Putting our Towns on the Path Toward Good Public Transit

I love transit. I ride the bus frequently in my current city and have relied completely on public transit in past cities where I’ve lived: New York City and Washington, DC. If we’re talking about my personal feelings towards transit, I would love to see much of the current transportation dollars we spend on roads diverted towards transit spending.

“There are fiscally responsible ways to build transit systems and there are many incredible transit systems flourishing in cities across the continent. But there are also pitfalls to be avoided here.”

But I cannot remove my Strong Towns, fiscally-responsible hat when I look at transit projects. If we’re going to be critical of road projects that spend billions in taxpayer dollars, we have to also be critical of transit projects that do the same. There are fiscally responsible ways to build transit systems and there are many incredible transit systems flourishing in cities across the continent. But there are also pitfalls to be avoided here.

Today, I want to discuss a few of the common arguments that I often hear about public transit in the context of the Strong Towns movement, including arguments that every town needs transit, that incrementally growing a transit system is impossible, and that large rail projects are the best way to get more people using public transit.

Scaling Transit

When I hear Strong Towns readers saying “You guys don’t do a good job of talking about transit,” (which has happened a couple times in the last few weeks, especially in light of our recent conversation on housing affordability in Portland) I wonder if what they really mean is, “You guys don’t do a good job of affirming my personal belief that we need more transit everywhere and advocating for large increases in transit spending.”

At Strong Towns, we have an audience that lives in everything from the smallest rural towns to medium-sized cities and suburbs to some of the biggest cities in the world. We aren’t going to tell New York City how to run its transit system—they seem to be doing a pretty good job and that’s a local issue anyway. But we also aren’t going to tell a rural township that it needs a bus rapid transit system when none of its residents have ever ridden a bus.

Most cities are somewhere along that spectrum—they’ve got some sort of bus system that is likely largely ridden by low-income, elderly and disabled residents, and maybe they’ve got light rail or bus rapid transit plans in the works. These communities can improve their transit systems with an incremental approach and the right cultural mindset. Without it, they are at risk of wasting billions.

An Incremental Approach to Transit?

I know several commenters on this site have argued that an incremental approach to transit isn’t possible, but I disagree.

When we talk about a Strong Towns approach to transit, we have to think about incremental ways to improve these existing systems. Maybe that means rethinking the routes and frequencies to serve more people in a better way, like Houston did (with help from a Strong Towns member). Maybe it means converting to Bus Rapid Transit along key lines, like Fort Collins, CO did. Maybe it means one day turning some of those bus routes into permanent light rail lines.

If you’re in a very small town, then maybe the first transit step you can take—if that’s a transportation option your community desires—is investing in some large vans, figuring out which populations would be most likely to use them and charting a route that takes those people where they need to go. (That’s how I got around in my college town of Walla Walla, WA.) Or maybe, if your town is truly tiny and rural, there is no place or need for transit anyway because driving, biking and walking fit best with the existing infrastructure and preferences of your neighbors.

Image from The Pointer, 1972

Small-scale, incrementally-grown transit can work. My fiance’s grandparents started a homegrown, small-scale transit system in the town of Stevens Point, WI back in the '70s. When the town’s previous bus system failed, Roland Thurmaier (my fiance’s grandfather) formed a coop of community members who agreed to pay into the bus system at the rate of $5 a share. The system started with $900 in 1972 (about $5,200 in today’s dollars).

They realized immediately that they could not maintain the extended system that the local government had originally attempted to build. Instead, they pared down the routes to connect residents with key shopping areas. An article in 1972 published in The Pointer (the local university student newspaper in Stevens Point), quotes Thurmaier as saying that 15-20% of the residents in the town don’t own cars. Many of those were (and are) students because the University of Wisconsin has a campus in Stevens Point. Thurmaier explains in an interview in the article:

The car is one of the extravagant users of our natural resources and, in fact, the people who do not own cars are subsidizing those who own cars; because those people, either through rent or direct property tax, are paying for the elaborate street system we have, wages for traffic patrolmen, and that kind of thing.

