Why Planning?

Portrait of the artist as a young hiker.

It's a glorious early fall Monday in Minneapolis, the kind of warm, dry, clear day that is the reason people here put up with the weather the rest of the year. I'm on the University of Minnesota campus, beginning my second week of study toward a Master's degree in Urban and Regional Planning. The fact that I grew up right across the Mississippi River in St. Paul has a lot to do with my decision to come back here for graduate school—I have an abiding love for my hometown, my family still lives here, and it's great to be back up north. (Though you should probably ask me again in late November.)

One question that I reflected on in deciding to take this career step for myself, and that was greatly informed by the work I've done with Strong Towns, was, "Why planning?" What am I hoping to do with this degree? What will I do with it that I can't do without it? Is this where I can do the most good?

We're hard on planners here at Strong Towns. One of our favorite themes, which I myself have written about, is the limitations of top-down planning and micromanagement. Cities are complex systems. They are full of informal relationships—spatial, social, economic—that defy easy explanation and that make a mockery of our attempts at prediction. Government intervention in such systems, more often than not, has a track record of being "orderly but dumb." At its worst, it can be horrifically destructive. (I'm a full proponent of planners observing a National Day of Atonement for mid-century urban renewal, preferably on Jane Jacobs's birthday.)

Strong Towns is also distinguished by having a broader, more eclectic membership than often-like-minded organizations like the Congress for the New Urbanism, which are dominated by "APEs"—"architects, planners, and engineers." This was clear at our national gathering a year ago, which was attended by plenty of those people, sure, but also a remarkably broad swath of activist citizens of all stripes. We appreciate at Strong Towns that there are a lot of ways to be an agent of social change, and that within the bureaucratic power structure is often the absolute worst place from which to effect any sort of transformative progress.

In fact, often the best thing urban planners can do when urbanism is working well is stay the heck away. Nate Hood's recent post on an "entertainment district" vs. an organically revitalized area in Milwaukee drove this point home nicely. The best urban places happen without a whole lot of government planning involvement. This has always been true. This was true centuries before there were professional planners, or planning schools.

So why go into a career in planning at all? This is really two separate questions:

1. Why have planners, period?

2. Why do I want to study planning?

Can we start with "Not this"?

The first one is an enormous question. Even if I were the guy to answer it, and I'm certainly not (though there are many good answers), it would take volumes. But let me talk about the second, and how my involvement with Strong Towns has influenced my thinking on this question.

I come from an environmentalist background. That's always been my passion. My undergraduate major was an interdisciplinary study of conservation and sustainable development. And urban planning is the mother of all conservation problems right now.

This is true on two levels. One is that human activities lead to ecological destruction at home and elsewhere. The spread of cities worldwide is the primary driver of high levels of energy and natural resource consumption and of the destruction of wild land for development. It is impossible to address global climate change without addressing how people live, and how they get around, in cities.

But there's another level on which urban problems are ecological problems.

Cities are ecosystems. They're full of artificial elements, sure, but they exhibit all the features that define an ecosystem, most notably the immense complexity of the relationships and cause-and-effect connections within them. We're far from the only species to modify and construct our environment—you can draw an evolutionary line from an ant colony or beaver dam to Times Square if you want.

Cities are the habitat of choice for a majority of the human species, the most consequential animal species on this planet. They are a habitat we don't fully understand. And they are a habitat undergoing tremendously disruptive change.

In 2011, I moved to Southwest Florida, one of the regions hit hardest by the fallout of the subprime mortgage market's collapse. I found myself living in an absolutely charming old neighborhood full of 1920s bungalows on the edge of thriving downtown Sarasota. My wife and I rented the mother-in-law cottage shown below. We walked to the Farmers' Market many Saturday mornings.

