A Utah Republican Might have the Best Urban Transportation Plan

More than three years ago, Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah, along with Republican Representative Tom Graves of Georgia, proposed legislation called the Transportation Empowerment Act. As legislation goes, it was a near total failure. It died in committee and, from all reports, was never taken seriously outside of a small group of supporters. It made a good foil for those wanting the federal government to spend more on transportation (a big pot of money).

The Act proposed to reduce the federal gas tax from 18.4 cents per gallon to 3.7 cents (diesel would go from 24.3 cents to 5.0 cents), phasing that change in over a five year period of time. That sounds crazy -- after all, we're already spending more on transportation than we collect in gas tax and have been for some time -- but the catch is that the Act would also reduce the federal role.

The key provision of the Transportation Empowerment Act is the devolution of the federal responsibility from funding, guiding and directing national transportation investments to one thing: maintaining the interstate system. Period.

I'm going to say right off the bat that I think the reasons for this legislation are pretty messed up. I also think that it won't actually have the effect the Act's supporters think it will. Still, I think it's an idea that, given the political makeup of Congress and the state legislatures, provides the best path to achieving an urban transportation revolution, one that will help our cities become financially strong and resilient.

Dubious Logic

In announcing the Transportation Empowerment Act, Senator Lee displayed the standard confusion many conservatives in this country have regarding transportation. From his website:

The federal government also needs to open up America’s transportation system to diversity and experimentation, so that Americans can spend more time with their families in more affordable homes, and less time stuck in maddening traffic.

House-hunting middle class families today often face a Catch-22. They can stretch their finances to near bankruptcy to afford a home close to work. Or they can choose a home in a more affordable neighborhood so far away from work that they miss soccer games, piano recitals, and family dinner while stuck in gridlocked traffic.

This is where the confusion starts. We need diversity and experimentation -- yes -- but it's one dimensional: fighting traffic congestion. He makes the very true argument that location has value and that our many decades of federal transportation investments force families to confront a bad set of choices: either pay lots of money to be near things or live far away and spend your time and money on commuting. Then, he starts down the path to confronting the distorted land use paradigm. Again, from his site:

The solution is not more government-subsidized mortgages or housing programs.

Agreed. The dots are all there to be connected -- location creates value, government housing programs mess with housing markets, families are hurt by all of this -- but then the narrative spins off into conservative socialism:

A real solution involves building more roads. More roads, bridges, lanes, and mass-transit systems. Properly planned and located, these projects would help create new jobs, new communities, more affordable homes, shorter commuting times, and greater opportunity for businesses and families.

Transportation infrastructure is one of the things government is supposed to do – and conservatives should make sure it is done exceptionally well. Unfortunately, since completing the Interstate Highway System decades ago, the federal government has gotten pretty bad at maintaining and improving our nation’s transportation infrastructure.

“If we cut the middleman — the federal government — out of the equation, there will be less distance between the sources of transportation revenue and the projects being proposed, and thus, a greater natural incentive to seek projects that financially pay off.”

Build. Build. Build. Build. Build. That's the story.

Senator Lee's theory is that, if we cut the middleman -- the federal government -- out of the equation, there will be less money wasted on bureaucracy and red tape, and more money available for actually building our way out of congestion. I think that theory is half-crazy, but let me restate it in a way that I think will actually get us somewhere: If we cut the middleman -- the federal government -- out of the equation, there will be less distance between the sources of transportation revenue and the projects being proposed and, thus, a greater natural incentive to seek projects that financially pay off.

And let me just reiterate: The projects that pay off, that actually generate a positive return on investment, have nothing to do with building roads, bridges and more lanes, and everything to do with making small, incremental investments in our existing neighborhoods.

Relentless Math

There are five rural congressional districts in the United States represented by Democrats -- I live in one -- and I'm not aware of any urban congressional districts represented by Republicans. In a very coarse sense, the country is split along rural/Republican and urban/Democratic lines. I'm not suggesting this is a good thing.