A man before his time. Those words are as true today as they were in 1972, and we know that wages for traffic patrolmen are just one of many expenses (paving, barriers, signals, etc.) that our extended American road system incurs. From $900, with volunteer bus drivers and in the beginning, just one old school bus, a cooperative of Stevens Point residents built a workable bus system that fit their communities’ needs and its budget. Over time, they added to their fleet, moved their office out of the Thurmaier family home, sold advertising to raise additional revenue, adjusted routes based on need, and hosted free-ride days to increase their visibility. In 1979, the city took over the bus system. It has grown incrementally over time and is successfully operating to this day.

A Cultural Shift

We desperately need a cultural shift if we’re going to make transit a useful and worthwhile investment for our cities and towns. I live in the mid-sized city of Milwaukee in a middle class, densely-populated neighborhood full of mostly childless young people and seniors. Using my city’s subpar bus system, I can still get to many of the places I want to go because I am located close to the downtown, which is the heart of our hub-and-spoke bus network.

Despite this excellent location, relative affordability of our bus system ($1.75 per ride with an M-card), relative challenge of parking in our dense neighborhood and prime demographics for easy transit use, many of my nearby friends have never and will never take the bus. Even when they’re going to an event where parking will be a huge headache and expense. Even when they’re planning to be drinking. Even when there is a bus stop literally in front of their homes. Because they are part of the middle class, and probably grew up in towns where bus use was uncommon and reserved for the poor, they do not even consider riding the bus. That’s for someone else to do.

Understand that I live in an urban neighborhood in the heart of a city that is warming to things like bike lanes, mixed-use developments, and walkability—all the hallmarks of a modern, urbanist lifestyle. My friends visit breweries, live in apartments, shop local—all the stereotypical urban millennial stuff you’d expect. And yet they won’t ride the bus. Car is king, as my alderman once phrased it.

Blue line indicates the initial route of the new streetcar. (Image from TheMilwaukeeStreetcar.org. Click to view larger.)

In my town, a new streetcar line is in the works that will make a two-mile loop around the downtown. It will cost $128 million to build (a good chunk of it, outside money, of course) and will probably be used mostly by tourists or downtown office workers getting lunch or doing shopping after work. It’s not really helping people to commute because the distance it covers is so small that you could easily walk or bike it, and this neighborhood is already thoroughly served by bus routes anyway.

The goal is that this line will be a starting point for other routes to expand out from. I’m hopeful that that’s the case, but maintaining a healthy skepticism, especially since the city has yet to break ground on the initial line.

I was recently chatting with a friend who works at the regional headquarters of a bank in a downtown office building with a parking ramp. It costs a good deal of money to park in the ramp every day and it’s about a 20 minute walk from his apartment, so most days, he chooses to walk or take the bus to work. He has a car, but he makes this choice because it’s economically beneficial to him (not to mention safer, healthier and less stressful than driving in rush hour traffic).

However, he commented that the vast majority of his coworkers pay for parking in the ramp every day, including the ones who live within easy busing distance because, as my friend put it, “If you’re making six figures as a bank manager, you’re not going to take the bus.”

This is what we’re up against if we want to promote increased transit options in our cities.

A Case of Priorities

Many transit advocates state that rail is the best way to get more people using public transit because it’s a more appealing option for middle and upper class people, compared with the bus. I know there’s survey data to back up that statement, but I still don’t think that justifies the immense expense of rail in many cases.

I honestly don’t understand why there is a mythical love of rail over buses. Perhaps it’s because people associate rail travel with beautiful European cities, Harry Potter or historic America? Or maybe the preference of rail over buses is because people perceive rail to be quicker than buses? That may be true with subway systems and is sometimes the case with separated light rail, but it’s not often the case with streetcars (unless other street improvements are made simultaneously, as Jarrett Walker points out, and that could happen with bus lines too). And most American cities are not considering subway lines when they talk about building rail anyway.

Jarrett Walker, transportation planner and writer at HumanTransit.org has a very wise perspective on this issue:

We are living in a time of epochal changes in the culture of transportation, increasingly forced upon us by a changing calculus about what works and what we can afford. I have seen monumental changes of attitude in the nearly three decades that I have watched these issues. For that reason, I instinctively give more weight to values that have proven themselves stable over centuries — such as the need to save travel time and money — than to the negative associations that may have gathered around buses, in some cities but not others, just in the last half-century. When people face a stark choice between retaining their prejudices or saving time/money, prejudices can change pretty fast.

