The Lies We Accrue

Pinocchio c/o Wikimedia.

Back in my early days of professional employment, I took a loan withdrawal from my company's 401(k) plan and used it to buy a car. For those of you are not familiar with this kind of retirement plan, the 401(k) regulations allows one to borrow from themselves and pay themselves back, with interest. The payback comes out of your paycheck, just like a 401(k) contribution.

My reasons for doing this had more to do with interest rates and loan terms than anything else, but it was also an easy way to get a nice chunk of capital when I needed it. And from an accounting standpoint, this was rather genius. This loan to myself didn't show up anywhere on any credit report or loan document. From a cash accounting standpoint, I had no liability, just more money.

This is because my 401(k) balance hadn't changed: I now had a 5-year note (from myself) paying 5% instead of an investment in a mutual fund. I now had a car but I had no debt to a bank. Sure, my paycheck was a little lighter because I chose to pay myself back AND continue to stuff my retirement account, but from an accounting of my assets and liabilities, I had just created thousands of new wealth out of thin air. The left hand owed the right hand while I enjoyed a new ride.

Last month, the Atlantic took on an obscure but critically important aspect of municipal accounting: cash versus accrual. I love the way they explain the difference and so I will just pass along an excerpt:

It may be easiest to think in terms of personal finance. Imagine you purchase a car for $20,000 in 2015, but under a special promotion no payments are due on your bill until 2018. In what year did you incur the $20,000 bill? Most people would say 2015, the year you acquired the car. That’s the answer mandated under accrual accounting, a method of financial reporting required of all public companies by the Financial Accounting Standards Board. But many state and city legislatures disagree. They operate with the conviction that a bill is not incurred until the money leaves your bank account to pay it. So if you choose not to pay the bill for your car until 2018, for accounting purposes the bill will only appear that year.

Oh the ingenious ways we find to lie to ourselves.

So your current city council gets a state/federal grant to build a new business park. Or a developer comes in and extends the local frontage road, and all the underground utilities, out to the new strip mall. As I explained last year, all this new infrastructure is counted as assets. That means the city is suddenly a lot richer. Along with the new taxes from that new development -- more cash today -- they report to anyone interested in looking at their books that they also added a lot of wealth.

Any wonder why growth = good is an unassailable law of government dynamics?

What's really going on is that, along with this asset, the city promises to maintain all of that new infrastructure. In other words, they take on a liability. If local governments -- or state and federal governments for that matter -- had to follow accounting rules of the sort that we would find proper and necessary for less important institutions, those promises would be recorded as real, financial liabilities.

This makes a huge difference. For those of you that have heard me say for years that almost all U.S. cities are financially insolvent yet have thought, "that can't be true," here's an example from that Atlantic article:

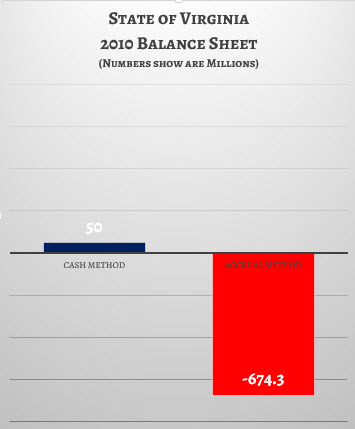

In 2010, Virginia reported that it had a cash-basis surplus of nearly $50 million in a budget of $34 billion. When converted to accrual accounting, the surplus turned into a $674.3 million deficit.

I'm a graph person. Here's how that would be represented visually.

This is why I look dumbfounded when people -- like the mayor of Allentown last week -- tell me that their city is doing great, they are making wise investments and, in a sense, they've got it all under control. They have not a clue.

And there are still some out there who think this stuff doesn't matter, that because our cities can cash flow their bills today that they don't have to bother worrying about their long term solvency. As one of my local councilor's told me, the bill on that new pipe won't come due for decades. That'll be someone else's problem. Until it's not.

Once again, from the Atlantic:

Among the many shortchanged by the city’s bankruptcy, Detroit’s retired municipal workers have gotten a particularly raw deal. The [restructuring] plan imposed deep cuts in future pension and health-care benefits. Perhaps more galling, it also required retirees to pay back a decade of interest they earned on city-sponsored retirement savings accounts. These so-called clawbacks averaged nearly $50,000 per retiree. In one circumstance, a retiree returned $96,000.

I just got done re-reading The Big Short in anticipation of the movie coming out next week. The notion of a clawback for municipal workers -- something that will happen more and more as the Suburban Experiment unwinds -- is barbaric in the context of the collective billions Wall Street executives walked away with after rigging the financial system to fail.

Yet, municipal bankruptcy is barbaric. It will hurt good people, those who ostensibly played by the rules as well as those who have not yet begun to play the game.

Let's stop lying to ourselves and start building strong towns.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.