Citizens Rally to Turn a Dangerous Stroad Into a Successful Community Hub

Huron Avenue

Editor's Note: Since publishing this article we've been contacted by Port Huron officials and are awaiting clarification on several details. The article will be updated as we confirm new information.

“Port Huron is a prewar city, so it has the bones of a strong town,” Tyler Moldovan told me. “But there’s a city plan from the 1960s that was never fully realized, and it has a death grip on this place.”

Moldovan is a resident of the Michigan city, which boasts 28,000 residents. He's a transit operator for Blue Water Area Transit, a homeowner and, by all appearances, a polymath. When the city announced plans to repave its main commercial thoroughfare, Huron Avenue, Moldovan saw a once-in-a-generation opportunity. The avenue has long lived a double life: It’s home to much of the city’s commerce and yet, at four lanes wide, it resembles a highway, whisking drivers right past those storefronts. Businesses chronically struggle on this stretch, and Moldovan believes this is partially because Huron Avenue is trying to be two things at once — a commerce-focused street and a transportation-focused road — and failing at doing either well. Consequently, it fails its small-business community the hardest.

Luckily, the Huron Avenue of today doesn’t have to be the Huron Avenue of tomorrow. In March, 413 residents wrote to the city council demanding street trees, mid-block crosswalks, wider sidewalks and a host of traffic-calming measures. “If nobody speaks up, we’ll just get the same road but with federally compliant ADA ramps,” Moldovan added.

He and his allies have long sparred with the city’s leaders over the benefits of narrower streets. “Nobody is listening,” he sighed. “Everyone is looking to the past and not at the present, least of all the future.”

This time, however, the city couldn’t look away. The 413 letters joined the city manager’s initiative to establish a task force in advance of the Huron Avenue repavement project. Set to meet twice a month until the design phase of the project begins, this task force is composed of a diverse group of residents, including representatives from the city, the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT), the community college and local charities. At their first meeting on April 22, 2024, the task force was joined via Zoom by property and business owners, as well as a group championing rights for the disabled. “All in all, this is definitely a win,” Moldovan said of the task force. “At least we’re having this conversation.”

Having everyone in the same room on Monday night also introduced an unlikely ally: MDOT. Having pioneered several “road diets,” the agency’s representatives not only appeared sympathetic to slimming Huron Avenue but also made a good case for it. Throughout the evening, MDOT illustrated that four-to-three-lane conversions were operationally safe, standard and even popular across the state. Moreover, the agency pointed out that narrowing the road would not contribute to congestion or endanger road users or local commerce.

Still, not everyone in the room was convinced of the benefits of narrower streets. Thoroughfares like Huron Avenue are often thought to be the economic artery of a small town, offering both visitors and residents a means of reaching and traversing a bustling downtown by car. To best serve this car travel, roads should be wide and parking plentiful. Otherwise, where will patrons park and how will they get there?

The reality is that half a dozen businesses have shuttered in the last two years alone, citing a lack of foot traffic. “And to think businesses pay a premium to operate on that avenue, ostensibly because of the built-in foot traffic and attractive location,” Moldovan added.

When it comes to the area’s reputation for safety, a statistic haunts the locals: 8%. According to the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, St. Clair County, home to Port Huron, witnessed an 8% fatality rate for bicyclists between 2010 and 2014. For comparison, Wayne County, which has nearly 10 times the population and is home to the Detroit metro area, has a 3% fatality rate for cyclists in the same period.

A heatmap from the Michigan Traffic Crash Facts data query tool shows that between 2004 and 2022, several segments of Huron Avenue have witnessed nearly a dozen injurious and fatal crashes. The same tool also illustrates how much property damage along the corridor can be attributed to crashes. In those same years, some blocks of Huron Avenue have experienced as many as 100 property-damaging crashes.

Moldovan, who is eager to become a parent, fears that if his children inherit the Huron Avenue of today, they’ll never get to enjoy the freedom of biking on the street. “If it’s not safe for a kid, is it safe at all?”

This heatmap showcases property damage caused by crashes between 2004 and 2022. The red pins indicate injurious and fatal crashes for the same period. Both were accessed via the Michigan Traffic Crash Facts query tool.

What Can a Narrower Street Do for You?

Still, it’s understandably hard to imagine how a narrower street could be safer and more productive. Across the country in California, Lancaster Boulevard’s story may offer inspiration. From March through November 2010, the city converted the five-lane arterial — a definitive stroad — to a two-lane street.

