Who Pays for Growth in Collier County, Florida: Part 1

In 1911, Memphis-born advertising magnate Barron Collier fell in love with Southwest Florida. Following a vacation to Fort Myers, Collier set his sights on the large-scale development of what was then—before the age of either air conditioning or mosquito control—a vast and inhospitable wilderness. Within two decades, he was Florida's largest landowner, controlling over one million acres. Collier helped channelize and drain parts of the Everglades and built the Tamiami Trail, the first road connecting the Gulf Coast to Miami. For his efforts, Collier County, the largest in Florida by land area, was named in his honor.

Advertising magnate Barron Collier. Image via WikiCommons.

A century on, Florida is unrecognizable, but Collier's descendants still dominate the business of large-scale land development in Collier County, which is best known nationally for the affluent beach community of Naples. As of this writing, a series of three master-planned communities proposed by Collier Enterprises, slated for over 8,000 new homes, looks to dramatically reshape the future of the region.

The proposed communities, unfortunately, are also entirely the wrong kind of business as usual. Detailed fiscal analysis by experts, including Urban3, demonstrates that they will generate hundreds of millions of dollars in long-term costs to county taxpayers, far exceeding the revenue they create.

To approve these projects will mean doubling down on an automobile-centric suburban growth model that has already saddled Collier County with mounting infrastructure needs and budgetary shortfalls. It will also mean decisively extending this pattern of development into the county's rural interior, brushing up against fragile wetlands and the habitat of endangered species, most notably the Florida panther. In doing so, it will foreclose upon an opportunity to demonstrate a stronger way for one of America's fastest-growing regions to grow, one that actually produces more true prosperity than it destroys in the long run.

As of this writing, one of the three communities, Rivergrass, was approved in early 2020 by a 3-2 vote and has since been subject to litigation. The Conservancy of Southwest Florida sued Collier County, alleging that Rivergrass’s approval violates multiple county ordinances. In May 2021, a state district court judge ruled in favor of the county after refusing to hear several entire categories of evidence. The Conservancy intends to appeal the ruling.

The other two villages, Longwater and Bellmar, have been recommended for approval by the Planning Commission and will go before the County Commission for a vote on May 25th, 2021. [Update as of June 2nd: The hearing concluded without a vote, and the issue will be discussed again at the County Commission meaning on June 8th.] All three will also require federal environmental permits before construction can occur.

The story of these developments is the story of America's Growth Ponzi Scheme in miniature. In a five-part series, I will use Collier County as a case study to show how insolvent growth persists in Florida. How it persists is most often in plain sight. It's based on a willingness by elected officials and their appointees, whose job is to oversee and guide the region's development, to say one thing and do another, and to bend the spirit, intent, and plain language of their own policies to the point of near meaninglessness.

Collier County needs to find a better way to grow.

Here is an outline of the series I’ll be sharing on Collier County. Read Part 1 below, and stay tuned for the rest of the articles as we release them.

Part 1: Where Did We Come From, and Where Are We Going?

Part 3: The Failure of Fiscal Neutrality for Water Infrastructure

Part 1: Where Did We Come From, and Where Are We Going?

The history of this part of Florida has always been tied to the grand, even megalomaniacal development schemes of outsized figures like Barron Collier. Channelizing and draining the Everglades in an attempt to tame it for agriculture, without grasping the complex and unique hydrology or ecology of the "River of Grass," was a decision whose enormously destructive ramifications would only later be understood.

Aerial photography shows the scattershot development pattern of Golden Gate Estates. Source: formulanone via Flickr.

In the postwar era, Southwest Florida was ground zero for giant speculative developments aimed this time at residential buyers. Companies bought enormous tracts of land, paved rudimentary street grids, platted hundreds of thousands of lots, and sold them to northern investors or would-be retirees, often sight unseen. I've written at length about these pre-platted developments, such as Lehigh Acres, before. Most now struggle with inadequate infrastructure, few jobs or amenities, incoherently scattered development, and cheap, low-quality housing.

