The Future of Land Use and Incremental Development

This article was originally published, in slightly different form, on the author’s Substack, The Post-Suburban Future. It is shared here with permission. The image was provided by the author.

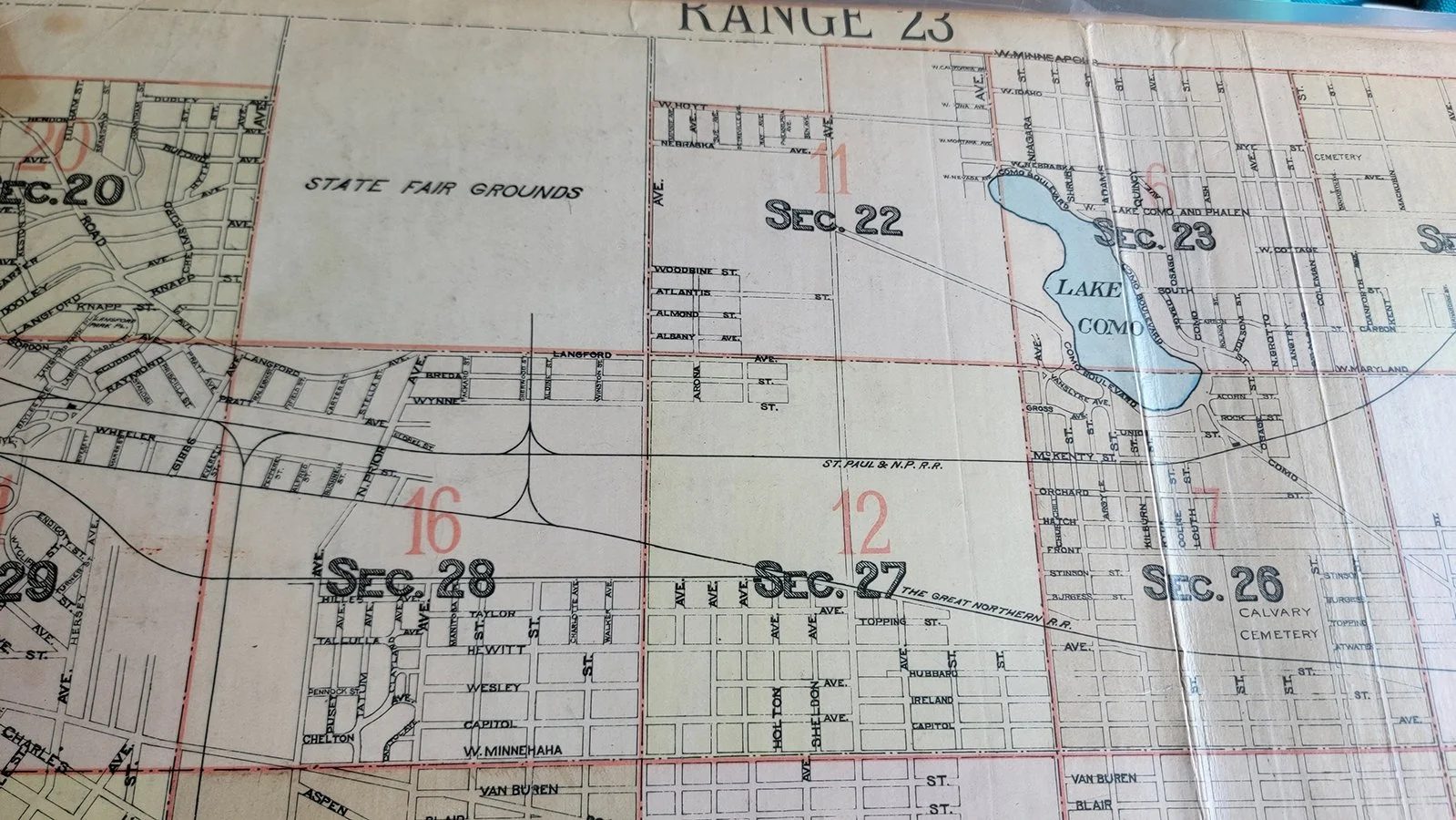

A zoning map, as imagined by ChatGPT. If only they were this colorful in real life!

Over the course of the 20th century, we've gradually stripped away the concept of property rights. In 1900, if you owned land, you could generally build whatever you wanted on it. Today the government determines the size, shape and design of buildings, as well as what activities are allowed inside them. This level of regulation is so widespread that the few exceptions — most famously Houston's lack of land-use zoning — are noteworthy and much discussed.

We've had a hundred years to get used to this, so we're not shocked by it anymore, but we should be. Most American cities today employ near-Soviet levels of central planning to micromanage the use of property. Unsurprisingly, we have crippling shortages of shelter and high rents.

