Best of Blog: Stroad Nation

This is my last post of 2014, and it's right that we should end with Ferguson, a story that I think defined this year as well as America at a very difficult time.

In the past year, I read three books on the complex mess that was the prelude to World War I, similar books on the American Revolution and the U.S. Civil War and a book that included the same basic information on the rise of Nazi Germany and the events that brought about World War II. Part of this was interest spawned by the 100-year anniversary of the beginning of the Great War, but a lot of what I found compelling was the way the complex problems of the day were unable to be resolved peacefully.

I learned in basic history class that World War I was caused by the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife. In an advanced class, we talked about how that event might have been the spark, but the real cause was the complex web of alliances that spun everything out of control. Today, I would not point to either of those as the cause. In my estimation, "the cause" (if there is one such a thing is a massively complex system) was a decades-long shift in the power structure from the old powers of France, England and Russia to Germany. As Germany was rising, alliances were put in place by those old powers to contain it. There were attempts at treaties to limit military advancement (prohibit certain size artillery, for example) in an effort to maintain the current balance of power, but to no avail. Many in France and Russia believed they would need to fight Germany at some point or lose their dominant political and economic status. Many in Germany knew this and knew they couldn't win a two-front war if France and Russia were allied. In response, Germany developed the only military strategy that had a chance of working: a preemptive attack to defeat France before England could deeply engage, then a quick pivot of forces to hold off Russia. When the Archduke was killed and it looked like a war might break out, the preemptive nature of Germany's defense meant there were few options left to avoid total war. Only some great and visionary leadership -- which happens occasionally throughout history, but not as often as we might believe -- could have diffused the situation. And even then....

In the past few months, we've been treated to all the cheap punditry and platitudes typical of unfolding events. We were told by some that the things happening in Ferguson were caused by racist cops and a police department disconnected from the population it serves. We were told by some that the cause was simply one man's failure to do as he was told, a reflection of a culture of lawlessness. These and other explanations are put forth to affirm one worldview or another. Like all such narratives, they use one brick of truth to support a distorted edifice of belief.

I don't pretend that Ferguson is an easily-explainable event today, and I don't think history will find it much easier. Still, the grinding of forces that I see at work -- the grand stage on which this is being played out -- has little to do with overt racism or lawlessness and more to do with shifting power. Those with it want to keep it while those without, understandably, would like to acquire some. This is why the demographic cries of "whites becoming a minority" has been played on shrill repeat for years. Even though it doesn't matter, it taps into our cultural understandings, whether it is a fear of losing what we have or anticipation that our time is somehow coming.

Tragically, the layout and design of America -- the very pattern on which we have built our places over the past two generations -- could not be more perfectly designed to amplify our fears and insecurities. The natural mixing of humanity necessary to not only create shared understandings but diffuse conflict has been designed out of our society. As Bill Bishop has documented in The Big Sort, we've been able to self-select into pods of like-minded people who not only share an increasingly narrow band of socio-demographic characteristics but don't even interact with each other all that much. When I look out my window and see a world that looks like me, it's pretty easy to start believing that is the world, especially when the algorithm that provides my Facebook feed confirms it. This is a tragedy for rich and poor alike.

And as the auto-oriented pattern of development that dominates North America amplifies our insecurities, it also undermines the essence of who we like to think we are: a land of opportunity. There has been a lot made of the growing gap between the incomes of rich and the poor, but where the effect is most pernicious is in land. I was in Greenwich Village earlier this month and noted the $20 million row houses. I was in Philadelphia earlier in the year and saw similar homes boarded up with the homeless sleeping in front. There is an ample amount of privileged angst over gentrification, but those places are the exception. The vast majority of impoverished places stay that way. And with the suburban ponzi scheme playing out, that list is growing.

Ferguson is trapped in a cycle of decline, not because of its people or even their poverty, but because it is designed to be that way. That wasn't some intentional plot for oppression but it is the natural byproduct of this auto-based, government-led development experiment we have undertaken. Failing suburbs are where the power shifts of our time are concentrating desperation and discontent. Sadly, Ferguson will not be an anomaly.

In December of 1914, as the initial battles of World War I wound down and the combatants settled into the trench warfare the conflict would become known for, something beautiful happened. What has come to be known as the Christmas Truce of 1914 broke out up and down the lines. It wasn't a truce brokered by the politicians or the military leadership -- they were actually opposed and worked to thwart it -- but a spontaneous action of the troops themselves. Soldiers who had been killing each other days earlier put down their weapons, gathered in no-man's-land and did what people's hearts naturally guide them to do: they rediscovered their humanity. They shared cigarettes and chocolates, sang Christmas carols and played games of soccer. They were at peace.

I'm firmly convinced that the great problems of our age won't be solved by great leaders, the right government policy or some new program but by all of us working to rediscover our humanity, and the inherent beauty within those around us, as often as we can.

Thank you to everyone who has become part of Strong Towns this year, whether as a reader, listener, contributor or as one of our 662 members. If you'd like to join that latter list and be member #663. we'd love to have you. Regardless, thank you for all the times you've shared our message with others. I wish you all peace and happiness throughout this season and into the new year.

