The Case Against Urban Corridors that act like High-Speed Highways

Steve Wright and Juan Mullerat are supporters of Strong Towns who run PlusUrbia, a design firm in Miami that is hoping to return a major stroad back to the people. This piece was originally published on the CEOs for Cities website, and it is reprinted with permission from the authors.

From the beginning of urbanized America, streets functioned to provide mobility in many ways:

People walked to work, trolley, horse-drawn then powered moved workers from factories and offices to home. Trains played a role in commutes. Bicycles incited a pedal power mobility craze for a while.

Then the automobile came along. By the 1950s, roads became the sole domain of automobiles. The automotive industry even created the term “jay walking” and launched a campaign to demonize people on foot. Sidewalks shrunk and beautifully landscaped medians were torn out to create more lanes for automobiles.

Trolley lines were ripped out and replaced with buses. But buses were devalued and branded as last ditch transportation for the unfortunate. Only the sedan was fit for the upwardly mobile middle class American. Crosswalks were diminished. Those brazen enough to move around on two feet were seen as merely an impediment to moving more cars faster.

Government loans encouraged suburban single family homebuilding, giving rise to the super highway, and when highways weren’t enough, surface streets – even the most picturesque and historic – were overhauled to turn them into another layer of de facto highways.

After a half century of destroying hundreds of urban corridors for the sake of the almighty automobile, sanity started to creep back into the minds of elected officials, town planners and constituents.

Milwaukee, San Francisco and other major cities razed elevated highways that had torn apart their urban fabric. Boston paid billions to put its in-town highway underground, with acres of urban park space and connectivity built above. Miami, which consistently and tragically ranks near the top of annual lists of the most deadly cities for pedestrians in America, is slow to offer options for pedestrians, bicyclists, public transit riders, wheelchair users and others who do not wish to be beholden the automobile.

Construction for I-95 tore apart the city’s historic community. Car dependence reigns supreme despite tens of thousands of dwelling units being built in what should be a walkable urban core. Because Miami grew up in the car age, its commute times are among the longest in America.

Something has to give.

Miami’s PlusUrbia Design, a design practice dedicated to creating better places, is trying to undo car culture chaos in its hometown. The studio, known for its acclaimed Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization District plan, is working to save Miami’s best-known street.

