The Democratized Economy: Big Boxes, Urban Centers and Placemaking

Today we welcome back guest writer and member, Alexander Dukes. The first article in his Democratized Economy series, “The Emerging Democratized Economy,” defined the Democratized Economy, and the Modernist Economy. For background, here are brief definitions of each term:

“The Democratized Economy is an economy in which there are many small-scale owners of the means of production with local or regional influence. ”

The Modernist Economy is an economy in which there are a few, powerful owners of the means of production with national influence. The ideology of the Modernist Economy applies dogma such as “the one best way” and “form follows function” to mass produce standardized goods and services that adequately serve consumers irrespective of geography.

The Democratized Economy is an economy in which there are many small-scale owners of the means of production with local or regional influence. The ideology of the Democratized Economy promotes an inclusive culture of entrepreneurship that encourages broad, diverse swaths of the public to produce goods and services that are contextually responsive to local and regional needs.

The Big Box Status Quo

The great modernist architect Le Corbusier once declared that “A house is a machine for living.” No other quote better summarizes the modernist building pattern of the latter half of the 20th Century. Le Corbusier’s machine concept could be applied to any urban planning purpose, and was. Virtually all cities in the United States took the machine concept to heart after World War II, establishing land use “zones” which mechanistically dedicated land to singular uses. Retail zones are “machines for buying and selling products.” Business zones are “machines for professional office work.” Residential zones are “machines for domestic life.” Industrial zones are “machines for the production and extraction of goods.”

Rigidly zoning land in this way disperses city assets to such an extent that the use of an automobile is the only practical way to fulfill a person’s daily needs. Big box retail thrives in this environment. People living in these zones must drive miles back and forth from their home in residential zone to their workplace in the industrial or office zone. When these people need to shop for groceries, they rarely patronize a downtown that hosts local businesses. For many people, big box shopping centers are simply located closer to their homes than the downtown core. Therefore, most people living in “modern” American cities are simply going to patronize a retail zone’s shopping center, where they can easily park their car and dutifully buy a week’s worth of groceries in the “one stop, shop” supercenter. (Read more about big box stores from a Strong Towns angle.)

