10 Rules for Cities Thinking about Automated Vehicles

Jeff Speck is a city planner, urban designer, and author who, through writing, lectures, and built work, advocates internationally for more walkable cities. This article is based on a talk the author gave to the US Conference of Mayors and CNU, and is republished with permission from CNU: Public Square.

Traditional urbanism evolved over millennia to meet human needs. The adoption of autonomous vehicles (AVs) should not be allowed to replace time-tested places with something that would probably make our lives worse. For cities considering the future of AVs, here are ten things to keep in mind:

1) Be afraid.

One of my favorite books of all times is Technopoly, The Surrender of Culture to Technology, by Neil Postman. In it Postman describes what he calls the technological imperative. What it means to me is this: New technologies that increase convenience are unstoppable, whatever their impact on our long-term quality of life.

It happened with cars—enthusiastic adoption followed by some dubious outcomes. This includes: The doubling of the percentage of incomes spent on transportation; We travel no faster in cities than we used to with the horse and buggy; The impending drowning of our coastal cities, now occasional and eventually permanent; The transformation of so much of the American public realm into an unmitigated soul-sucking eyesore; The mortification of our bodies through inactivity brought on by the elimination of the useful walk; The loss at last count of 40,000 American lives each year.

None of this was planned, the technology won, and it will win again.

This last item represents the key argument for automated vehicles (AVs). If adopted en masse, they will save hundreds of thousands of lives—so many that the organ transplant industry is worried. Additionally, we can expect that a lot of urban land will be available for other uses because we will not need so much parking. That seems to have no downside, but, as I will try to show, these two positives can be offset very quickly if we are not careful.

Promotional image from Ford

2) Be realistic (or, What to expect, when you are expecting AVs).

It reminds us that major change is unlikely to happen for several decades. Notice even the image (on the right) which Ford uses to promote its vision, refers to decades and decades from now.

Other experts think that full autonomy will not happen at all. And that's a problem, because most of the benefits of AVs really only kick in when we have full autonomy—a swarming fleet of shared vehicles that operates as a public good. This challenge is well described by Robin Chase, the founder of Zipcar, who describes AVs as a heaven or hell scenario.

Heaven is fleets of shared electric driverless cars powered by renewable energy, and a more socialist—my word—wealth distribution system to help all of the drivers put out of work by driverless cars.

Hell, on the other hand, is privately owned AVs, that, since they have nowhere to park, spend much of the day circling, doubling the traffic load. In America, we have shown zero propensity to control how people buy or use their cars. European cities like Barcelona might create large car-free zones or close two-thirds of their streets to through traffic. Not even New York City was able to pull off something as minor as congestion-based toll pricing. Without regulation, the heaven scenario becomes almost impossible. Meanwhile, the lives saved by AVs may be fewer than anticipated.

3) Decide how much traffic you want.

This is probably the key rule, because a simple understanding of economics makes it hard to avoid reaching the conclusion that AVs will result in a ton more driving. If they cut the cost of driving by 80 percent as anticipated, that's supposed to add 60 percent of the traffic to city streets that are already at capacity. That is what has gotten former mayor Bloomberg up in arms, proposing new regulation and policy to avert disaster.

But it’s actually worse than 60 percent for a number of reasons. The biggest one is called induced traffic, or the fundamental law of congestion. If you ignore induced demand, 60 percent more trips are not a problem, as long as we have swarming. Elon Musk tells us that a driving lane full of swarming AVs can handle 3 times as many cars as it does today. So, problem solved, until you realize that, these days, traffic congestion is the principal constraint to driving. Because driving is already so subsidized, we do it as much as we can, unless we are punished by traffic.

