Turning “Renewal” into Renaissance: The Transformation of Downtown Rochester

Austin Maitland is a graduate student in urban planning at Rutgers University and shares a guest article today about his hometown of Rochester, NY. Read Austin's previous article about downtown Rochester's challenging past for some further context.

After years of mass demolition and auto-oriented commercial development, downtown Rochester has found an unexpected ally: residents. This comes after several decades of transforming downtown into a place for anyone but residents. Nevertheless, people are flocking to the center city and it’s looking like Rochester’s dead city streets may find a second life in the coming years. At the center of it all, developers are rising to the challenge of delivering attractive, urban residential options in a place previously built for cars and commuters. Likewise, the city has made strategic investments and policy reforms to aid in this renaissance. Together, private and public actors are building the next generation of downtown Rochester.

To truly appreciate the success of downtown today, it’s important to understand the definition of success in Rochester’s past. With the widespread adoption of the automobile in the early twentieth century, many believed that the level of success in downtown shared a direct, positive relationship with the width of its streets, number of parking spaces available, and height of the tallest building. The construction of the Inner Loop was considered a massive success because it improved vehicular circulation around downtown at a time when Rochester’s population was at its highest. Xerox Square, First Federal Plaza, The Metropolitan, Five Star Bank Plaza, and many other commercial fortresses were celebrated as successes for clearing blight and realizing a grand vision of a downtown of monumental scale.

Today, Rochester is a different story. Downtown office buildings are plagued with high vacancy rates, and the social and financial costs of massively expanded infrastructure have become strikingly apparent. Developers and city leaders alike have learned from the dangers of selling out to special interests and subsidizing one mode of transportation. More and more, they have embraced a new measure of success for downtown: the ability to attract and retain residents. The sheer amount of private development now following this mentality has been astounding, especially considering the contracting economy and population of upstate New York.

The early success of developers’ downtown residential push is in the numbers. Downtown’s population has swelled from just 3,100 in 2000, to 7,000 today across 3,718 residential units. On top of that, 1,700 new units are in the pipeline as developers pour $620 million of private capital into the center city.

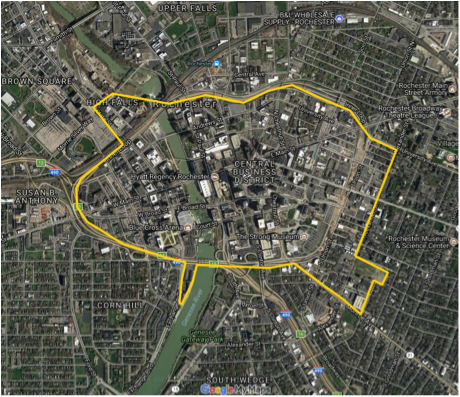

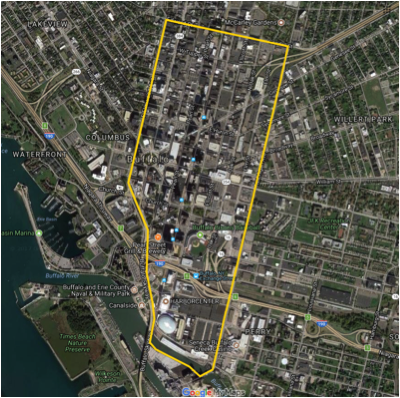

To put these numbers in context, consider nearby Buffalo, New York. In 2016, Buffalo’s downtown, similarly defined as approximately one square mile around the central business district, housed just 2,500 residents across 1,893 units. Of course, downtown Buffalo is also seeing notable investments such as the new University at Buffalo medical school, redevelopment of the waterfront at Canalside, as well as an assortment of mixed-use conversions. But even if Buffalo achieves Mayor Byron Brown’s goal of adding 2,000 downtown residential units by 2018, the total number of units will continue to trail far behind as Rochester adds 1,700 of its own in a similar timeframe. The revival in Rochester is real, and the scale of downtown residential activity is truly unique to the region.

The yellow lines mark the boundary of downtown used for the purposes of data collection.

Rochester’s numbers impress, but nothing truly illustrates the scale of the building boom like physically seeing downtown’s transformation. It is not simply the sheer number of units being brought to market, but the way that developers are creatively adapting old forms to new functions, thus attracting and engaging pedestrians downtown for the first time in generations.