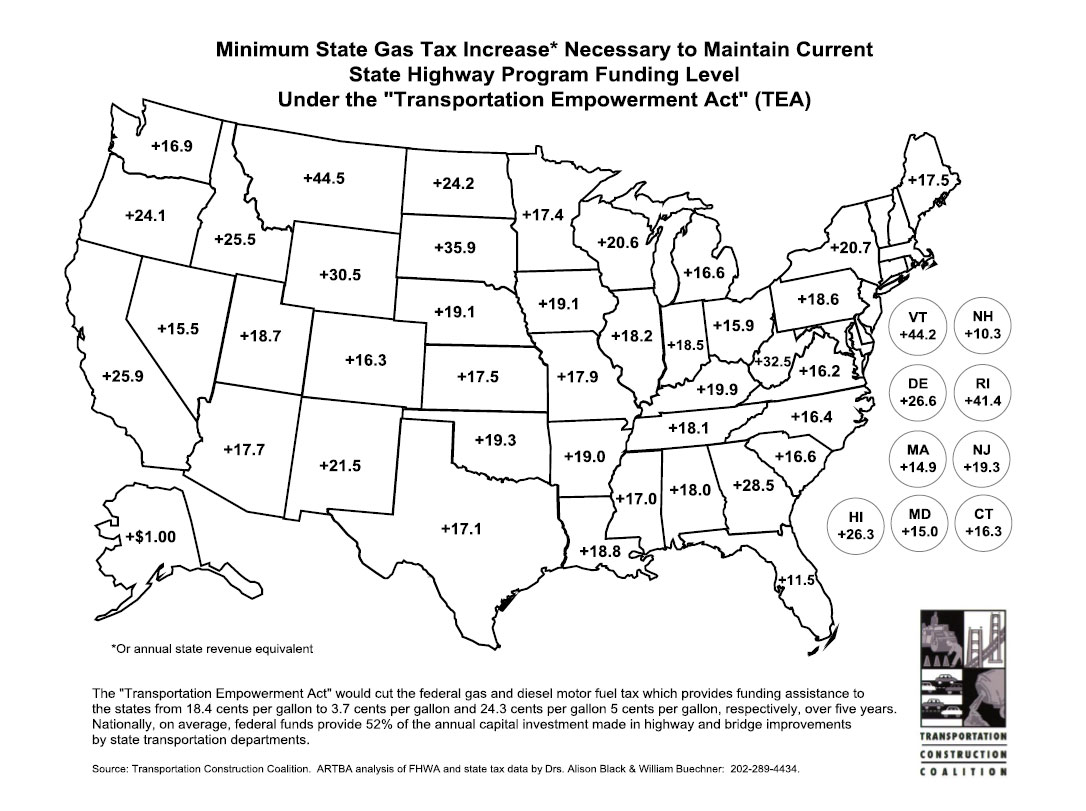

When the Transportation Empowerment Act was proposed, transportation lobbying groups reacted strongly in opposition of a reduced federal role. One group -- the Transportation Construction Coalition (guess what they support) -- put out a map that showed just how much each state would need to raise their state gas tax to make up for the loss of federal transportation spending. The numbers shown on the map are highly inflated -- it counts some one-time gimmicks in the federal contribution -- but even so, look at the distribution, particularly in regards to a rural/urban split.

Some of the losers in the Transportation Empowerment Act: Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, West Virginia, Georgia, Alaska.

Some of the winners in the Transportation Empowerment Act: Maryland, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Virginia.

When we delve deeper into each state, we can see things even more clearly. Here's a map of the flow of transportation revenue in my home state of Minnesota. Contrary to what many in rural America believe, money flows from urban areas to suburban and rural areas. There is a huge net subsidy of suburban and rural living from the tremendous financial productivity of urban areas.

Let me summarize: In a very coarse sense, federal transportation dollars flow from blue-leaning states with more urban dominance to red-leaning states with more suburban/rural dominance while state transportation dollars tend to flow from blue-leaning urban areas to red-leaning suburban/rural areas.

And we have a red state senator and a red state representative pushing a transportation funding bill that would end the largest of those transfers.

Where Will Innovation Happen?

Outside of the lobbyists and vested interests trying to continually expand the trough at which they feed, there are two primary arguments against the Transportation Empowerment Act.

The first is an equity argument: We owe it to states like Wyoming and Georgia to ensure that they have high quality transportation systems. My response to that is simple: (1) We already do with the interstate system, which will be maintained even better with a more focused federal approach, and (2) the evidence is that federal transportation spending -- especially that outside of interstate maintenance -- is actually making us poorer. If we want to help people, there are many better ways to do it than transportation spending.

I want to spend more time with the second argument, which I think has greater validity: If we want innovation in transportation, state DOT's, along with county/regional transportation entities, are the least progressive actors on the stage today. The federal government is trying to do innovative things. Taking them out of the loop and giving that money to states is going to take us backward.

Let's be clear about how the federal government innovates. In government, new ideas are a threat to all existing programs. The only way new ideas happen is if they add to, not replace, existing systems. So we are spending $1 on highways and want to innovate by spending $0.10 on transit. That means we need to spend $1.10 (likely $1.20 as in $1 for highways, $0.10 for transit and a $0.10 highway sweetener to get the bill passed). So federal innovation never involves shifting money away from destructive practices -- the kind of innovation we desperately need when it comes to transportation -- but instead it means trying to counteract bad spending with smaller levels of targeted good spending.

This is the approach that has given us transit systems that follow the 1960's commuter model and the provide-marginal-service-to-the-poor model but nothing predicated on broadly building wealth in our communities. We get complete streets (separate but equal), Safe Routes to School (instead of schools on safe routes) and TIGER (local indebtedness initiative) as innovations. I'm not inspired.

Plus, we have to confront the hard reality of who is in charge right now. I'm not a hyper-partisan, but I can count. It looks like the transportation bill that will soon be on offer is going to be long on the worst kind of highway-, bridge- and interchange-funding -- perhaps even partially privatized -- and short on anything that anyone reading this piece is likely to call innovation. Give me a choice between that federal approach and taking my chances with the fifty states, and I'll hedge my bets. I know we can win in some and, when we do, create a model for others to follow as they get into more and more trouble with the standard approach.

But who says we have to give all the money to the states?

A BiPartisan Compromise

As we've interviewed thought leaders for our Infrastructure Crisis series, one thought continues to come to the fore: We should be giving transportation money directly to mayors. With no strings.

Part of the Transportation Empowerment Act was a phase-out of federal funding where the transition money was given as a block grant directly to the states. What if instead, as a way to generate a real bipartisan consensus in Congress as well as across the country, we gave a decent percentage of that transition money directly to our major cities? If we really want to drive innovation, that is where it will happen.

Funding for the interstate system was supposed to end in 1972. We were essentially done building the system by that time—a few stubborn segments, mostly in places that shouldn't have been built—were all that remained. Of course, it didn't end; we have continued to expand the system ever since. A surge in federal infrastructure spending right now is going to invest in the worst possible projects and, in the process, stifle innovation, make our cities poorer and set us back many years.

It's time to seriously consider alternatives to the big pot of federal money.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.