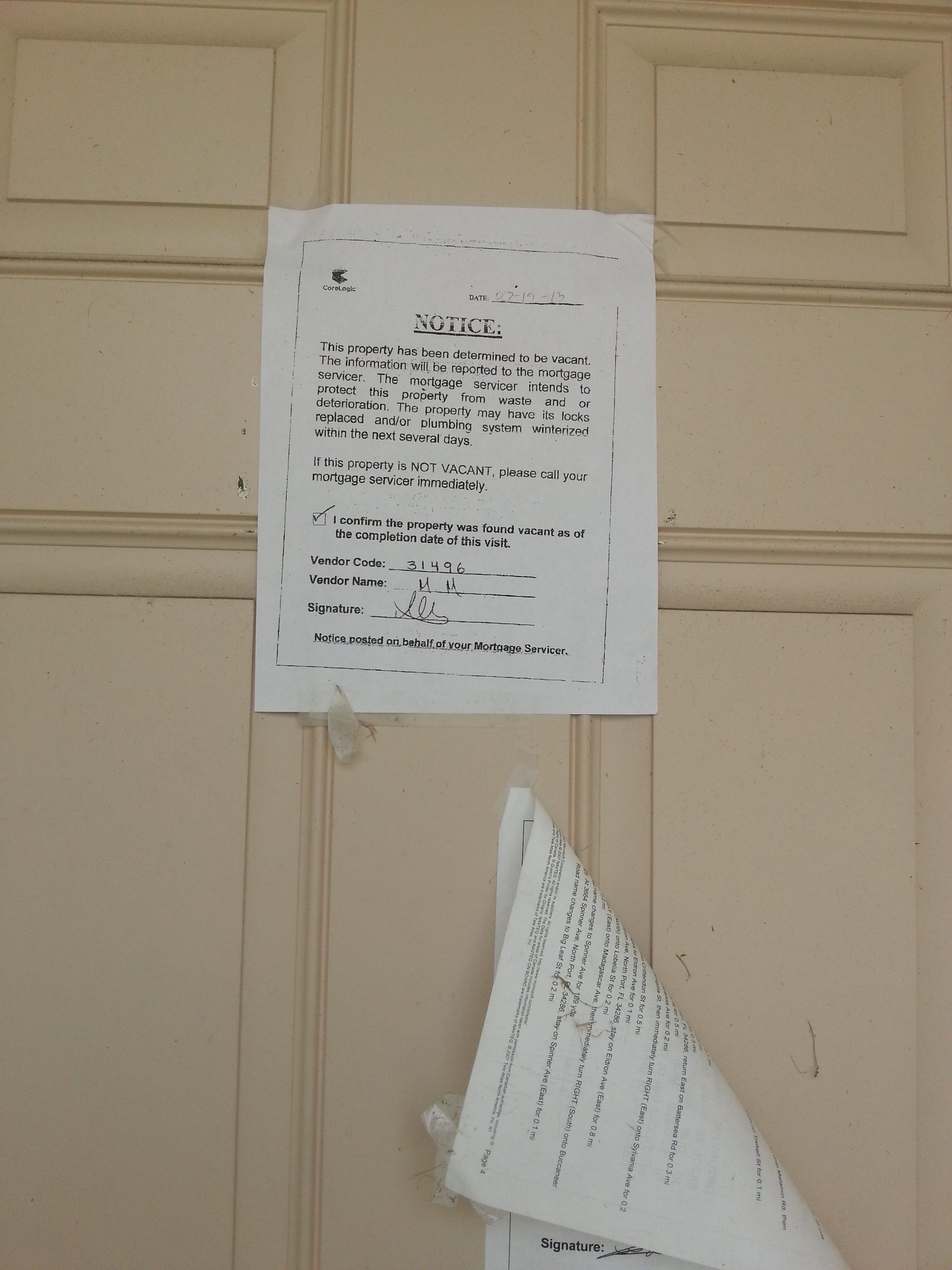

But at the same time, that neighborhood was not far from things like this:

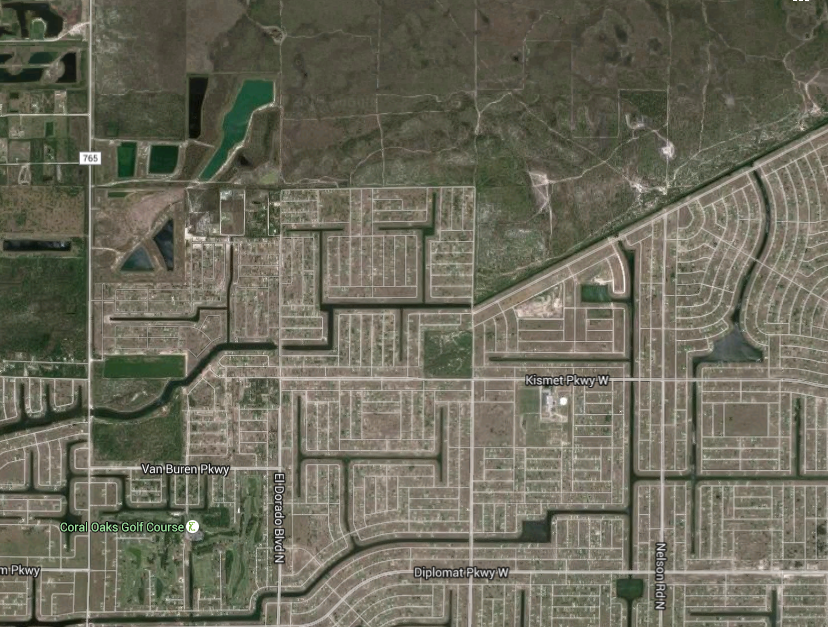

This is North Port, on the southern edge of Sarasota County. It, along with the nearby "cities" (if you can call them that) of Cape Coral and Lehigh Acres, was ground zero for the collapse of the exurban housing bubble in Florida. Massive numbers of homes are still in foreclosure. This is what some of the worst parts of the region look like from the air:

This is an ecosystem—a human habitat—in crisis.

Why do we have conservation biologists? Why does the National Park Service do ecological monitoring and management? It's a complex system. It's beyond our control. Leave well enough alone, right? The answer is that we need to intervene when things are precarious—targeted interventions that respect complexity but seek to help the system recover some sort of equilibrium.

It's the same with the human body. When your body is healthy, you don't go see a doctor for cutting-edge treatments that promise to make you even healthier. You hopefully do watch diet and exercise—things that promote ongoing health, things that work with the complexity of your body and not against it. But mostly, you go about your life and let the body do its thing. When you're sick, though, you see a doctor.

Similarly, there's not a whole lot of good that urban planners with "cutting-edge treatments" can do in a well-functioning, prosperous, totally fiscally and environmentally resilient city. Well-intentioned interventionism will likely screw things up.

But are there any such cities left? Cape Coral and Detroit deal with depopulation and abandonment, while San Francisco's artists and schoolteachers are leaving the city in droves because the place is so prosperous and desirable that nobody but the rich can afford to stay. And later this century, when the brunt of climate change's impacts start to really be felt? The Southwest is running out of water. Manhattan risks catastrophic flooding. Under some sea-level-rise scenarios, Miami is a lost cause. And most of the car-dependent heartland, if it doesn't face ecological ruin, certainly faces fiscal ruin without a major course correction.

Our cities aren't healthy. Most of them are far from stable and resilient. And planners need to be, not necessarily the doctors, but definitely the conservation biologists of cities. Our job is to understand many of the facets and interconnections of the urban ecosystem, enough to at the very least have a pretty good idea of what not to do (because it will make things worse).

This is a very different role from the way the profession imagined itself in the mid-20th century. Planning went through a crisis of confidence amid the disastrous results of urban renewal, the freeway revolts of the '60s and '70s, and widespread condemnation of the hubris of Robert Moses types seeking to impose an inhumane order on the organic city. But I really do think the field has emerged a lot stronger because of it. We still struggle to gain the public's trust, in many cases. I get it. I don't mind. That trust was betrayed so badly by the arrogance of a prior generation of bureaucrats and aloof micromanagers that we should have to re-earn it.

But the good news is planning is ahead of a lot of other fields in the social sciences and public policy. We've learned some humility about the limits of our ability to manage complexity, of a sort that still seems lost on too many civil engineers and macroeconomists, to name just a couple disciplines. I think we're ahead of the game on this—though it's something that needs constant reiteration.

Already in my first week of classes we've talked a lot about inclusive community consultation, and in a nuanced way, not just, "How do planners, as representatives of the government, best win the public over to what we've already decided we want to do?" There are massive cultural and institutional obstacles in the way of effective planning, but when I talk to people, I see a profession that's working really hard to get it. We get that we need to be grounded in the community and in our role as the facilitators and advisors of a broad, collective conversation about the use of shared land and resources. That's a conversation that is essential as cities undergo rapid, and in places cataclysmic, changes. The alternative is a free-for-all where those with the most money, power, and political connections will shape our cities to their vision.

I think it's a very exciting time to be entering the field of urban planning. And I hope lessons from Strong Towns will inform my study and my work in useful ways.