“The results have been nothing short of astonishing,” Amara Holstein said of Lancaster’s transformation in Build a Better Burb. “The nine-block stretch has completely rejuvenated downtown. People flood in for events, from farmers’ markets to holiday fests, or to go to 50 new shops, restaurants, and businesses that have since opened, along with a new park and museum. Cars don’t drive faster than 10 to 15 mph, and injury-related traffic collisions are down. Overall, the project has been estimated to have generated $273 million in economic output.”

Closer to home, businesses on Nine Mile Road credit lane narrowing with the neighborhood’s revival. "It was vacant and empty and there wasn't much going on," the city of Ferndale’s planning manager told Second Wave Media. “You could essentially fire a bowling ball down the middle of Nine Mile." Now, the Detroit street has become a “bustling commercial corridor … packed with shops, bars, restaurants, pedestrians, bikes, and cars,” according to the local news.

Across the border, Toronto’s success with outdoor patios in 2021 offers another argument in favor of foot traffic. Supplanting parking spaces with outdoor dining opportunities didn’t reduce business, as some feared. Instead, The Globe and Mail reported that residents spent a total of $181 million at curbside patios during the summer of 2021. If those spaces had remained dedicated to parking, only $3.7 million would have been reaped during the same period. In other words, curbside patios produced 49 times more revenue than parking fees would've earned.

In addition to creating economic booms, narrowing streets can help a city's finances by reducing its expenses. Wider streets cost more: “With multiple lanes and large signalized intersections, stroads are downright expensive to construct and they're typically built all at once, creating a hefty up-front cost for any city,” Strong Towns Program Director Rachel Quednau wrote in 2018. “Again, look at all that pavement. The costs of keeping stroads smooth, intersections functioning, etc. really add up as time goes on. And because they're frequently used by semi-trucks, they get even more wear and tear and need to be repaired sooner.”

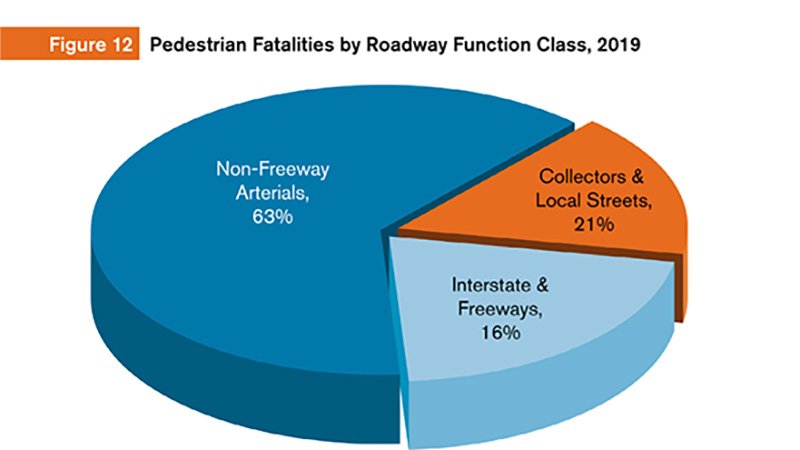

Possibly the most dire and chronically overlooked cost of wide roads is in the danger they induce. According to a May 2022 report by the Governors Highway Safety Association, non-freeway arterial roads like Huron Avenue continue to be the most dangerous for people on foot, accounting for at least 60% of all fatalities in 2020. A road that supports high speeds and multiple lanes while simultaneously encouraging pedestrian and bike traffic by providing sidewalks, ADA features and sharrows is deadly by design. Perhaps the deadliest.

For Moldovan, the urgency to change the status quo is there. “What we have now is clearly not working,” he noted. The last thing he wants to endure is months of discussion, design and construction only to be left with a stroad he’ll caution his future kids to avoid and a death toll that could’ve been prevented. Most importantly, he wants to see Port Huron thrive. He’s there for the long haul.

Are you ready to start making a difference in your town? Click below to find a local conversation near you!

Asia (pronounced “ah-sha”) Mieleszko serves as a Staff Writer for Strong Towns. A dilettante urbanist since adolescence, she's excited to convert a lifetime of ad-hoc volunteerism into a career. Her unconventional background includes directing a Ukrainian folk choir, pioneering synaesthetic performances, photographing festivals, designing websites, teaching, and ghostwriting. She can be found wherever Wi-Fi is reliable, typically along Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.