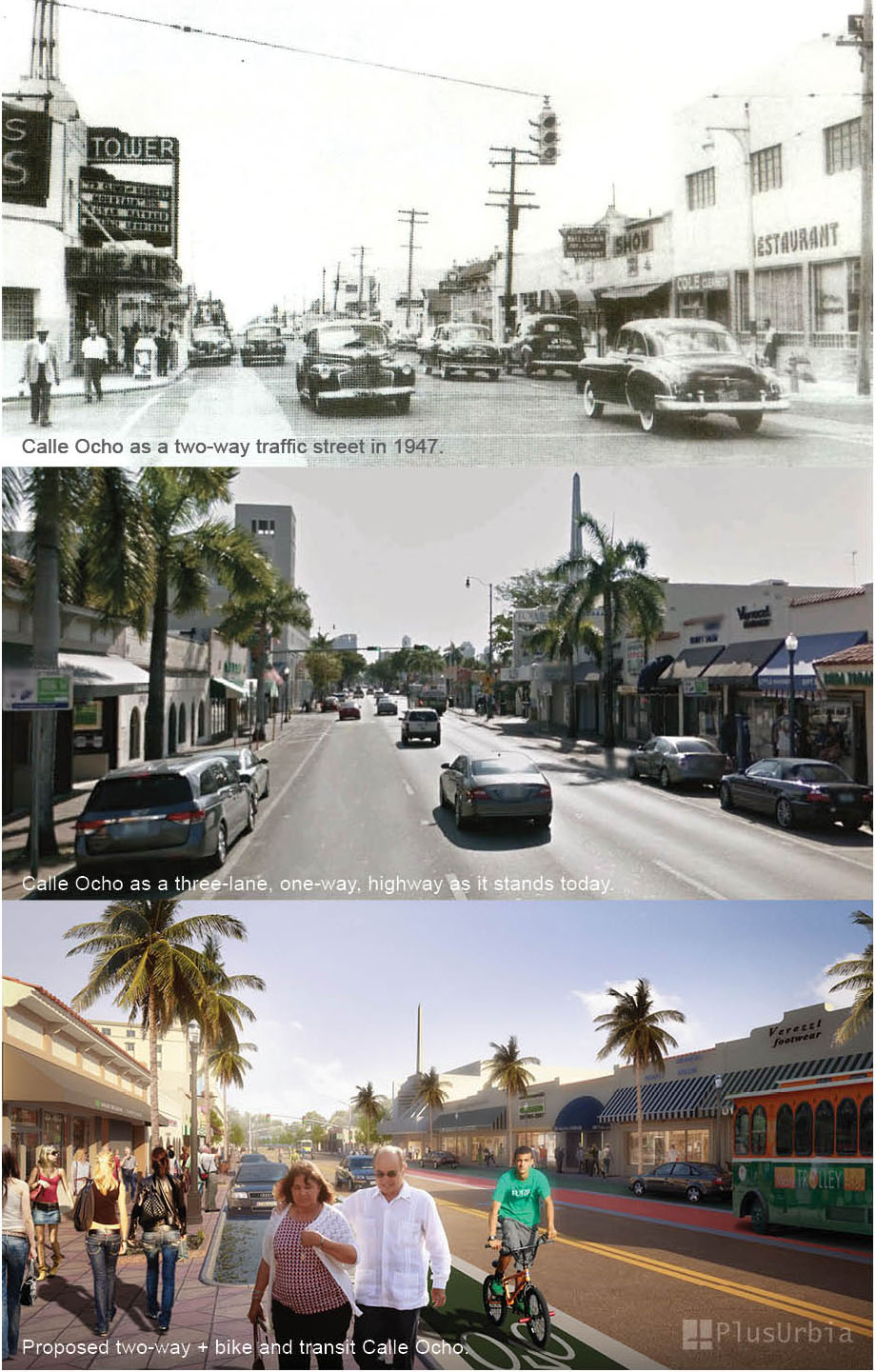

Calle Ocho, the heart of Little Havana, functions as a high-speed highway into Downtown Miami and Brickell, its financial district. Two PlusUrbia team members, who each live in historic homes just blocks from Calle Ocho, have dubbed the dangerous road “Highway Ocho.” For half a century, Calle Ocho (SW 8th Street) has served as an eastbound speedway for commuters, along with the equally dangerous one-way, three-lane, westbound SW 7th Street. It is time to make streets for the people, not simply for cars.

Originally a two-way typical American main street, Calle 8 was transformed in the late 60s into commuter highway. A few years later, the nearby Dolphin Expressway (I-836) was completed. Despite the opening of an elevated east-west speedway into downtown, Calle Ocho's prime stretch between 27th Avenue and I-95 was never converted back into the quaint main commercial core of Little Havana.

Plusurbia Design proposes to turn Calle 8 back to its original, main street self. The firm wants to calm traffic and widen sidewalks in the hopes of reversing 50 years of degraded neighborhoods and commerce left in the wake of a corridor turned freeway. PlusUrbia advocates for Calle Ocho as a destination, not as a pass-through corridor scarring one of the oldest, most authentic neighborhoods left in Miami.

The Florida Department of Transportation is currently studying the SW 7th and SW 8th Street corridors. Early Little Havana community meetings have shared FDOT scenarios that seem to be more concerned with vehicle movement than people movement. PlusUrbia, with strong ties to Little Havana, wants to unlock Calle 8's potential by proposing the restoration of the original two-way traffic. The Miami-based urban design firm has created images of a 21st century Calle Ocho with multimodal transportation alternatives such as dedicated bike and transit lanes, comfortable wide sidewalks and additional safe crosswalks in a vibrant urban setting.

More than 100 Little Havana stakeholders attended PlusUrbia’s October forum to share a vision for a better Calle Ocho. A diverse group of urban and transportation design experts worked interactively with the audience to empower the growing grass roots movement for calmed traffic and a better pedestrian experience on SW 7th and SW 8th streets. The overwhelming opinion of those in attendance, including three elected officials, is that Calle Ocho and SW 7th must be Complete Streets that serve pedestrians, cyclists and public transit equally with automobiles.

The long effort to turn public opinion in favor of Complete Streets has gained traction. In December, Miami Mayor Tomas Regalado wrote to the head of the Florida Department of Transportation urging that the Calle Ocho Corridor be redesigned as “complete street would serve residents, visitors, merchants, arts hubs and traffic with:

- Wide sidewalks, safe pedestrian crosswalks, retention of all on-street parking.

- Calmed traffic that eliminates the three-lane, one-way configuration that encourages speeding and dangerous driving that has resulted in pedestrian fatalities in each of the past several years.

- Enhanced public transit, transit stops and bicycle lanes (bikes could be on SW 7th or SW 9th)

- A redesign that gives equal priority to pedestrians, bicyclists, transit riders and commuters, recognizing Little Havana is one of the most important cultural destinations in South Florida.

From its office, on a bike lane footsteps from a commuter train station, PlusUrbia hopes to export its Calle Ocho campaign nationwide. The firm knows that democratic streets – that treat pedestrians, cyclists, transit riders and automobiles equally – will benefit every urban corridor in America: from the subtropics to Main Street USA.

(All photos used with permission from PlusUrbia)

ABOUT STEVE WRIGHT AND JUAN MULLERAT

Wright and Mullerat are part of PlusUrbia, a boutique urban and architectural design firm in Miami. Both live blocks from Miami’s Calle Ocho and have first-hand knowledge of the dangers of an urban corridor turned into a highway. Wright’s wife uses a wheelchair for mobility and Mullerat has two young daughters in strollers. Wright, PlusUrbia’s Communication’s Director, is a regular contributor to CEOs for Cities and other urban blogs. Mullerat is an award-wining urban designer who has created walkable neighborhoods around the world.