Growing Lasting Wealth in Cobb County

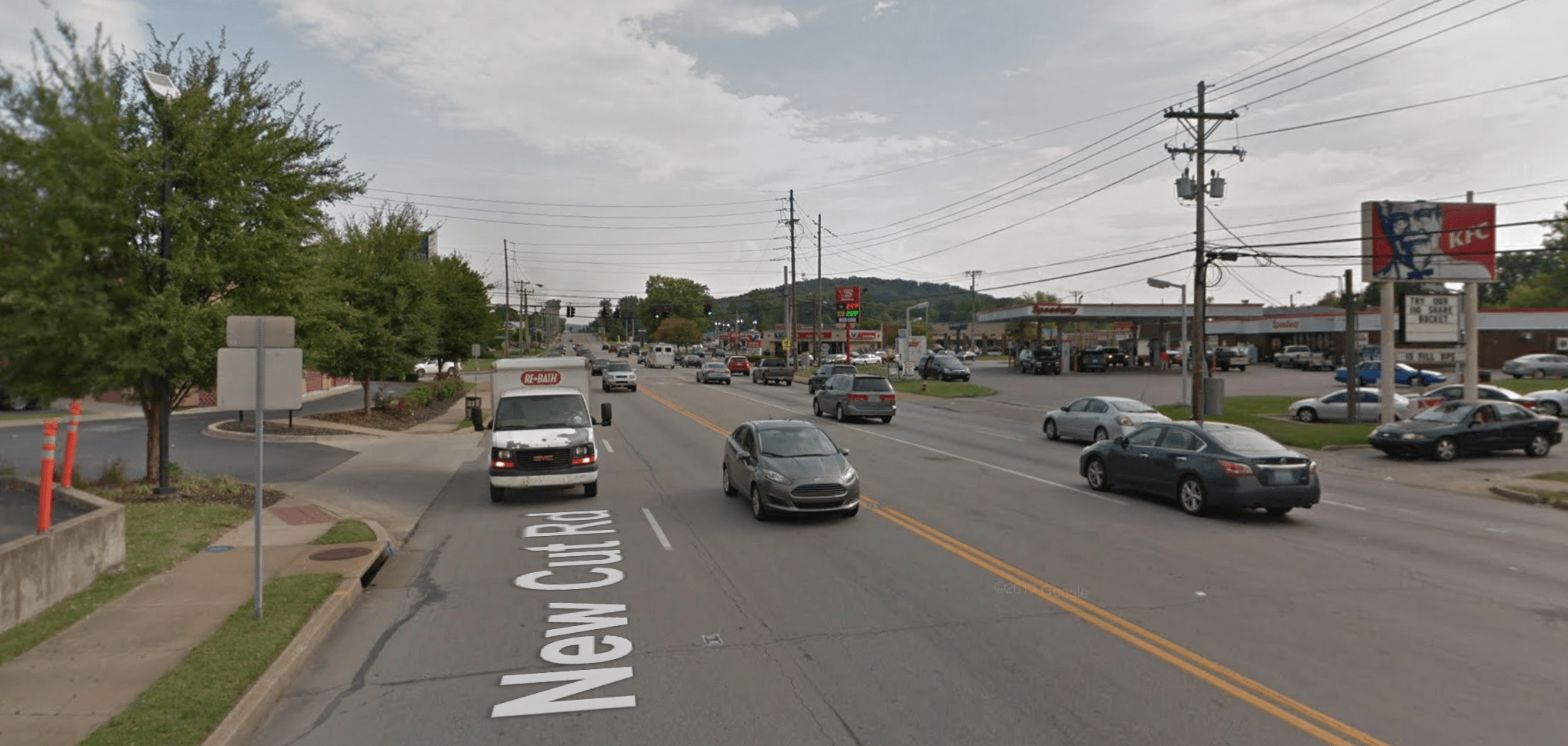

In Monday’s article, Rachel included a picture of a stroad with a distinctive KFC sign shaped like a big chicken in Marietta, the seat of Cobb County and its largest city. Below is a slideshow with the same picture, along with pictures of KFCs along stroads in two other counties. Before you read on, click through the slideshow and take a wild guess about where each KFC is.

