Jane Jacobs, an urban ecologist

Seth Zeren is a founding member of Strong Towns. In this piece, he discusses Jane Jacobs' thesis on the value of old buildings in today's cities.

A historic building melds into the fabric of a Milwaukee street

Like a lot of young planners, I was introduced to Jane Jacobs through a course reading list. We were assigned the first few chapters of The Death and Life of Great American Cities (a.k.a. the Bible for planners, or at least the Old Testament). You know: the chapters on eyes on the street, corner stores, sidewalk ballet, etc.—even the chapter on the uses of neighborhood parks, which a lot of urban designers and open space advocates could use a refresher on (particularly in light of this recent analysis from our friends at City Observatory).

At the time, I was in the process of transitioning from geoscientist to urban planner and I was immediately taken with the realization that Jacobs was doing and writing about ecology a little differently than Charles Darwin, E.O. Wilson, or my advisor. Geology and ecology, being the studies of big complicated systems, don’t lend themselves to lab experiment. A core of the disciplines is the observation of natural systems and the testing of hypotheses with natural experiments. Jacobs was doing just that in her work; Jacobs was an urban ecologist.

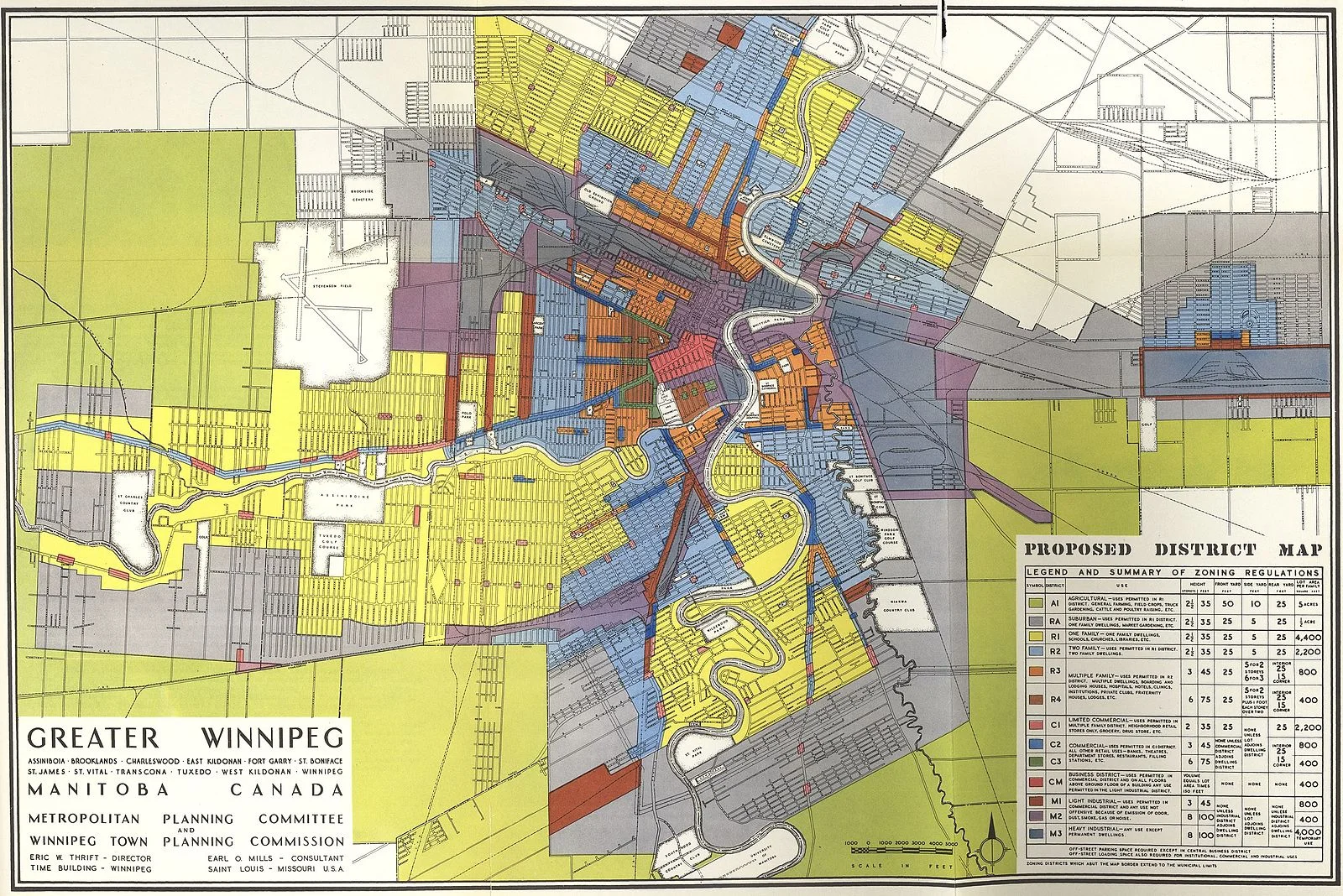

As a geologist, one of my favorite chapters in The Death and Life of Great American Cities was “The Need for Aged Buildings.” In the time of urban renewal and fight blight! Jacobs argued for the importance of a diverse building stock that includes maintaining old buildings along with the new. The essential insight:

If a city has only new buildings, the enterprises that can exit there are automatically limited to those that can support the high costs of new construction”—meaning “high profit or well subsidized.