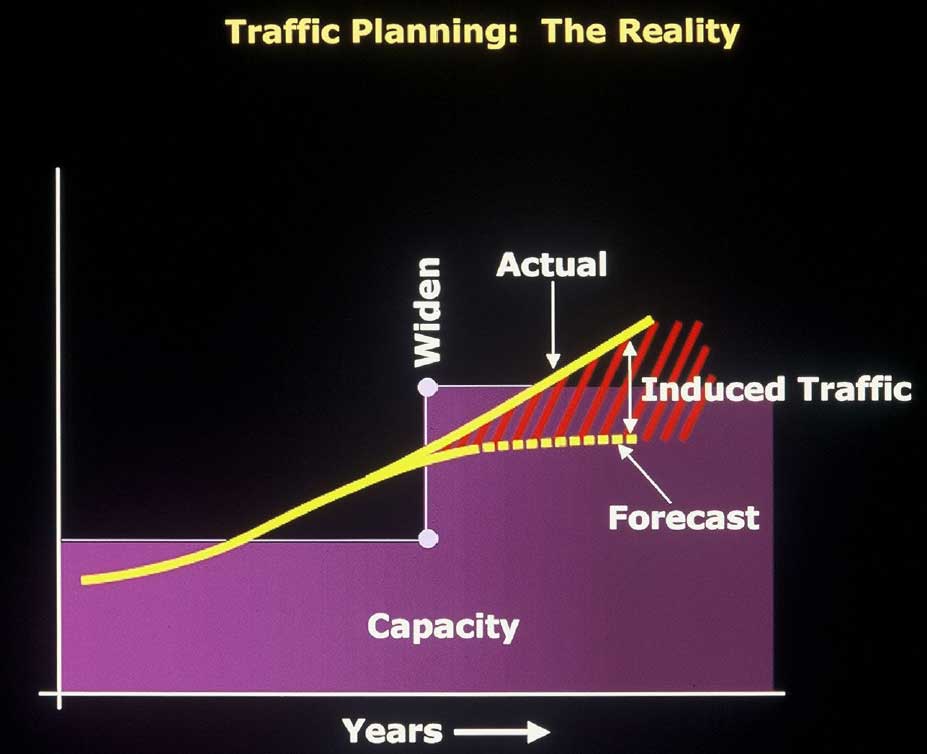

Source: Walter Kulash

Induced traffic is why highway expansions never work. Traffic engineering theory is straightforward. A street is congested because the number of drivers, shown in yellow exceeds its capacity. If you enlarge the street, you will eliminate congestion. Unfortunately, what happens instead is that the number of drivers quickly increases to match the increased capacity, and congestion returns in full force.

These are the drivers who were taking transit, carpooling, commuting off-peak, or simply not driving because they didn’t want to be stuck in traffic. When the traffic went away, they changed their habits. Maybe they even moved further away from work as the time-cost of their commute went down. Unfortunately, thanks to them and others like them, the benefits couldn’t last.

This becomes especially alarming when we realize that AVs will make driving cheaper in two ways: money and time. You will pay less per mile, and won’t mind sitting in gridlock as you work or watch cat videos.

What to do about this huge likely increase in vehicles? The only answer, I believe, is to regulate it, not with laws, but with lanes. Without a commitment to limiting capacity, all our parking lanes, soon empty, will not become bike lanes and greenways as promised, but more driving lanes. And sidewalks will feel miserable.

The right solution, is to make the streets what you want them to be. Since cars will be more efficient, you can commit to no increase in driving lanes. Maybe even get rid of a bunch! You can convert parking lanes to bike lanes and express bus lanes, which will still be needed as the AVs reach their natural state of equilibrium, which we know, from the law of induced traffic, will be determined by congestion.

4) Plan for more suburban pressure.

I recently saw this kiosk in Boston’s Copley Square, and my heart skipped a beat. Here was a Lyft ad, ostensibly for last-mile service complementing our rail network, but I’ll be darned if it wasn’t an exact map of suburban development.

Now, I’ve been fighting suburban-style development for a quarter century, with limited success, and everyone knows that it’s a function of four main factors: highways, mortgage programs, local subsidies, and racism. But mostly highways. Before the car, land development was mostly nodal, mostly around rail stops, and therefore walkable. Only with the car did the entire landscape take on wasteful, unwalkable, disconnected forms that now, more than anything else, characterize American life.

But there is recent good news, which is that cities and towns have begun to figure out that the suburban development pattern does not pay for itself. As many of you in suburban areas can attest, the tax revenue from low-density places is not enough to replace roads and pipes once they fail. For this reason, we can hope that the next great inducement to suburbanization—cheap autonomous vehicles—will not have as great an impact as universal car ownership did. But this is only a hope, which is why better policy is needed.

5) Understand transit geometry.

The discussion around AVs seems to adhere to only some of the laws of physics. What is often misunderstood is simple geometry: how many people fit in a vehicle. Even if they swarm and are small, AVs are cars, and since they’ll be used by Americans, most can be expected to hold only one rider.

Source: International Sustainability Institute

Above left are 200 people in 177 cars. They fill the street to the horizon. The other images are on bikes (upper right), buses (lower left), and on a streetcar (lower right). There is no getting around the fact that low-occupancy vehicles are a tremendous waste of street space. It does not matter if the vehicle is conventional, electric, or autonomous—geometry prevails.