In Collier County, the subdivide-and-sell land scheme du jour was Golden Gate Estates, and its aborted southern expansion, established in the 1960s by the con artists of the Gulf American Land Corporation. Located east of Naples, the area consists of 91 square miles—bigger than the city of Boston—of large residential lots with water wells and septic tanks. More than half of them were still vacant, along with three-quarters of all commercial centers, as of 2016.

The portion of Golden Gate Estates south of Interstate 75 is even stranger: nothing but a street grid and undeveloped scrubland. It's so desolate that, according to unbelievable-yet-somehow-true news reports, "[d]uring the 1980s, drug smugglers landed DC-3s on the long boulevards. A Cuban paramilitary group trained there until the early 1990s, burying a cache of ammunition that blew up in a forest fire."

The pattern here is that growth in Florida has always been a go-big-or-go-home proposition, and one in which the game is to reap the rewards early and leave the costs—financial and otherwise—to subsequent generations.

Many Floridians have long understood this, of course, and by the 1980s, the backlash against short-sighted development was so strong that the state pivoted to become a pioneer of new growth management practices. The 1985 state Growth Management Act required each county and city to adopt a local comprehensive plan compliant with state standards. Among other things, the local government had to proactively anticipate and seek to guide growth through the use of such tools as Future Land Use maps and Capital Improvement Plans, removing the "free for all" element that had allowed things like Golden Gate Estates.

In this era, Florida also pioneered policies designed explicitly to make growth "pay its own way." Development impact fees are more widely used in Florida than almost any other state, and concepts such as concurrency (requiring infrastructure be built out in tandem with the new development that will require it) are part of the planning lexicon.

Also ubiquitous in Florida, and central to our Collier County story, is the principle of fiscal neutrality, which holds that that new development should result in no net increase in costs borne by existing taxpayers for public services and infrastructure. (As we will see shortly, "fiscal neutrality" as actually implemented has about a million holes in it.)

The 1985 Growth Management Act, although it was effectively repealed in 2011, permanently launched the era of technocratic growth management in Florida. There is no longer any shortage of detailed planning for future development. Maps are drawn, costs and traffic flows are projected, interlocal agreements are signed, and special development funding districts are established.

The question is, does this maps-and-charts-and-consultants approach actually solve the problems of growth imposing massive costs on the next generation? The answer is a resounding "no," and Collier County's experience helps us understand why.

The Big Cypress National Preserve dominates the eastern half of Collier County. Source: US Department of the Interior via Flickr.

Meet the RLSA

A map of Collier County. The proposed three developments—Rivergrass, Longwater, and Bellmar—approximately comprise the red area near the center. Source: Google. Click to view larger.

Collier County's growth dynamics have been shaped by the free-for-all land rushes of previous generations. Most of the county's population lives in a narrow strip of land along the Gulf Coast, which is "built out" in the sense that there are no large undeveloped tracts left. Any growth there must come from redevelopment.

As you travel east, you soon reach Golden Gate Estates—a massive area which, although sparsely populated, consists of privately owned lots already spoken for—large-scale new development is mainly off the table here as well.

That leaves the areas farther east: agricultural lands toward Immokalee that produce fresh vegetables, tomatoes, and cattle, and, east and south of that, the vast Everglades-adjacent wetlands of the Big Cypress National Preserve and other federally protected areas.

Much of eastern Collier County (outside the preserves) is zoned to allow residential use at a density of one lot per five acres, similar to Golden Gate Estates. This is a very low density that requires septic systems (sewer service would be prohibitively expensive) and does not support significant commercial development—which means long drives to access basic needs. There is widespread recognition that to actually build out these areas in such a pattern would be environmentally and fiscally ruinous. Faced with pressure from the state government in the late 1990s to downzone eastern areas to one dwelling per 20 or 40 acres, Collier County reached a compromise, spurred in part by the lobbying of big developers, including Collier Enterprises. In 2002, the County passed a program called the Rural Land Stewardship Area program, or RLSA.

