Commodity Traps: The Road to Poverty

Chris Gibbons, former Director of Business/Industry Affairs in Littleton, Colorado, is a pioneer in Economic Gardening. We previously interviewed Chris for a podcast where he explained Economic Gardening and how it is being done in cities across the country. The following is an excerpt from an upcoming book on the same topic.

---

Like the beating heart of the live organism it is, economies expand and contract wealth creation through cycles of innovation and commoditization. We can visualize bringing new products to market as a bell curve. On the left hand side rising side, the creation of a successful new product also creates a new company, new jobs and new wealth. Profit margins are high, the economy improves and most everyone benefits.

At the top of the curve, the market saturates, the competitors catch up, commoditization sets in and a shakeout begins. On the right hand falling side, the higher priced products lose out, those companies fold and their jobs and wealth disappear. The remaining wealth becomes consolidated in a few companies and then in the hands of the owners as commodity pressures force down wages for those with unfavorable supply/demand ratios.

Communities caught in commodity traps drift toward the Latin America model of a small wealthy elite living behind walls high on the hill with poverty spilling down through the massive favelas and slums below. On the other hand, communities that continually innovate pump new wealth into their economic system and end up with a healthy middle class.

Let’s explore both paths, starting with the commodity trap. Here is an eternal truth: If there is more supply than demand and you can’t differentiate, you will be poor. You cannot get away from that fact in a free market economy. Take this simple example to understand why this is true.

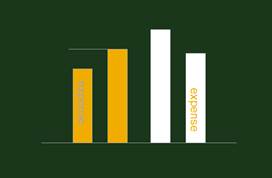

If you and I are competitors and we sell exactly the same product (think of salt; no matter how you package it, it is NaCl –sodium chloride). In the diagram I sell salt for $2.00 a pound and that creates my income bar. I can produce it for $1.90 a pound which creates my expense bar. The gap between the two is my profit: $.10 pound.

You, on the other hand, have your salt priced at $1.80 a pound (your income bar) and can produce it for $1.70 a pound because you have more efficient systems, buy in bigger quantities, pay your employees less and a myriad other reasons—all of which lead to the fact that your unit expenses are cheaper than mine.

The customer looks at our two companies and see’s salt for sale – at $2.00 at my business and $1.80 at your business. It is exactly the same: sodium chloride and nothing else. It’s a short discussion in his mind: “I’ll take the less expensive one, thank you very much.”

I figure this out pretty quickly and soon I drop my prices to $1.60 per pound, twenty cents cheaper than yours. But my expenses are still at $1.90 and so I work to get those down. I put in even more efficient systems, buy in even bigger quantities, pay my people even less and negotiate my lease rate down. Customers flock to my salt store.

You now have the problem that I had yesterday in that your prices are too high because your expense are too high. You are forced to do what I did and that is get your costs down even further so that you can drop your prices below mine (say $1.40 a pound). Once you do, the customer streams diverts from me back to you.

And then I lower my expenses and drop my prices again followed by you dropping your prices and lowering your expenses. You can see what is happening: we are in a race to the bottom. We are both caught in a downward spiral that neither one of us wants to be in but neither can get out of it. It’s like an arms race: neither side wants to do it but neither side can afford to stop.

This, then, is the core problem with commodities regardless of whether it applies to your job, your product, your company, your community or your nation. If you cannot differentiate, you have to compete on price alone and that pressure forces a reduction in costs. Depending upon which side you are viewing from, the system is either making us be more efficient and reducing the price of things (the WalMart effect) or it is driving down profit margins and wages making us poorer. Both are true.

Good people – people who work hard, play by the rules, who take responsibility for their lives-- get caught in commodity traps and end up poor. There is only one way out.

When the book, which is still being written, it published, we will make every attempt to have Chris back on the podcast to give us an update. In the meantime, here are some important links on this subject:

- The Edward Lowe Foundation's Economic Gardening site

- Chris Gibbons on Twitter and LinkedIn

- Economic Gardening Google Group (news and updates)

- Email Jessica Nelson at the Lowe Foundation

- Email Chris Gibbons for more information