Jacobs used the word “aged” deliberately; a beautifully restored historic building is essentially new again, with expensive capital costs that must be recouped in rent or subsidy. Aged buildings are less expensive to occupy than new buildings; therefore a diversity of building ages is a base condition for a diversity of uses, incomes, employment, etc. This is particularly important for the creation of new ideas and innovations and for creating organic opportunities for creating wealth. Here’s a-another excellent quote from this chapter: “Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings.”

Jacobs then highlights the particular example of how a building can have many lives:

Consider the history of the no-yield space that has recently been rehabilitated by the Arts in Louisville Association as a theater, music room, art gallery, library, bar and restaurant. It started life as a fashionable athletic club, outlived that, and became a school, then the stable of a dairy company, then a riding school, then a finishing and dancing school, another athletic club, an artist’s studio, a school again, a blacksmith, a factory, a warehouse, and now it is a flourishing center of the arts. Who could anticipate or provide for such a succession of hopes and schemes? Only an unimaginative man would think he could; only an arrogant man would want to.”

Central to her point, and the overall vision of the book, is the need for humility in design, planning, and development. Lately I’ve been referring to this as the need for incompleteness; leaving open the idea that the city is never “finished” and that we must leave space for others and future generations to iterate on top of our work today. Call it the doctrine of Incomplete Urbanism.

A mix of modern and historic buildings, put to use in Grinnell, IA

To Jacobs, a successful urban district has a mix of new and aged buildings, with buildings slowly declining as others are renovated or replaced, so that there is always a good diversity.

But the problem with aged buildings is that they can’t be created new, they are a “raw material”. If you don’t have any now, you have to build some new buildings and then wait 50-100 years for them to depreciate. In that sense they are like a non-renewable resource (or a slowly renewable one). We should be watchful of the overall balance of ‘shiny and new’ and ‘old and blighted.’

Jacobs, writing at the time of urban renewal was particularly concerned with “slum clearance” and large scale redevelopment plans:

Large swatches of construction built at one time are inherently inefficient for sheltering wide ranges of cultural, population, and business diversity. [...]

These neighborhoods show a strange inability to update itself, enliven itself, repair itself, or to be sought after, out of choice, by a new generation. It is dead. Actually it was dead from birth, but nobody noticed this much until the corpse began to smell.

The implications of these observations for planning and development are huge. A healthy neighborhood is like a forest, while a master planned community is like a field of corn. This ecological perspective on the built environment means that neighborhoods must continually change, bit by bit, year to year. Faster or slower rates of change should indicate a potential problem. For areas in need of redevelopment, the only way to return to a healthy urban fabric is incrementally, a few small projects a year, for 25+ years until the neighborhood has buildings of every age and condition, suitable for adaptation to the particular needs of some future time.

The practical implication for economic development is that old, nonconforming, grandfathered buildings are particularly important today because our building regulations make it even more difficult to build inexpensive structures new. In order to restore a healthy business ecology to our cities and towns, we need to find ways to work with planning, building, fire, utilities, ADA and other public regulators to ensure that these buildings can continue to be used or be incrementally reinvested.

Architects look at the city as a piece of art, a sculpture to be crafted in an open field. Engineers and technocrats look at the city as a machine to be tuned and upgraded. Planners and developers look at the city as a board game, writing rules to make things fair, or playing the game to see who can make the most money.

All of these models suffer from the sense that the city (or building) can be finished, optimized, perfected. They don’t look at the place over time. They assume a small number of creators and large number of consumers. They are not ecological. When you find yourself talking past a conscientious citizen in your community who seems to be arguing for nonsensical positions, ask yourself to which model of the city they are consciously or subconsciously subscribing.

Strong Towns’ model of the city is different. It is ecological. We know that cities are complex and hard to predict. They have many actors and they evolve in response to stress and forces. In this way, they become antifragile. Let's recognize the true complexity of our urban ecosystems and start building Strong Towns.

(Top photo by Rob Bye. All others by Rachel Quednau)

Related stories

About the Author

Seth Zeren is a recovering urban planner now working as a real estate developer on mixed-use infill redevelopment. He has been a member of the strong towns community since 2013. Seth's background is in climate science, ecology, evolution, and complex systems. He is passionate about the ecology and ethics of living in cities and towns, particularly the revival of small cities. He recently moved from the Cambridge, MA, to Providence, RI, to pursue incremental development in a smaller pond.