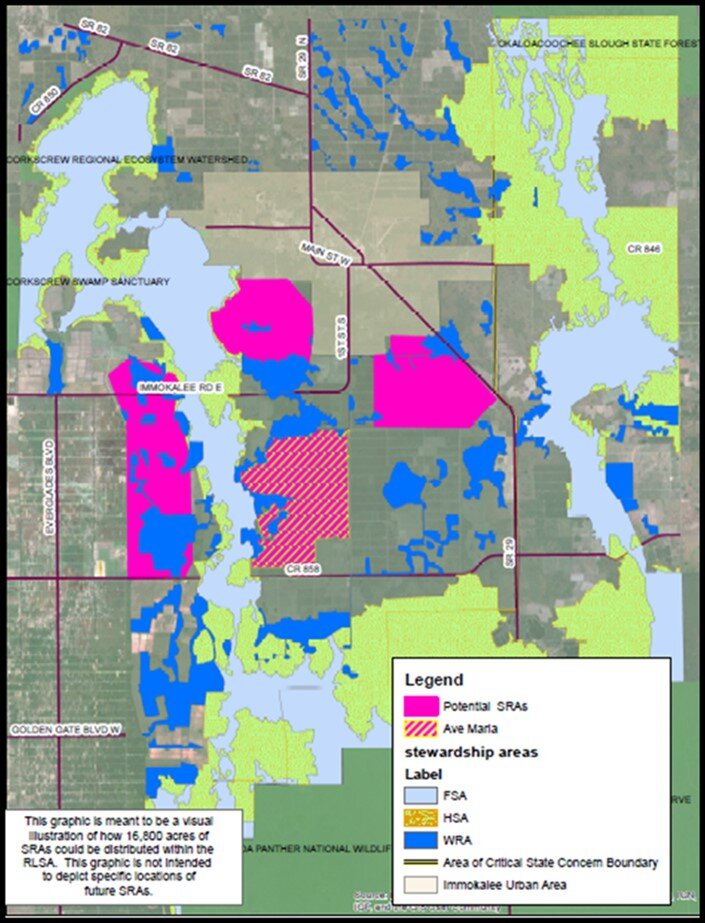

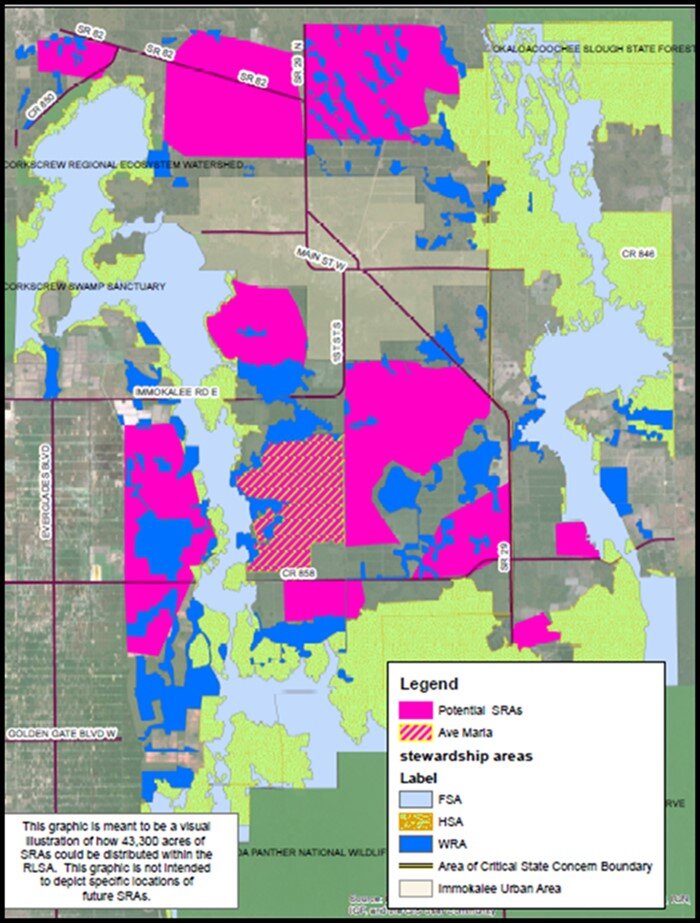

Collier County’s RLSA program designates “sending” areas (SSA) to be permanently protected from development, and "receiving” areas (SRA) where compact development can be concentrated using transferred development rights. Image via Collier County.