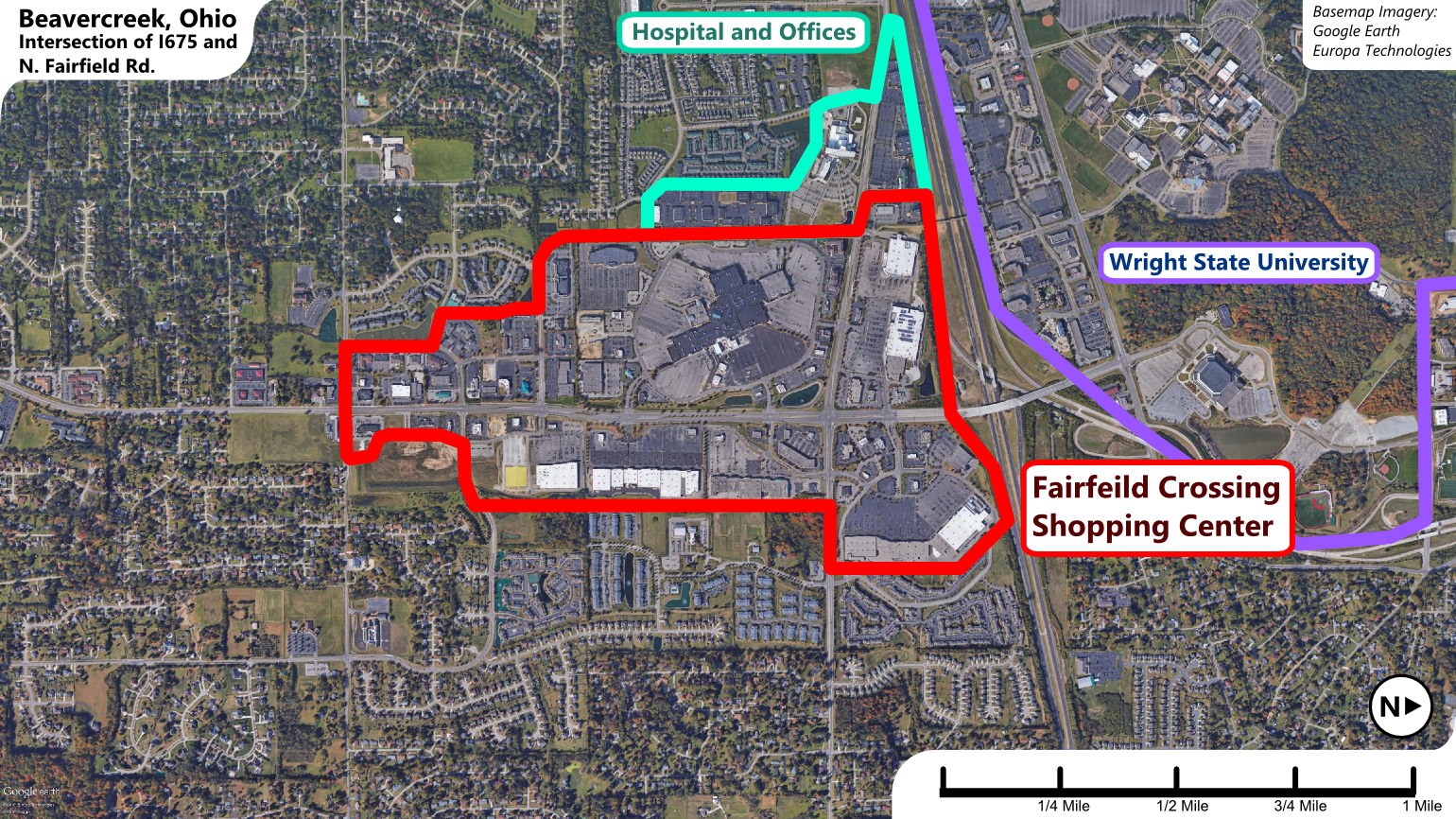

Beavercreek, Ohio’s Fairfield Crossing shopping center is a huge retail zone surrounded by office, university, and residential land use zones (virtually everything not outlined is a residential land use). Comfortably traversing the distances between these huge zones requires the use of an automobile. (Image from Google Maps with contextual overlay by Alexander Dukes)

The intersection of North Fairfield Road and Pentagon Boulevard is the primary intersection within the Fairfield Crossing shopping center. The space is designed solely to satisfy the needs of automobiles. (Image from Google Earth)

Just in case some brave pedestrian didn’t get the message; Fairfield Crossing is for cars. (Photo by Derrick Burke)

The effect of modernist zoning on the shopping habits of a city’s population is analogous to a stroad’s effect on street traffic. If you build stroads that encourage people to drive fast, you will get cookie-cutter, national franchise retail that people can comprehend when they’re driving through at 45+ miles per hour. City-wide, when your land uses are so spread out that no one has time to comprehend the nuance of local retail, your dominant retailers are going to be national big box establishments cloistered in shopping centers with two times the necessary parking.

When communities encourage big box and franchise development, the majority of their retail economy becomes Modernist. The vast majority of profits big box retailers earn are invested outside of the local communities their profits derive from. Literally, money is flowing out of local communities into the hands of a wealthy few with no ties to the region. By definition, a Modernist Economy seeks to “serve consumers irrespective of geography.” Therefore, why should big box retailers concern themselves with the health of a local economy? The answer is that they don’t.

It is more productive for communities to adopt a retail strategy that produces as many local retailers as possible, rather than catering to the needs of a few big box retailers. The local retailers that comprise a Democratized Economy spend most of the profits they earn in their local community. However, for people to shop locally there needs to be a pattern of development that is conducive to the nature of local retailers. Single use zoning (for all the aforementioned reasons) encourages big box development. Rather than a pattern of development that encourages the rapid automobile egress from zone to zone, our cities need a building pattern that encourages the full enjoyment of a holistic environment where people satisfy their daily needs by walking.