Kevin Erdman put this very poignantly:

One way I would put a lot of the high costs that have crept into American housing is that zoning and land use regulations basically make the cost of many potential projects infinity, because they are simply prohibited. So, high costs end up being a negotiating tool for the developers. “What hoops can we jump through to get the cost of this project from infinity to $2 million?” Maybe in an unburdened market, it would only cost $1 million to build that project. But, $2 million is better than infinity. And, if a city has obstructed enough other housing, maybe $2 million can still bring in enough rent to justify the cost.

The story of how we got here is long and complicated, and many have told it, so I won't attempt to recap it today. The good news is that the tide is finally turning, largely thanks to three successive movements for change.

First, the New Urbanists helped us all realize that our beloved historic districts in American cities and small towns were not obsolete but rather illegal. They explained that the shape of our buildings and neighborhoods is no longer the product of a designer's creativity, but largely the mandatory output of a regulatory formula set by city legislation.

Second, Strong Towns and other media organizations built on the knowledge of the New Urbanists and raised the salience of dysfunctional local government to a much wider audience of concerned citizens. Twenty years ago, these topics were the niche interest of architects and planners; today, there's a much wider pool of nonprofessional interest and activism.

Finally, the YIMBY movement emerged with an effective strategy to organize concerned citizens and effectively pass legislative reform.

The crucial insight of the YIMBY movement is that policy change hinges on a fundamental asymmetry: The negatives of new development fall overwhelmingly on the immediate neighbors, while the benefits are diffused across the entire region. Similarly, if only one jurisdiction in a region liberalizes, the entire region's pent-up demand will concentrate on that single outlet. Broad reform is therefore difficult at the local level.

However, the YIMBY movement has shown us that this collective action problem can be addressed at the state level, where the diffuse benefits clearly outweigh the costs. So a key YIMBY strategy has been to use state preemption to remove barriers to housing across an entire state all at once. This has led to broad, substantial reform, and the movement is gaining momentum as it accumulates wins.

So, what changes are coming in the future, and what impacts might they have?

Single-Family-Only Zoning Will Be Relaxed

One of the first targets for reformers is single-family-only zoning. In most places, this is the primary impediment to building additional housing units, as local laws restrict the majority of land to individual, detached houses on large lots.

Reformers have been broadly successful at pushing for a more relaxed definition of residential zones that would allow a mix of small residential buildings to coexist. As these reforms accumulate, I expect we'll see today's strict single-family-only zones evolve to allow many compatible housing types by right, including backyard cottages (aka ADUs), accessory apartments (rent out a room), and homes with two to four units.

Another promising target is the elimination or reduction of minimum lot sizes. Lot size rules make it prohibitively difficult to add new housing in existing neighborhoods; where these rules have been relaxed, the housing supply has grown.

These rule changes are modest, but because the vast majority of American land is restricted to single-family-only development, even very modest incremental relaxation of restrictions in these zones will unlock more new housing than we could realistically accomplish via alternatives. Applied regionally, these reforms would create space for millions of new housing units lightly sprinkled across all our existing neighborhoods, so no single neighborhood would be forced to endure radical change.

Parking Will Be Deregulated

Another reform that's gaining broad momentum is the removal of parking requirements. Parking requirements seem to make intuitive sense —nobody likes driving across town only to find they can't park anywhere near their intended destination — but in reality, central planning of parking lots has resulted in comical waste across most of our cities. Strong Towns features “Black Friday Parking” every year on Twitter/X to display this waste: Even on the consensus busiest day of the year, America is full of empty parking lots.

There's a simple solution to this problem: deregulate parking. Who knows better than the business owner how much parking they need to operate? Who knows better than the homeowner how many cars they need to park? If we let individuals make their own decisions, we unlock lots of small incremental changes — a new corner store here, a new backyard cottage there — that can add up to a huge improvement in building supply.

There's also a proven solution to address the constant fear of neighborhoods: on-street parking supply. First, we need to understand that on-street parking is a city-owned public amenity. The city needs to take action to maintain that amenity, just like it maintains parks and libraries.

In areas of high parking demand, cities can create Parking Benefit Districts. In these districts, on-street parking is priced such that commercial streets always have 1-2 free spaces for convenient access. The revenue is then reinvested into the surrounding neighborhood — spent on improving sidewalks, landscaping and public safety.

In areas with low demand — such as neighborhood streets that only occasionally experience overflow from nearby attractions — parking can be given a time limit or restricted to residents with neighborhood parking tags.

If we combine these two approaches — free property owners to use their land and then protect the public amenity of street parking by actively managing it — we can unlock millions of opportunities for starter houses, backyard cottages, art galleries, corner stores and more. We'll make our neighborhoods nicer, lower the cost of housing and support local businesses.

Just Over the Horizon

While not yet widespread, two other incremental development reforms have been gaining recent attention:

Preapproved building plans: South Bend, Indiana has pioneered preapproved building plans. Rather than requiring a lot owner to hire an architect, pay for a custom design, and then play a game of guess-and-check with the city to find out if it will be allowed, property owners can pick from a catalog of preapproved building designs and get a permit immediately. This saves owners a lot of time and energy, while also guaranteeing that they'll build nice buildings that fit well with the surrounding neighborhood. More cities are considering this as an option to streamline the construction of things they know they want.