We can’t over-simplify the dynamics of all that has happened in Ferguson, but it’s obvious that our platform for building places is creating dynamics primed for social upheaval. The auto-oriented development pattern is a huge financial experiment with massive social, cultural and political ramifications. It is time to start building strong towns.

I don’t have cable and so I’m not in touch with the news cycle that many of you that watch cable news experience. I feel my life is better for it, although there are times when I do sense I’m missing some of the soul and substance of an issue getting my news primarily from print sources (and those, primarily of foreign origin). The ongoing matter in Ferguson is one of those instances. Add in the racial complexity – of which I am, by my own admission, lacking in intimate understanding – and I feel at an even greater disadvantage. I’m going to tread where I feel on solid ground, knowing others have more to contribute on this subject but hoping I can offer some relevant thoughts that you have not heard in other places.

I’ve spent some time on Google looking at the area where the shooting took place and the QuikTrip that was the flashpoint for events that followed. While this is a fairly ubiquitous pattern of development here in the United States, there are some important things to note. What I see with Ferguson is a suburb deep into the decline phase of the Suburban Ponzi Scheme. The housing styles suggest predominantly 1950’s and 1960’s development. We’re past the first cycle of new (low debt and low taxes), through the second cycle of stagnation (holding on with debt and slowly increasing taxes) and now into predictable decline. There isn’t the community wealth to fix all this stuff -- and there never was -- so it is all slowly falling apart.

Decline isn’t a result of poverty. The converse is actually true: poverty is the result of decline. Once you understand that decline is baked into the process of building auto-oriented places, the poverty aspect of it becomes fairly predictable. The streets, the sidewalks, the houses and even the appliances were all built in the same time window. They all are going to go bad at roughly the same time. Because there is a delay of decades between when things are new and when they need to be fixed, maintaining stuff is not part of the initial financial equation. Cities are unprepared to fix things -- the tax base just isn't there -- and so, to keep it all going, they try to get more easy growth while they take on lots of debt.

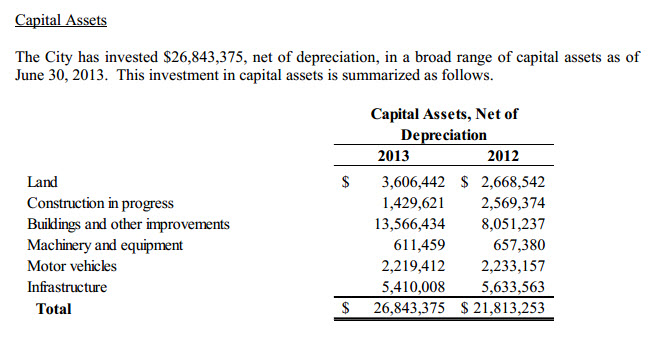

In 2013, Ferguson paid nearly $800,000 just in interest on its debt. By comparison, the city budgeted $25,000 for sidewalk repairs, $60,000 for replacing police handguns and $125,000 for updating their police cars. And, like I pointed out last week, Ferguson does what all other cities do and counts their infrastructure and other long-term obligations as assets, not only ignoring the future costs but actually pretending that the more infrastructure they build with borrowed money, the wealthier they become.

Ferguson isn’t all decline, however. They have the now infamous QuikTrip and all the other stroad development types that thrive on places in decline. Multiple car lots – some abandoned – strips malls, drive through restaurants, a Dollar Store and then you have a quarter million dollars of infrastructure supporting these storage sheds. This is an investment that employs nobody, creates little value and doesn’t even use the sewer/water/sidewalk that has been built there at enormous public cost.

One of the saddest buildings is the Ferguson Market and Liquor Store. Look at it. Understand that there is something close to $300,000 in public infrastructure adjacent to that site. That’s a huge public investment and an enormous ongoing commitment that the taxpayers of this community must shoulder. What do they get for it? There is all this waste of asphalt for a drive-through ATM. Then look at the fence on the right side, as if it is so offensive that one would seek to walk from the market to the McDonalds. And speaking of walking, that $25,000 being spent on sidewalks is obviously not being spent here. How about $50 for a shade tree?

When places like this hit the decline phase – which they inevitably do – they become absolutely despotic. This type of development doesn’t create wealth; it destroys it. The illusion of prosperity that it had early on fades away and we are left with places that can’t be maintained and a concentration of impoverished people poorly suited to live with such isolation.

Once we reach that stage, what opportunities does our development approach provide? The Ferguson planning documents are full of talk of infill and using tax subsidies to attract development. We can see what infill looks like. Here is a photo of the approximate location where Michael Brown was shot. Note the infill housing on each side. Our zoning codes dictate clusters of housing that are at one price point. Single family residential. Multi-family residential. M-2. M-3. etc....

Even if the initial price point is high, the cycle of decline brings it down over time. The buildings are auto-oriented – parking minimums force that logical adaptation – and so they present a rather despotic front to people not in a car. There are no eyes on the street, the buildings all orient towards the parking lot. And nobody even cared enough when this was built to plant some shade trees next to the sidewalk so people could walk in a modest amount of comfort.