The SRA for Rivergrass is visible on this map; Longwater and Bellmar are to the south of Rivergrass, but are not depicted as they have not yet been approved for development.

The RLSA was described to me by Nicole Johnson of the Conservancy of Southwest Florida as a "TDR program on steroids." TDR stands for Transfer of Development Rights, and it works somewhat like a cap-and-trade program for carbon emissions. Owners of rural or wilderness land can sell their development rights, permanently forgoing the option to develop their land. The buyer of those rights receives a credit, allowing them to build at increased density on the buyer's own land. The transfer thus concentrates development into denser clusters (in Collier County these are called "villages" and "towns") while leaving the majority of the land rural.

Collier County is far from the only place in Florida or the rest of the nation with a TDR program, but here's the "steroids" part. Rather than a straightforward transfer of one dwelling unit for one unit, Collier County's RLSA program also allows landowners to obtain density bonuses for a variety of measures that ostensibly serve conservation objectives. These bonuses are called Stewardship Credits. At the eleventh hour before the RLSA’s adoption in 2002, two policy changes dramatically inflated the number of Stewardship Credits that could be generated through the program, with no chance to undergo careful scrutiny by either the public or county staff.

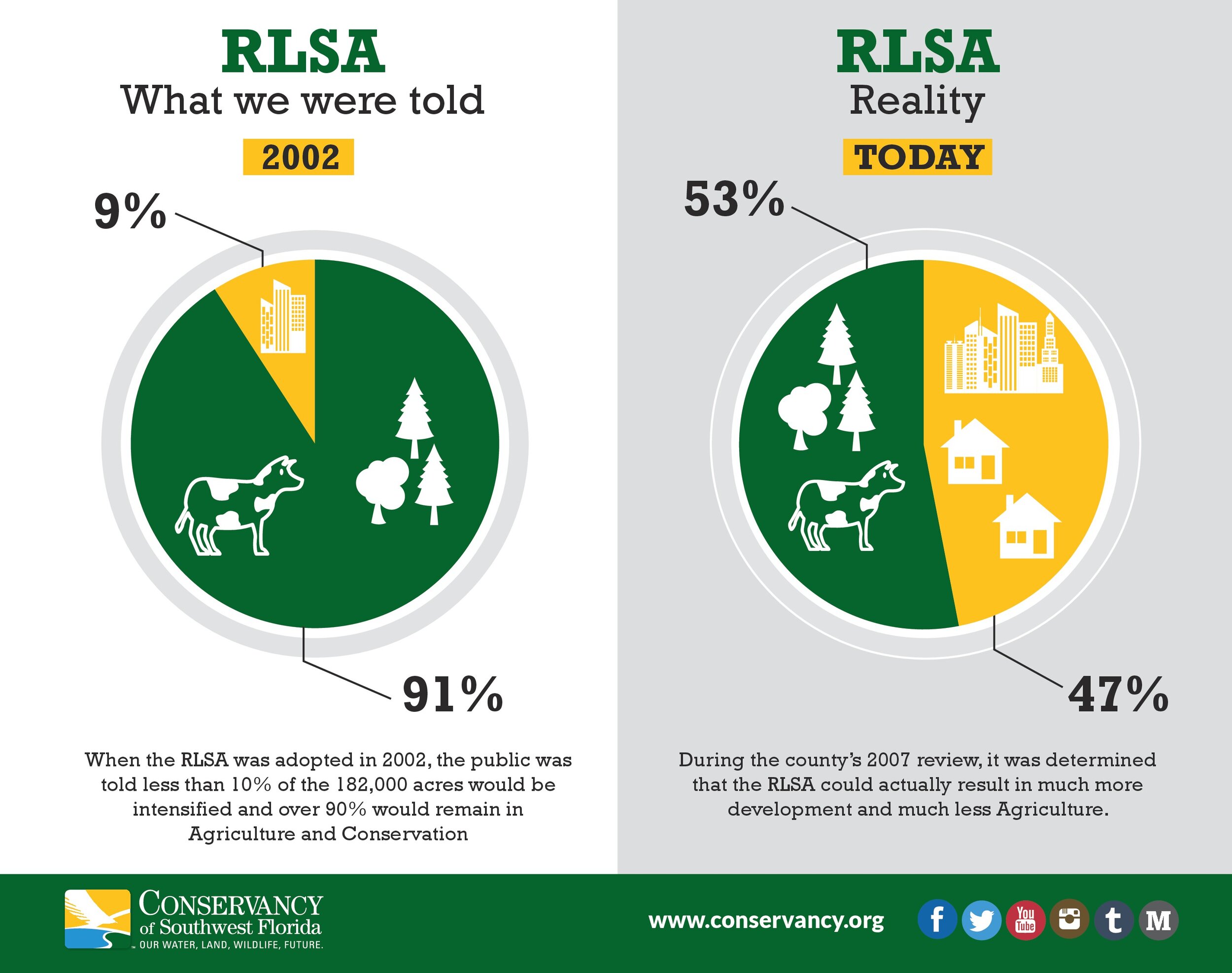

The result has been to dramatically increase the amount of development ultimately allowed in eastern Collier County, according to Johnson. The initial RLSA proposal would have, at build-out, allowed development on 9% of the participating rural land, or about 16,800 acres. The proposal that actually passed in 2002, following the last-minute changes, allows up to 43,300 acres, or 68 square miles, of development: an area comparable to that of Washington, D.C.

The only kind of development that can navigate the complex provisions of the RSLA is large-scale and master-planned. This is also encouraged by the fact that only eight property owners control 85% of the lands eligible for participation. The first large-scale use of the RLSA was for the master-planned community of Ave Maria, approved in 2004. The next salvo is this year's three closely linked proposals from Collier Enterprises. Assuming Rivergrass, Longwater, and Bellmar are all built, Collier Enterprises plans to retroactively merge the three "villages" into a "Town of Big Cypress" with over 10,000 homes on about 4,000 acres of land.