“Shot Clocks”: The worst problem with development regulation is that it's often nondeterministic and can be held up indefinitely. It can take many years to get approvals, if they can be obtained at all. By contrast, Minnesota has a broad automatic approval statute: Many state authorities have 60 days to make a decision or else the development is automatically approved. This forces cities to actually make decisions about projects, not just leave them in limbo forever. Texas recently followed Minnesota's lead with an even shorter 15-day shot clock for residential projects. More cities and states are considering adopting shot clocks to ensure reasonable development review times.

Distant, but Possible

These changes haven't emerged in the wild yet. However, they are rising in the discourse in the same way that changes like relaxing single-family-only zoning were 10-20 years ago. While I think the probability of these changes occurring is low, they build on the higher-probability reforms above in a logical way, so it's possible we might see movement in these directions if the reforms above are widespread and successful.

Lower bar for owner-occupants: Cities have good reasons to be skeptical of large-scale developers building huge projects that fundamentally change the neighborhood. But there's a lot less risk to individual owners doing small-scale projects for their own home or small business. By definition, they have a lot of skin in the game, and they have to face the neighbors! Cities could embrace this and offer simplified rules and streamlined permitting for owner-occupants.

Next increment by right: One of Strong Towns’ priority campaigns is to allow the next increment of development by right. In other words, if you currently live in a single-family home, you should be allowed to make a second unit in your home, whether that's by adding a backyard cottage, retrofitting an apartment or even remodeling into a duplex. If you own a corner store, you should be allowed to build a second floor for an office or apartment space. These small incremental changes are part of the magic of how cities have always evolved — we've unnaturally shut this process down, and we need to bring it back.

Adaptive Code: An idea I first wrote about and championed back in 2010, “Adaptive Code” is the idea of reforming our whole system around the idea of “next increment by right.” Instead of drawing colors on the map to determine what's allowed, we'd replace zoning with a formula that looks at what's built on neighboring lots and allows a slight increase. We can imagine a very simple version of this: If both neighboring buildings are one story tall, then a two-story building is allowed. Bits of this model exist in the wild — for example, Denver's setback rules roughly say that a building must be built as close to the street as its neighbors are.

Repealing Euclid: The most radical change would be to reconsider whether the city has the right to dictate what landowners can do with their property at all. This Supreme Court precedent is a strange outlier compared to the rest of property law, and it's possible to imagine a well-crafted legal appeal could rise to the level of the Supreme Court and overturn it. This seems unlikely today, if only because it would be such a radical change from the status quo. However, if land use reform gains momentum for another decade or two, we could imagine repealing Euclid as the climactic moment in a generational effort to restore property rights.

Conclusion

There's tremendous widespread momentum for relaxing single-family-only zoning and removing parking minimums. Thus, there's a very high probability that these reforms will be adopted in most of the country in the next decade. Other incremental reforms are highly likely to pass in specific locations as cities experiment to try and solve their development problems.

When we combine these land use reforms with the transportation evolution that's already underway, I expect we will see a major shift in how our cities grow.

Since the 1950s, most growth has been via horizontal expansion. I believe that, in the next 70 years, we're likely to experience an inversion where most growth is incremental infill.

Instead of the default new house being a DR Horton subdivision built on the edge of town, the default new house will be a townhome blended into an existing neighborhood. Instead of the default new apartment being a massive 5-over-1 at the edge of a historically lower-income neighborhood or built on a new suburban arterial, the default new apartment will be a fourplex built a block or two from a neighborhood main street. Instead of the default new commercial space being an office park or strip mall, the default new commercial space will be a second floor added to an existing retail building or a new shop built over formerly underused parking spaces.

All of this means that there will be an enormous economic opportunity for the neighborhood incremental developer over the megaproject builder.

To learn more about enabling incremental housing, removing parking mandates and strengthening neighborhoods, check out these Local-Motive sessions:

September 12: The Parking Revolution Is Here. Is Your Community Ready To Sign On?

September 26: Investing in Housing Development That Strengthens Neighborhoods Without Pushing People Out.

October 10: Creating Neighborhoods for People of All Ages.

Attend live or get access to past session recordings on the Strong Towns Academy.

Andrew Burleson has served as Chairman of the Board for Strong Towns since 2014. Andrew’s professional work has spanned several fields, from newspaper publishing and urban planning to real estate and financial technology. Before Strong Towns, Andrew founded the Houston chapter of the Congress for the New Urbanism in 2009, and he met Chuck Marohn through CNU. Andrew has been a key advocate for Strong Towns’ evolution from an engineering-centric blog to a broader, movement-building organization. Andrew lives in Denver, Colorado, with his wife and four children.