The second picture is from a couple towns over in Gwinnett County, GA, and the third is from near the company’s headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky. But you can be forgiven if you mistook the vista of pavement and fast food for your own town. This landscape is instantly recognizable as a product of the dominant land development pattern in the United States that has taken over in so many of our places.

This pattern of building, the suburban experiment, has been implemented almost everywhere in our country, but it is especially concentrated at the peripheries of urban areas. It looks the same everywhere because it is devoid of any acute sense of place. But putting aside its complete cultural vapidity, today we’re going to focus on its dearth of economic productivity.

In Atlanta, one of the United States' fastest growing metro areas, the suburban experiment has taken over entire counties, swallowing towns that were once independent. The first ring of suburbs, including Marietta, Johns Creek, and Lawrenceville, were all newly affluent in the postwar era due to an influx of people flocking there in search of single family houses and an auto-oriented lifestyle. As Rachel said in her article on Monday:

In the '60s and '70s, Marietta was a wealthy, popular community, but once the shine wore off, rich residents got out, moving farther afield, and leaving poverty and decline in their wake.

Today, at the core of Marietta exists a tiny, blink-and-you-miss it downtown square, home to great restaurants, funky shops and civic buildings. It still draws a lot of people, but it’s now impossible to access by foot because it’s surrounded by 4-6 lane stroads on all sides.

Urban3, the geoanalytics firm from which we source many of our insights on the financial potency of cities, has not yet been hired for an analysis of Cobb County, but they have done projects in neighboring Fulton and Gwinnett counties. They uncovered the underlying pattern of land value economics in the two counties, and, judging by its nearly identical outward appearance and development history, expect Cobb County to look very similar.

Gwinnett County in particular has achieved some notoriety among Strong Towns members and Urban3 clients, since it represents decidedly the opposite of the Strong Towns approach. Chuck Marohn and Josh McCarty broke down the numbers in detail last month, and Cobb County shares many of the same woes.

This image shows the tax value per acre of plots in Gwinnett County, GA. Taller red and purple plots are those with high tax value per acre. Lower green plots are those with little tax value per acre. (Source: Urban3)

Visualizing Value

In this visualization of Gwinnett County, taller red and purple plots are those with high tax value per acre. Lower green plots are those with little tax value per acre.

Can you find the downtown? It’s hard to single out any specific pocket of concentrated value. Among all of the concerns regarding Atlanta’s continuous expansion, a major issue is the absence of a strong downtown with the potential to accumulate lasting value. In value per acre visualizations, successful communities feature a prominent spike in value where downtown-style development concentrates tax value within a modest footprint.

Such spikes of value do not exist in Cobb County because almost all new investments has been focused on suburban development. Downtown Marietta is hence undervalued and hemmed in, unable to grow in size or value.

Cobb County, like the rest of suburban Atlanta, is instead dominated by winding roads dotted with detached single-family houses and interspersed with strip malls and office parks. Even in instances where this development pattern does show a modest amount of value per acre, when we account for the enormous amount of infrastructure that is needed to support such a spread-out lifestyle, the finances of these places just don't pencil out.

In the Gwinnett County illustration above, the few purple spikes that do exist are mostly hotels and the occasional multistory office building found along a major arterial. But these places with concentrated value per acre are few and far between.

Gwinnett County lacks the infrastructure needed to support productive multistory buildings because there is not a sufficient critical mass of people to walk from one building to the next. So each potentially productive parcel needs its own oversized parking lot, and each impermeable parking lot needs its own retention pond. As a result, the value of any one productive building is severely diluted because developers need dozens of acres of wasted space to support it.

