures allude me so I'm going on memory) somewhere around $1.2 million. Because CR 125 was not a state aid route, it would be entirely the county's bill.

So they could access state aid money -- along with some other federal grant money -- for this project, the county came up with a plan to connect CSAH 70 with CR 125 with a new bridge across the Gull River. The cost for this project would have been in the many millions of dollars for a new bridge, the widening and realignment of CR 125, the condemnation of a couple of homes, etc... The catch is that the local portion of the project -- the county's share -- would have been only around $600,000 and they could have used state aid money for it.

In retrospect this looks even more ridiculous because, while the bridge project didn't happen and nothing remotely calamitous has transpired from a traffic standpoint since, the public was told at the time that tremendous traffic projections along with safety enhancements made this project a necessity. That was utterly ridiculous. It was simply the ability to access outside funds that pushed the design of the project, not local traffic concerns.

(3) Our local heartbreak project in Brainerd is our Last Great Old Economy project, College Drive. I've written extensively about this project in the past because it is a perfect example of the destruction wrought by the state aid system. Poor neighborhood in decline on one side, local community college on the other side. Instead of building a sensible project that would connect the two and strengthen each (local cost around $1.2 million), we instead leverage our next four years' worth of state aid dollars, along with other federal "stimulus" money, to build a $9 million, 4-lane STROAD. (Ahh, but it's a "complete street" says the engineer). Local cost for the STROAD is less than $1 million.

The state aid system actually makes it cheaper for the city to build a destructive corridor -- one whose central outcome will be to allow the people of South Brainerd to reach the Walmart in Baxer 45 seconds more quickly -- than to build a neighborhood-affirming corridor, one that would capitalize on all of the existing investments made by the city and its residents in this area.

Ending the state aid system -- eliminating the funding of local auto-based transportation along with the planning and design mandates that accompany it -- would effectively end the destructive practice of building terrible local transportation corridors, and it would end it within a generation. As soon as these corridors became decrepit, local values and sensibilities would demand that their replacement respond to the community, not outside design criteria.

Note that I am not arguing that the there should be no role for the state in funding local transportation. That is a completely different discussion. All I'm arguing is that the state aid system is broken, should not be "reformed" but should simply go away.

Idea #2: Institute an Accessibility Tax

There is talk about funding transportation improvements through an increase in the gas tax, a mileage tax, tolls roads, increased allocations of general fund revenues, etc... Each of these has upsides and downsides, but all of them do nothing to address the fundamental lack of productivity inherent in the current system. They would all simply be new revenue streams that would reinforce the unsustainable status quo for a little while longer.

As I discussed Tuesday, one of the problems we run up against in building roads is that it is really difficult to close accesses. There are all kinds of constitutional issues around takings that make it very difficult and costly. I don't want to have that argument -- heads you win, tails I lose -- regarding the cost and benefits of improving a transportation corridor when you don't have any control over the access. Let's allow as much access as property owners desire, but let's charge for it.

There are no constitutional issues for a state when it comes to taxing or tolling on roads. We should institute an access tax (or toll) that would be designed to, in a sense, compensate the public for the decrease in capacity caused by the access. It would work something like this.

On a rural country road where you have 1,000 cars a day, putting in an access is no big deal. You have a driveway that goes out to the highway and it is no problem to wait for the car that may be happening to drive by when you pull out. Your driveway, and the turning movements it creates, does not inhibit the flow of traffic on that corridor in any way. Your tax would be very low, perhaps $20 per year.

On a very busy highway, something with say 20,000 cars per day, Walmart would like to build a new store. They want a traffic signal and a 3/4 interchange on the north and south ends of their property, respectively. Okay, we know from the math used to justify highway projects how much cost adding those accesses would create for the public. It is the opposite of the "benefit" improved mobility would create. Here's how the math would work.

Let's say the new signal and intersection delayed the average car by one minute. At 20,000 cars per day, one minute each, in a year you have a total delay of 122,000 hours. If we hold to the belief expressed in so many reports justifying highway expansions that this time should be valued at (on the low end) $13.40 per hour, then that signal has a cost to society of $1.6 million per year.

If Walmart wants that signal -- if the local unit of government wants that access -- than there should be a tax/toll/charge of $1.6 million per year to compensate the public for the time lost and the reduction in capacity. That money could be used to enhance the system and restore a comparable amount of mobility elsewhere. I'm not sure who pays it -- the businesses, the drivers or the local unit of government -- but there should be some mechanism for compensation.

(Note that I am proposing this for highways only, not for local streets, the latter of which we need to encourage more access to.)

Such an access tax would not only raise revenue that could be used to improve mobility, it would have two other immediate impacts. First, property owners eager to avoid the access tax would immediately and voluntarily start closing accesses along major highway corridors. Not only would this improve traffic flow and mobility, it would dramatical improve safety.

Second, and most important, it would actually restore the local property market to something based on place and not something based on government transportation decisions. Decisions on land use would again be local. With local decision-making, where the financial costs and benefits are also local, there would be strong incentives to, once again, start building places of value. We would immediately get away from the too-big-to-fail mega subdivisions on the edge of town and again start incrementally wringing value out of our places, block by block, neighborhood by neighborhood.

Where an additional access to the highway was needed, there would be every incentive to maximize the value capture from that access. You wouldn't have a traffic signal that you have to sit at where there is simply a gas station, a donut shop and some storage sheds. That type of land use would not be viable (not because of the tax but because it actually is not viable without the enormous transportation subsidy). Our highways could not only function as highways again (fast, efficient connections between places), but our places would start to redefine themselves along a financially-sustainable pattern. They would have to or they would fail.

Now there's the catch, and so I'm not pretending this proposal would be easy to get passed or easy to implement. It would, by ending the perverse transportation subsidy we've created, expose all of the poorly- and inefficiently- configured spaces that we have made in the post-WW II era. That would be extremely painful for many communities. Some would be able, over a generation, to reconfigure themselves in a more viable way. Others would not. Some community triage and support would certainly need to take place. I'm not pretending that I've either the answer for that or have even thought it through enough to suggest how it would happen. A later post, perhaps.

I'll go back to where I started: we don't have the money to maintain everything we've built. Continuing with the status quo approach will only make that problem worse in the long run. We can tinker around the edges with new state aid standards, new federal and state mandates, new taxes and fees, but unless we do something to deal with the core problem -- the financially unproductive nature of the post- WW II land development pattern -- it will not solve the problem.

These two proposals, as difficult as they are to imagine enacting today, would address the real problems we have and do so in a substantive way. While they would certainly create other problems and harships, doing so is a necessity for getting our places healthy. We need to think in terms of generations, not months. Phasing in these two approaches over the next few years would set the stage for a renewed Strong Towns discussion in each and every community in America.

And that is something that desperately needs to happen.

Strong Towns is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support this blog and our other efforts to build a stronger, more resilient America. And if you want to learn more about implementing a Strong Towns approach in your community, join the Strong Towns Network. We'll help you make it happen.