At the southwest corner of Main Street and Clinton Avenue, The Metropolitan redevelopment project offers an example of the innovative spirit transforming downtown for the better. Gallina Development has taken the half-vacant, 27 story office tower and functionally cut it in half. Floors 1 through 15 continue to serve the building’s traditional commercial tenants while floors 16 through 26 are being converted into apartments and condominiums. The vast floor plates of a mid-20th century office building may seem inappropriate for residential use, but as one Gallina employee explained during an open house at the tower, such a format actually gave the company tremendous flexibility in creating unique floor plans without worrying about the placement of load bearing walls. The result is a unique mix of unit configurations at various sizes and price points. The first two floors and 28 units came online in April, and by July all had been leased.

Additionally, Gallina has changed how the building engages with the street. A series of skyways, walls, plazas, and underground passages once prevented any sort of vital street level activation. Under the redevelopment plan, a prominent entrance has been constructed on Clinton Avenue, welcoming pedestrians and allowing drivers to load and unload passengers. This is the type of activation so desperately needed as more and more people call downtown home.

Other redevelopment projects in the vicinity of The Metropolitan are notable in different ways. Buckingham Properties redeveloped the vacant 18 story Midtown Tower into a mixed-use complex known as Tower280 that opened in early 2016. A six story mixed-use addition off the west side of the building is already in the works which would activate yet another section of Clinton Avenue. Tower280 marked the introduction of modern tower living to the Rochester market to great success. It was also the first major project to demonstrate how failed commercial icons of Rochester’s past would play a key role in shaping its future.

While most of the ongoing projects involve investments from local developers, one project has attracted a prominent out-of-state developer offering even greater validation of downtown’s revival. WinnDevelopment, a Boston based firm, is investing $200 million into the historic Sibley Building just one block away from Tower280. The project follows the same formula of mixing housing, office space and retail into rebranded complex, in this case known as Sibley Square. This large investment from a prominent out-of-state developer is a first for Rochester, and indicates that the excitement surrounding downtown’s revival extends far beyond the city boundaries.

The list of private investments goes on and on to include new hotels, restaurants, apartments and offices. Shovels are in the ground and cranes in the air. It’s a sight to behold in a city long ravaged by disinvestment and population decline.

Crucially, the results of downtown Rochester’s residential transformation are beginning to show in little ways. In 2014, downtown welcomed its first grocery store in decades, Hart’s Local Grocers. This wasn’t some big shot supermarket chain claiming to be the silver bullet to downtown’s revival. Instead, Hart’s was the product of a local entrepreneur (and urban planner) who made the next logical and incremental step forward in a downtown with a growing population. A similar victory exists over at Tower280. A local restaurateur opened a second iteration of a local favorite called Branca Midtown. A new Italian place and grocery store may carry a far more modest price tag compared to other downtown developments, but the value they represent is impressive. Just a few years ago, such businesses would have required public subsidization to remain open downtown, yet today they are sprouting up organically, funded by local entrepreneurs and benefitting the local population.

It isn’t all private activity though. The city of Rochester is doing its part by strategically investing in downtown’s future as a place for residents. Main Street is in the midst of an overhaul, the Inner Loop has been filled (see images above) and awaits development, and downtown parks are coming alive, a change well-documented by Arian Horbovetz over at The Urban Phoenix.

On the policy end, Rochester has already taken the important step of eliminating parking requirements in downtown and takes a liberal approach to regulating land use in most downtown zones. The 2014 Center City Master Plan stresses the importance of human scale place-making and even warns against prioritizing parking availability: “Over 90 years of replacing buildings with parking lots has not contributed to Downtown as an attractive, vibrant, urban place.” All of this is to say that, at long last, the city’s interest has shifted from commuters to residents, a far sounder investment.

The confluence of so many promising private and public initiatives is poising downtown Rochester to be the strongest it has been in many decades. Development is proceeding in exactly the way one would hope for a strong neighborhood; the private sector takes the lead in turning vacant and underutilized buildings into financially and socially productive assets of the city while the public sector eases anti-urban restrictions, pares back costly infrastructure, and refocuses on the basics like maintaining public parks and sidewalks. The result is a new generation of downtown, one that takes yesterday’s derelict, commercial failures and transforms them into resilient mixed-use complexes capable of adapting to changing market demands. Remarkable things are happening in Rochester; although there is a long way to go, the awakening of the urban core should serve as a beacon of hope to other struggling mid-sized cities across upstate New York and beyond.

(All photos by Austin Maitland unless otherwise noted.)

Local activists in Selma, NC, started small, but they’ve grown into a coalition of citizens, civic groups, and city leaders striving to improve housing, transportation, and the local economy.