Understanding Growth, Part 3

"The debate on GDP growth frequently tends to be nonsensical. GDP growth can simply be influenced with the help of debt (and either through fiscal policy in the form of deficits or budget surpluses) or through the help of interest rates (monetary policy). So what sense do GDP growth statistics make in a situation with a several times larger deficit in its background? What sense does it make to measure riches if I have borrowed to acquire them?"

- Thomas Sedlacek in Economics of Good and Evil

Common consensus among our intellectual class is that debt doesn't matter. Perhaps more precisely: concerns over debt are less important than concerns over growth. Paul Krugman, the living caricature of this mindset, writing in his book End This Depression Now, made the following argument in the introduction:

Every time I read some academic or opinion article discussing what we should be doing to prevent future financial crises—and I read many such articles—I get a bit impatient. Yes, it’s a worthy question, but since we have yet to recover from the last crisis, shouldn’t achieving recovery be our first priority?

He then goes on to lament that GDP growth, "is barely above its precrisis peak," a clear sign that we are in a depression. Krugman has argued that more debt is a moral imperative -- debt is good and nobody understands debt (except him) -- that we're not grasping the basic lessons of John Maynard Keynes when we contemplate policies of fiscal austerity.

When everyone suddenly decided that debt levels were too high, debtors were forced to spend less, but creditors weren’t willing to spend more, and the result has been a depression—not a Great Depression, but a depression all the same.

Czech economist Tomas Sedlacek, whose book Economics of Good and Evil we are discussing this week, calls our current growth economy "Bastard Keynesian". He points to the story from Genesis of Joseph interpreting Pharaoh's dream as the first macro-economic forecast, a forerunner of Keynesianism. In the story, Pharaoh has a dream of seven fat cows grazing who are then consumed by seven lean cows. In a subsequent dream, Pharaoh see seven heads of healthy grain devoured by seven thin and withered heads of grain. When none of Pharaoh's magicians or wise men could adequately explain the meaning, Joseph was summoned. He told Pharaoh:

God has shown Pharaoh what he is about to do. Seven years of great abundance are coming throughout the land of Egypt, but seven years of famine will follow them. Then all the abundance in Egypt will be forgotten, and the famine will ravage the land. The abundance in the land will not be remembered, because the famine that follows it will be so severe.

Joseph then provided a way to deal with this crisis, one that would require prudence and sacrifice during the good years:

Let Pharaoh appoint commissioners over the land to take a fifth of the harvest of Egypt during the seven years of abundance. They should collect all the food of these good years that are coming and store up the grain under the authority of Pharaoh, to be kept in the cities for food. This food should be held in reserve for the country, to be used during the seven years of famine that will come upon Egypt, so that the country may not be ruined by the famine.”

The is the essence of Keynes. During the good years we save so that, during the difficult years, we can spend. One of his great insights is the paradox of thrift: when everyone cuts back on spending, as tends to happen during economic downturns, it only makes the crisis worse. In response, Keynes suggests that government can -- and should, like Pharaoh -- step in to build up reserves during good times so that, in those inevitable downturns, it can fill the gap and prevent unnecessary suffering.

What happens when Pharaoh wants more growth during the good years -- because growth is a good unto itself and more is always better/necessary -- and also wants to be able to counteract downturn during the lean years? That is where our growth economy operates now, which is why Sedlacek calls it Bastard Keynesian. It takes one half -- spending during downturns -- while doing little in the way of prudence to build up reserves during the good years.