This is why, when the Brooklyn Bridge was converted from part rail to all car in 1948, it went from carrying 400,000 people/day to carrying only 170,000 people/day. It’s why a single New York L train carries as many people per hour as 2000 cars, and an articulated bus equals 100 cars. Autonomous cars are a great supplement to transit, but, in congested places, they are not a solution to transit. This is why Ford is also investing in autonomous buses.

6) Don't rob transit.

This may be the greatest risk. In congested cities, replacing trains and buses with autonomous cars will cripple mobility. Now, if you are a city like Davenport, Iowa with no congestion and a very small transit population, AVs may present a solution. For Des Moines, they do not.

Unfortunately, just the prospect of future AVs is already threatening transit investment in certain American cities. The Mountain View City Council just voted down dedicated BRT lanes on El Camino Real due, in part, to the expectation of AVs making buses obsolete. The Michigan Taxpayers Alliance and others are picking up on AVs and Uber as the last great weapon to finally kill transit. Even DC’s Metro is threatened.

Meanwhile, Uber has set its sights on transit and is offering UberPool monthly memberships at lower cost than a transit pass—some say to put the conventional transit out of business. Uber admits that this pricing is well below cost and unsustainable, and thus, by definition, predatory. City leaders have the responsibility to teach their citizens about geometry—to teach them what even Elon Musk doesn’t seem to know—that a shift from transit to AV cars would reduce mobility.

7) Own the streets and own the data.

It sounds implausible, but there is a very real worry that AV providers will ask to buy certain city streets, or certain segments of city streets, and cities will take the money. This has precedents—like Chicago leasing its on-street parking to Morgan Stanley for 75 years. We need to remember that your city’s streets are its principal public spaces and, especially downtown, they perform many more jobs than just moving vehicles. They are places to walk, bike, access buildings, dine, converse, grow trees, protest, and much more, and they belong to us all.

I particularly like this recent quote from Adam Gopnik: “Cities are their streets. Streets are not a city’s veins, but its neurology, its accumulated intelligence.” Never sell that.

Another ownership issue has to do with all the traffic data collected by Uber, which cities can benefit from in many ways—for example knowing which way to send a fire truck. Like Uber, AVs will represent a viable business model only by running on public streets. Sharing full data would seem a small price to pay for that privilege.

8) Don't buy any urban vision that forgets urbanism.

If you study modern urban history, you will see that every major transportation advance has brought with it whole new concepts of what the city is. We are a creative species and we can’t help but use any excuse to reinvent the human habitat. The problem is that all of these inventions, from Le Corbusier’s “Tower in the Park” to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, have ended up making our lives worse.

The traditional city of streets, blocks, and squares has survived largely unchanged for millennia, and for good reason: Traditional urbanism was not an invention, but evolved naturally in response to human needs. The adoption of AVs should not be allowed to replace it with something different.

9) Unify around a set of policy demands.

There are a number of ways that cities will need to regulate AVs if they are to be a boon and not a bane, including owning the data, protecting transit, prohibiting empty (circling) trips, setting speed limits, and protecting traditional urbanism. Individual cities have little sway here, but working together, cities can’t be denied. Cities can all create a protocol that to present to AV providers as a collective requirement.

Such an effort has already begun at NACTO, the National Association of City Transportation Officials. NACTO’s list is a good start, but it needs refinement and expansion.

10) Invest in the current technological revolution.

A transportation technology available now has outperformed AVs by almost every measure. It travels 50 to 80 times further per calorie expended than the automobile, requires very little space, works on existing infrastructure with minimal modification, doesn’t pollute, and makes its users healthier and happier.

That technology is called a bicycle. And while the bicycle is not new, great new bike infrastructure is new. Protected bike lanes have been shown to be much more effective than conventional bike lanes. When a protected lane was inserted in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park West, the number of cyclists tripled, automobile speeding went from 75 percent to 17 percent of all drivers, injury crashes to all users dropped 63 percent. And there was no negative impact on the road capacity, even though a lane was lost.

Protected bike lanes are what you need to give a sense of security to civilian bicyclists. And with a lot of good bike lanes, you get Copenhagen, where four times as many people bike than drive.

Autonomous vehicles are the right answer to the wrong question. Why do MIT’s Media Lab, and Google keep asking how we can make cars better? Where has that question ever gotten us? A better question is: How can we provide the most useful mobility to the most people with the most positive outcomes for society? The answer includes cars, but also trains, buses, bikes, and walking—especially biking and walking.

(Top photo source: Dllu)