In New York City’s Chinatown foods can be sold from the sidewalk. Note how the pedestrians’ eyes are drawn to the produce. (Photo by Alexander Dukes)

Big box chains spend millions to achieve the same advertising effect these local retailers gain from the humble sidewalk. Also note how densely land uses are mixed in Chinatown compared to Beavercreek, Ohio. (Photo by Alexander Dukes)

Getting people to walk is critical to encouraging growth in local retail. People tend to shop locally when they can walk alongside a store window, see the product they want inside, and walk into the store on a whim. (If you doubt this, think about how you shop inside a mall.) It’s also easier for stores to advertise when people are walking. No need for massive signs to be read at 45 mph and up; most stores in walkable areas can attract sufficient business simply from the sign on their façade.

So how can communities create places that help local retail flourish? Creating walkable places that are conducive to local retail requires an understanding of something called placemaking.

Urban Centers and Placemaking as a Solution to the Big Box

Placemaking is the art of planning and designing environments to accommodate people in such a way that they just want to be there as part of their day. People don’t need an organized event to occupy good urban environments. Rather, well-designed urban environments are occupied through the natural, spontaneous human impulse to be social.

Placemaking is a hyper-local approach to developing space for a variety of land uses that are contextual to the local urban environment. To be a placemaker, you don’t have to be an architect or urban designer — although those professionals can (and should) be good placemakers too. Rather, you just need to be a good community steward that is active and knowledgeable about how the built environment affects your community.

High Street in downtown Mount Holly, New Jersey is full of local retailers in a walkable and compact built environment that people are naturally drawn to. (Photo by Alexander Dukes)

To weave the art of placemaking into the fabric of the city, there must be discrete places in which the placemakers focus their efforts. Because the modern American city is so dispersed between land use zones, I believe placemakers should look to create “nodes of activity” in the existing city structure that will serve as good urban environments. For the purposes of this series, I will call these nodes “urban centers.”

Urban Centers are compact, connected, and walkable places within cities where there is an intensification of human activity of all kinds, whether that activity is residential, office based, manufacturing, commercial, recreational, or educational. Urban centers are not “islands” of good development that are partitioned by walls, gates, or buffers that separate them from the wider community. Rather, urban centers should harmoniously integrate their land uses and physical attributes into the wider space around the urban center.

To achieve this goal of having an intense mix of human activities while simultaneously being a place people want to occupy, I believe an urban center needs to meet three core criteria:

- A Walkable, Interconnected Street System

- A Compact mix of Land Uses

- Adjacency to Major Transportation Infrastructure

Creating an urban center that meets all three of these criteria will result in an urban environment that supports local retail.

America’s communities need to shift away from a big box, “form follows function” retail strategy to a local, placemaking retail strategy. One way to make this shift is to replace the concept of the shopping center with the concept of the urban center. When placemaking urban centers become the default method of creating space for retail in a community, local retailers flourish and a broad, diverse Democratized Economy emerges.

In the final article in this series, I'll discuss specific ideas for placemaking an urban center.

(Top photo by Alexander Dukes)

Related stories

About the Author

Alexander Dukes is a United States Air Force Community Planner working at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey. He is a graduate of Tuskegee University and Auburn University, with a Bachelor’s Political Science and a Master’s in Community Planning, respectively. With this background, Alexander focuses his planning work on both urban public policy and the design of the physical realm for both military and civilian applications. Alexander is principally concerned with building sustainable cities, towns, and neighborhoods that provide all citizens- regardless of income or ethnicity, with access to meaningful employment, civic resources, and beautiful places.

A Japanese study is the first to quantitatively measure the economic impact of tactical urbanism. Spoiler alert: it’s good for business.