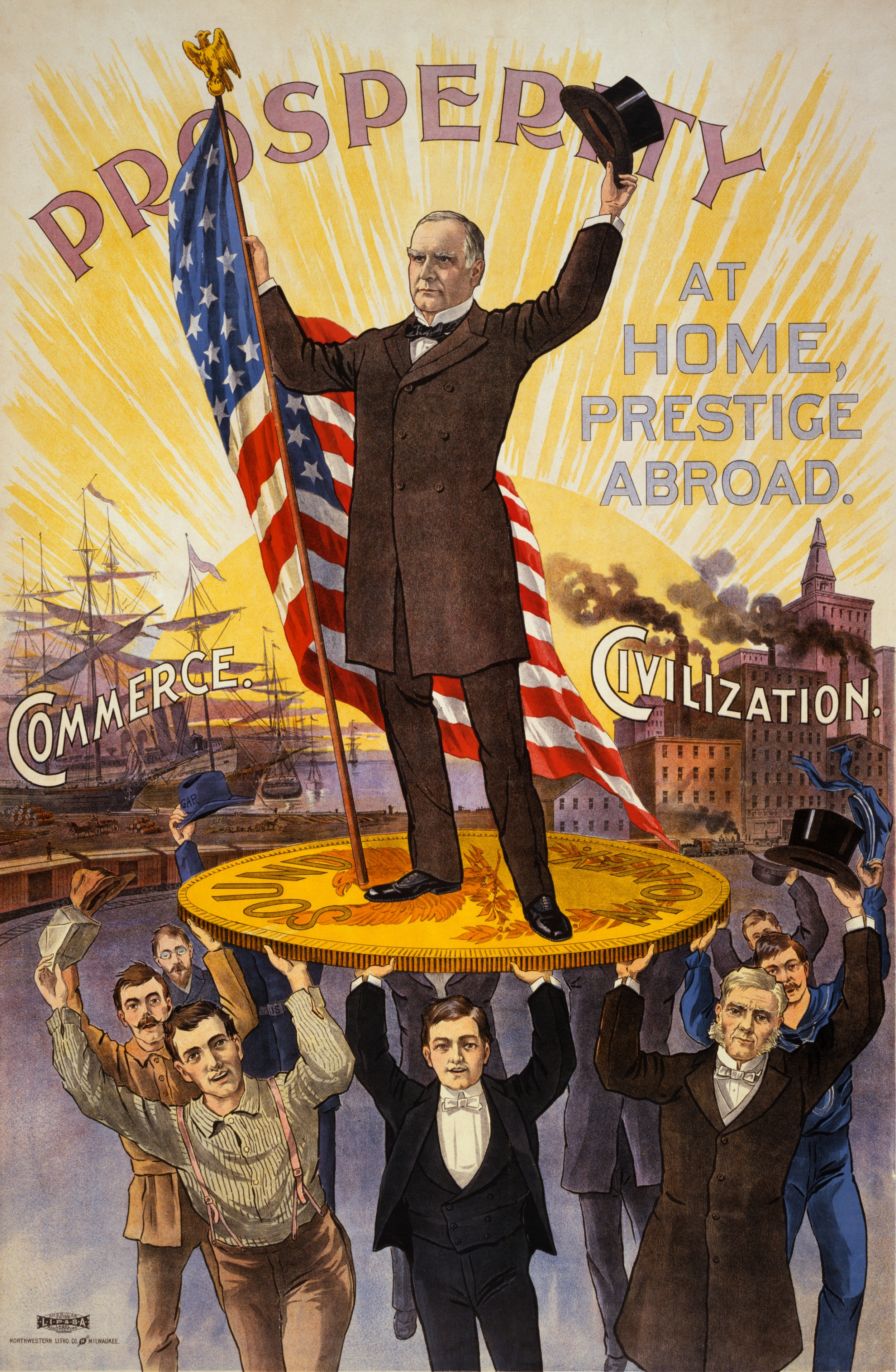

President McKinley campaigning on the barbarous relic, the gold standard. Image from Wikipedia.

This has turned our growth economy into a debt economy. We cheer when the economy grows by 3% in a year even when our collective debt levels have risen by more than 3% of gdp. Nobody who borrows $10,000 believes themselves to be $10,000 richer, yet we manage our growth economy as if this is an actual reality.

In a manner that mainstream American economic thought reflexively laughs at -- think Ron Paul, the gold standard, and the original Tea Party emphasis on balanced budgets -- Sedlacek describes the way in which interest rates allow money to travel through time. From Economics of Good and Evil (emphasis mine):

Money can also travel through time. This time-travel of money is possible precisely because of interest. Because money is an abstract construct, it is not bound by matter, space, or even time. All you need is a word, possibly written, or even a verbal promise, “Start it, I’ll pay it,” and you can start to build a skyscraper in Dubai.

Understandably, banknotes and coins cannot travel through time. But they are only symbols, a materialization, an embodiment or incarnation of that energy. Due to this characteristic, we can energy-strip the future to the benefit of the present. Debt can transfer energy from the future to the present.

On the other hand, saving can accumulate energy from the past and send it to the present. Fiscal and monetary policy is no different than managing this energy.

We will soon have experienced a decade of interest rates at or near zero. Understand what that is. It is a desperate attempt to energy strip as much of our future productivity as possible for the benefit of today. Negative interest rates, as are now being contemplated, would allow us to reach just a little bit further into the future. We are buying growth and the price we pay is our future stability.

Let me put some numbers to this abstract notion of lost stability. Back in 2013, we began to suffer through the horrors of the sequester. The sequester is an $85 billion reduction in spending on a $3.5 trillion federal budget, something Paul Krugman called a Doomsday Machine, but we can well imagine Pharaoh calling a prudent move. Nonetheless, consider that, with our unprecedentedly low interest rates, over the past decade we've been able to expand our national debt to nearly $19 trillion without increasing our annual debt service costs. At this point, for every 1% rise in interest rates, we are facing an additional $190 billion in interest expense -- more than double the Doomsday Machine of the sequester -- just to pay interest on our past spending.

How much stability do we have if our policymakers can't raise interest rates without exploding the budget? Ah, but Chuck, inflation is low. Yes, but if you Krugmanites are successful in your theory -- and how can you not be if the theory is to print and borrow endless sums of money until we get acceptable levels of spending back -- then inflation will rise and you will be forced to pick your cyanide. Destroy people's lives -- especially the poor -- through relentlessly rising prices or blow up the growth economy and suffer through the collapse. My guess is we'll try to stick it to the poor, but really, all bets should be off at this point.

As Sedlacek contends: "It's not a question of austerity: yes or no, but when." I've set the following video to the section where he discusses debt. Take particular note of how he suggests that Keynes today would be considered an extreme right wing thinker.

We have suffered what Sedlacek calls a tragic subject/object reversal. We created a growth economy to serve us. Now we serve it.

Debt once served us. Now we serve it.

Tomorrow we'll start looking at the basis for a different economic approach, one that supports a nation of strong towns.

An annual tradition, here is Chuck Marohn’s list of favorite books that he read in 2024.