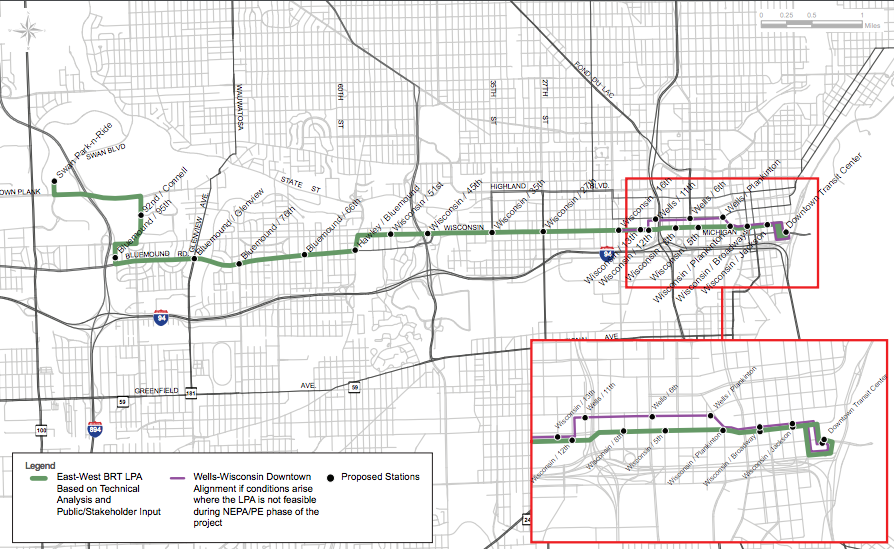

Image from EastWestBRT.com

In addition to the streetcar in the works in my city of Milwaukee, there’s also a Bus Rapid Transit line proposed to run East-West through the middle of the city. This 7-mile route would connect the western half of the city and western suburbs with downtown jobs, as well as connecting urban residents with jobs in the western suburbs. The 2-mile streetcar project is estimated to cost $128 million while the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line is estimated to cost between $41.9 million to $47.9 million. The corridor that the BRT line plans to service is heavily congested and heavily traveled during rush hour. The inner-city neighborhood it would reach is one of the poorest in Milwaukee.

If I was in charge of funding decisions in this city, I’d build 3 BRT lines (East-West, North-South and Downtown-Northwest) before I’d give the streetcar project a second glance. And, if these cost estimates are similar across the board, we could do all of that for only $7 million more than the entire streetcar project. We could serve tens of thousands of Milwaukeeans of varying incomes with that kind of investment, and we could adapt that route as the population and job centers changed over time. In my opinion, if there’s public transit money to be spent in a midsize city like mine, busing and BRT are a far more worthwhile investment than rail.

In sum, I don’t think our cities should be making massive rail investments merely because they think it will encourage wealthy people to finally give public transit a shot. I’d rather focus time, effort and even money on changing the culture around busing and adjusting bus routes for increasing ridership—proving that is can save people time, money and stress— and eventually transitioning to Bus Rapid Transit where appropriate. (Making public transit safer for women should also be a priority.) In some cities, rail is ideal and the community is ready for that investment, but in many like mine, I think it's too risky.

On the article that spurred this whole conversation, Strong Towns' guest writer and member, Alexander Dukes offered an insightful comment on public transit hesitance:

“People think highways are absolutely necessary because they know nothing else. People think transit is only for the poor because they’ve never seen people that aren’t poor ride it.”

I think you have to give people time to overcome their ignorance. People think highways are absolutely necessary because they know nothing else. People think transit is only for the poor because they've never seen people that aren't poor ride it (and because it requires them to surrender their autonomy and use the prescribed routes- something automation will solve I think). We know all of these things work together to make a place work well — it takes time for the public at large to understand that.

I’ll give non-transit users even more credit: If we want transit to be highly successful and financially sustainable, we need a critical mass of users. In many towns, cities and suburbs, that means we’re going to need people who drive a car several times a day, every day, everywhere, to relocate at least some of those trips to a bus. That’s going to be a real challenge.