For those who think that SunTrust Park (the new Atlanta Braves Stadium) will break the cycle and create enough value to offset the fortune that Cobb County taxpayers are paying to subsidize it, a glance at Gwinnett County offers another figurative glass of cold water to the face.

Coolray Field highlighted in a choropleth map visualizing value per acre in Gwinnett County. (Source: Urban3)

In 2009, the Braves’ minor-league affiliate team moved to unincorporated Gwinnett County in a similar move, funded by tax dollars. As shown in the graphic above, the value per acre produced by Coolray Field (highlighted in the red box) has made zero difference amidst the miles of cul-de-sacs. Even the nearby highway-side mall (the large orange blob in the center) creates more value per acre than the stadium, an astounding feat since malls are our usual benchmark for poorly performing properties. Furthermore, parking revenue directed to the County was only 15% of the $200,000 that was promised. The new Stadium was a lousy deal in Gwinnett, and it’s a lousy deal in Cobb.

Comparisons in North Carolina

It’s hard to reckon with the harsh reality of this situation. It’s a little easier to dream about how things could be better. In looking for development models to emulate, dreamers in Cobb County might point to Mecklenburg County for a new direction. Mecklenburg County is the home of Charlotte, North Carolina, a city with such an annexation habit that it has now swallowed almost the entire county. Cobb is a tad smaller than Mecklenburg in both population and area, but its density is actually greater at a whopping 2,140 people per square mile.

I grew up in Charlotte, and I’ll be the first to say, it is far from a perfect city (ranking dead last among major U.S. cities in both walkability and economic mobility), but it’s undeniable that its Uptown provides its fair share of financial and cultural value for the county and region. Now, can you find the downtown in this image?

This tax value per acre visualization of Charlotte shows an economically prosperous and productive urban core. Downtown Marietta could aspire to develop like Charlotte instead of being Atlanta’s little brother by making incremental steps in a financially productive direction. (Source: Urban3)

Another region in North Carolina, the Research Triangle, demonstrates that multiple pockets of value across separate counties can coexist and contribute to a single metro area. Like many similar areas, residents of Cobb County often repeat the refrain that they don’t need a downtown since Atlanta functions as their downtown. This ignores the fact that Marietta and Atlanta are 20 miles apart. In the Research Triangle, Raleigh and Durham are 22 miles apart, and they each have their own downtown area that is thriving in its own way and on its own terms.

In the above tax value per acre visualization, Durham and Chapel Hill, only 22 miles apart, prove the possibility of two adjacent but distinct pockets of downtown wealth. (Source: Urban3)

Marietta should aspire to grow its own downtown instead of pretending that Atlanta is its downtown. Assuming that the pattern found in Johns Creek and Gwinnett County extends throughout the rest of the first ring of suburbs, it’s extremely likely that Cobb County imports as many commuters as it exports on any given workday. There’s no reason that they should not be able to retain their wealth and create more complete neighborhoods in the process.

Comparing counties is an art and not a science, even among counties with similar sizes, populations and densities within the Southeastern United States. But the numbers don’t lie; the major differentiating factor between Mecklenburg and Cobb is between one development style that grows lasting wealth and another that does not.

Growth is not enough, and density is clearly not enough either. What suburban Atlanta needs—what all of us need—is a development pattern that creates productive growth. At the tail-end of the Growth Ponzi Scheme, and with nowhere left to expand, Cobb County is at a crossroads. The region certainly can’t afford to make another investment as bad as SunTrust Park.

Because if Cobb County doesn't choose to build in a way that grows lasting wealth, they will continue their downward spiral into debt and poverty. Communities like Cobb County must address the problems that have plagued them from the outset by encouraging a compact style of development that produces true value per acre. It’s not a matter of whether they can afford to invest in their downtown. The fact is, they can’t afford not to.

Tomorrow, we'll discuss the on-the-ground impact that this failing development pattern has on the people of Cobb County.

The Finance Decoder reveals the long-term trends hidden behind annual balanced budgets. For Kansas City, those trends are deeply problematic.