Rhetoric Versus Reality

The RLSA program, in principle, draws on the philosophy of New Urbanism and the recognition that compact, walkable development has the potential to conserve both money and precious land. Here is the way Policy 4.7.1 of the county’s official RLSA ordinance defines a “town.” Notice that it is laden with urbanist buzzwords (boldface emphasis mine).

Towns have urban level services and infrastructure that support development that is compact, mixed use, human scale, and provides a balance of land uses to reduce automobile trips and increase livability. Towns shall be not less than 1,000 acres or more than 4,000 acres and are comprised of several villages and/or neighborhoods that have individual identity and character. Towns shall have a mixed-use town center that will serve as a focal point for community facilities and support services. Towns shall be designed to encourage pedestrian and bicycle circulation by including an interconnected sidewalk and pathway system serving all residential neighborhoods.

In practice, unfortunately, the application of the RLSA framework to Collier Enterprises' plans is a case of lipstick on a pig. In this case, the promise of sustainable development to be achieved through TDRs allows the developers a veneer of fiscal and environmental sustainability and "good planning" while essentially delivering the same old, same old.

In the following installments of this series, we will break down all the ways in which this planned "town" falls far short of fiscal neutrality, threatens essential wildlife habitat, and ultimately makes an almost Orwellian mockery of the plain-English intent of the county's own growth management policies.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is also a founding member of the organization. His work at Strong Towns focuses on housing issues, small-scale and incremental development, urban design, and lowering the barriers to entry for people to participate in creating resilient and prosperous neighborhoods. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota, with a concentration in Housing and Community Development.

Daniel’s work with Strong Towns reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children.