It’s like asking someone who has eaten meat every day for their whole life—and who believes that meat is the easiest to prepare and most delicious food—to have a few meatless meals each week. It’s not impossible, especially since we’re not asking them to become a full-fledged vegetarian, but it’s going to take some easing in, and showing them that there are plenty of tasty meatless meals, and offering ideas for what to cook and proving that those meals will fill them up just as well as a pork chop could. In the end, they’ll hopefully realize that vegetarian meals are often cheaper and healthier, but it’s a huge mindset shift.

To take the metaphor even further, a person who is resistant to changing their diet in this manner might eventually have a wake up call—like a heart attack—after which the doctor says, “If you want to live, you need to stop eating so much meat.” In the same way, many of us find ourselves using transit (or biking or walking) because we simply cannot afford the expense of a car. Growing up, my family used a car to get basically everywhere and when I started driving as a teenager, I would borrow my parents’ car. But when I attended college and after I graduated, there was no way I could afford my own car, so I went without. I figured out other transportation options.

This experience of losing the option to drive—whether because of a loss in income, an injury, aging, etc.—forces people to find other modes of transportation. As the cost of living and cost of gas rise while wages and wealth stagnate, more and more Americans will find themselves needing to drive less or give up their cars altogether. And when they encounter that situation, I'm going to guess that they'll be willing to use whatever transportation options are available to them. It's not going to matter whether that vehicle looks like a sleek new train or a ten-year-old bus, they—like me—will take whatever will get them where they need to go in a safe, affordable and timely manner.

“If we say that only a massive transit system has any hope of making an impact on a city, then we need to very critically assess how much money we are willing to invest in that gamble, how much the system will be used and how much payoff we can be guaranteed to receive.”

IS BIG THE ONLY WAY?

If we say that only a massive transit system has any hope of making an impact on a city (something I've heard several times), then we need to very critically assess how much money we are willing to invest in that gamble, how much the system will be used and how much payoff we can be guaranteed to receive.

Personally, I think that premise is absurd. Do I wish my city had a more expansive transit network and more frequent service? Absolutely. Do I think that our existing bus system has no value for the people of Milwaukee? I believe the 142,000 average bus trips daily in my city (41% of which are to or from employment) speak for themselves. I believe the tens of thousands of Milwaukeeans who don’t own cars (including me) and rely solely on busing and walking for their transportation are making very good use of our bus system. And they deserve a better one.

So, yes we need more and better transit. But we cannot be blind to the financial risks that expensive transit systems—especially completely new ones—create. Before we invest in them, we have to look at them with the same critical eye with which we view expensive road projects:

- Will this investment make my town better?

- Will we be able to pay for the maintenance of this project 10, 30, 50 years down the road?

- Does this project depend on build-it-and-they-will-come assumptions to work financially

- Will this create value for my town today and for future decades?

- Can we afford this project?

- Is this the best use of limited resources?

What’s the goal?

When thinking about transit (or any other investment in our cities), we have to ask ourselves what the ultimate goal is. For some Strong Towns readers, I think the goal is simply: Get more people riding transit. If that’s the case, then we may not see eye to eye in transit conversations, because many transit advocates coming from that perspective will choose to build the most attractive, fastest and biggest project possible, right?

But if the goal is:

- Build more financially sustainable cities, or

- Create cities that are affordable for everyone who lives in them, or

- Develop a transit system that meets the needs of all residents, or

- Plan for the future of our cities in a realistic and affordable manner

then we are having a different sort of conversation, and I think we will find a lot in common. We all want cities where residents of different incomes, ages and abilities can safely and easily get where they need to go. We all want cities that are financially resilient and aren’t putting future generations in debt. We can achieve these goals with public transit as part of our transportation network and we should.

We just need to go about it in with an incremental, financially-aware and realistic mindset.

(Top photo by Johnny Sanphillippo)

Mike Christensen is the executive director of the Utah Rail Passenger Association. Today, he joins Tiffany to discuss the benefits of passenger rail, including how it can lead to more productive land use. (Transcript included.)