Are we surprised that two men would be walking in the street here? If they were going to be on the sidewalk, they would need to march single file.

Earlier this year I wrote about Dunkin Donuts and their franchise model. You need a net worth of a half a million dollars to start a Dunkin Donuts. How many people in Ferguson have that kind of wealth? The median household income in Ferguson is 21% less than the state average. The median house is worth 32% less. How would the average Ferguson resident, living in a community programmed for decline, build enough wealth to start a doughnut shop?

The reality is that they can’t. So they don’t. So the business subsidies and the millions of dollars of public investment in infrastructure go to the typical cast of characters. A full 22% of Ferguson’s employed males and 21% of employed females work in retail or food service. Those are low wage jobs where, like the Dunkin Donuts, the profits rarely stay in the community. Where is the wealth to take that abandoned strip mall, convert one of the bays to a donut shop and make a go of it? It’s not there. What little wealth there is being sucked out of the community.

Let’s pretend that there was some wealth. Let’s say we have someone in Ferguson – and I’m sure there would be lots of candidates – with some real entrepreneurial zeal. They want to start a business in one of those abandoned buildings. How many zoning regulations, public hearings, parking requirements, building inspections and general red tape would they need to go through to make that happen? How does that impact the cost of entry? We establish all these things on the way up, insist they are part of the way we will keep order during the stagnation and then stubbornly refuse to challenge our assumptions on the way down. Of course, the city seems eager to help, if you are in the right place and will be paying sales tax. (Note: they at least appear to allow food trucks to some extent.)

This stroad nation we have built is also not well equipped for the transportation needs once a place goes into decline. Despite being relatively poor in comparison to state averages, 86% of employed people in Ferguson drove to work in a car by themselves, an incredibly expensive ante to be in the workforce. Only 3% used public transit while 9% carpooled. That leaves less than 2% able to use the most affordable option available: biking and walking.

If you live in Ferguson, you are essentially forced to drive for your employment and your daily needs. That is the way the city was designed. There was no thought given to the notion that people there might not always be prosperous, that they might desire to – or have an urgent need to – get around without an automobile. When you look through the city’s planning documents, you see that walking/biking infrastructure still primarily means recreation, not transportation, despite the obvious desperate need for options.

Unfortunately, nothing I’ve brought up here is really unique to Ferguson. All of our auto-oriented places are somewhere on the predictable trajectory of growth, stagnation and decline. Racial elements aside, I think we are going to see rioting in a lot of places as this stuff unwinds. The most insightful thing I’ve read on this subject over the past couple of weeks was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s column in Time magazine.

This fist-shaking of everyone’s racial agenda distracts America from the larger issue that the targets of police overreaction are based less on skin color and more on an even worse Ebola-level affliction: being poor. Of course, to many in America, being a person of color is synonymous with being poor, and being poor is synonymous with being a criminal. Ironically, this misperception is true even among the poor.

And that’s how the status quo wants it.

We’re entering a really dangerous phase of this Suburban Experiment. While we once believed that the path to prosperity was the “American Dream”, a house in the suburbs and an ownership society (FDR saw this as a social equity issue as did GWB), it is now evident that this approach creates poverty. It not only creates it, it locks it into place in a self-reinforcing cycle. Like I’ve said before, how we respond to this is the social challenge of this generation.

So far, I’m more worried than anything else. I joined the Army on my 17th birthday and spent the summer between my junior and senior year of high school at basic training. Despite the total exhaustion, there were two nights I just couldn’t sleep: the night after bayonet training and the night after our first day shooting the M-16 at pop up targets, which were silhouettes of people. Just contemplating, even at a very detached level, the notion that I might be asked to take a human life was a very sobering notion for a 17 year old. Simulating the act was eye-opening. Fortunately I was never faced with the moment where I had to do the real thing. I don’t know how I would have reacted.

It is with that background that I find myself beyond horrified at police officers – not even soldiers but public safety officers – in full camouflage gear pointing their weapons at American citizens. I even saw photos of a sniper. A sniper! Snipers are used to take down targets with stealth – terrifying – and we’re deploying them during social unrest. My mind is just blown. I don’t think we – as sober citizens – can overreact to this reckless display of force. You never point a weapon at a person unless you are prepared to kill them. Is that what we’ve come to?

We’d better hope not. We’ve bought ourselves some time with our extraordinary monetary policy – given the baby boomers a chance to sell their suburban homes and get some of their retirement savings back – but I don’t see us being able to keep this thing propped up a whole lot longer. Maybe we can – I’ve been surprised thus far, after all – but I suspect that more and more places will hit the decline phase of this experiment in the coming years and not get the bailout they are hoping for. The money just isn't there.

A lot of cities are going to need a Strong Towns approach when that happens. While I’m not trying to over-simplify the dynamics of all that has happened in Ferguson, it’s obvious that our platform for building places is creating dynamics primed for social upheaval. Our auto-oriented development pattern is a huge financial experiment with massive social, cultural and political ramifications. It is time to start building strong towns.