America's Suburban Experiment

For thousands of years, humans built settlements scaled to people who walked. Even as inter-city transportation technology changed from domestic animals to trains and cities began to develop streetcar networks internally, the vast majority of daily trips were still made by foot.

This, of course, changed with the advent of the automobile, a technology that became ubiquitous in America following World War II. Over the past two generations, we have reshaped an entire continent to accommodate this new technology, from interstates to connect our cities to the streets within them. We developed new building types, new ways of arranging things on the landscape and new standards for building and financing this new way of building, all from scratch, all within a very short period of time.

If the typical American is asked to explain this transition, they would likely describe it as a narrative of progress. We used to be a people who walked everywhere and so we built cities around people who walked. We are now a people that drives everywhere and so it is only natural that we have built a society around people who drive. At some point in the future we will have jet cars and ultimately we’ll just teleport wherever we go and our cities will look completely different than they do now.

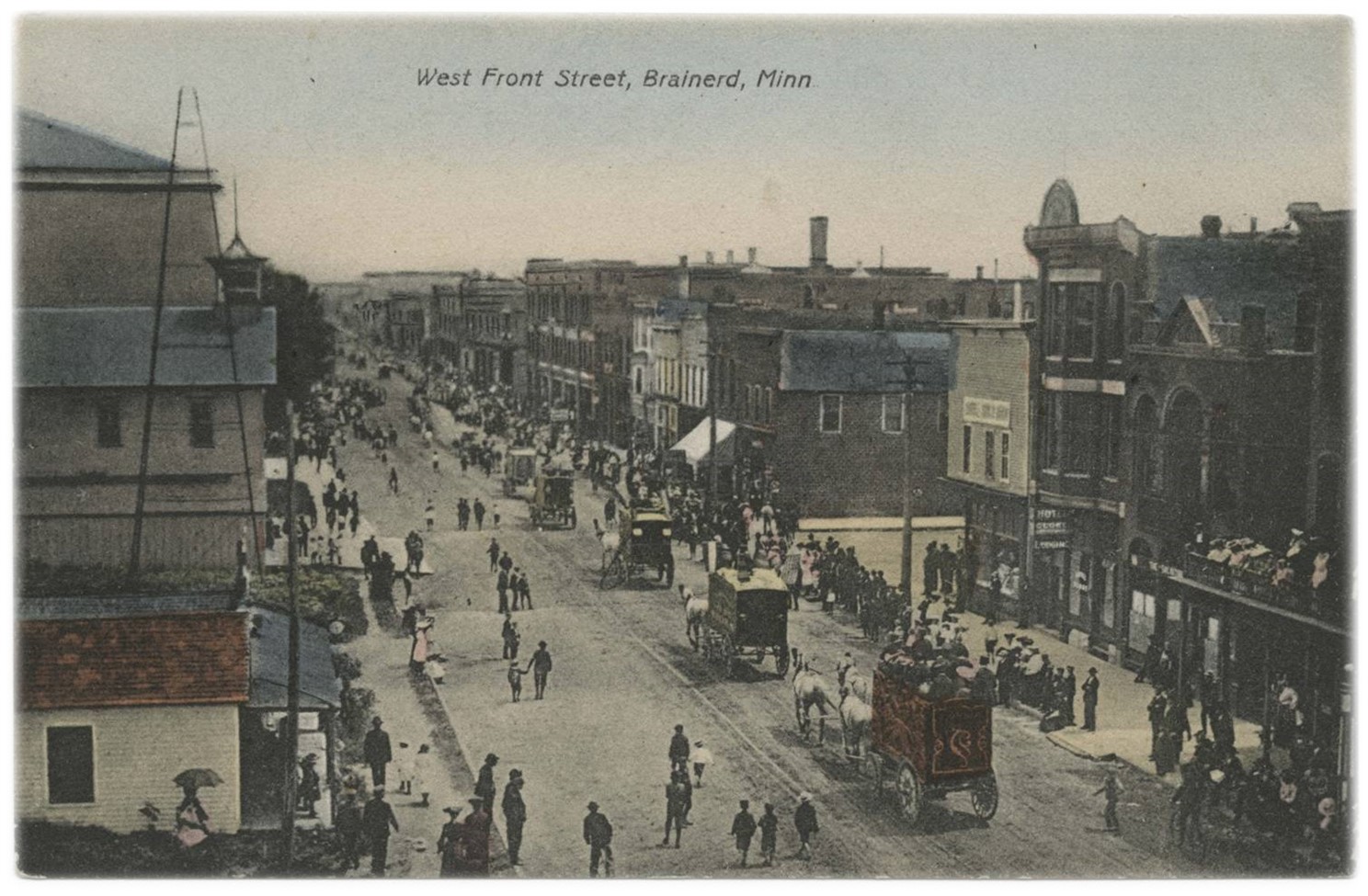

Chaotic but smart in America's Midwest. This is Brainerd, MN, in 1904. It was developed on the same, basic, human-scaled model as thousands of years of cities that preceded it.

This is a very comforting way to view the changes of the past sixty years. It places us firmly on the path of improvement, of ever-expanding prosperity and opportunity. In a word: progress. There is another way to look at this, however, that isn’t so affirming.

These pre-automobile cities, big and small, built on different continents and at different latitudes by different cultures around the world, share an eerie similarity of design. When we look back at the way prior human civilizations built their places, when we study the way they assembled their streets, designed and placed their buildings and phased their infrastructure, we can start to appreciate the wisdom embedded in this approach, understanding that was developed over thousands of years of trial and error experimentation.

Societies tried things. What worked they copied and expanded on. What didn’t work they stopped doing or their society failed. Over the slow grind of time, during times of growth and times of decline, times of prosperity and times of want, humans refined this approach. By trial and error, our ancestors optimized the craft of city-building to the social, cultural and financial realities of complex societies. The results were far from perfect, but there is no question the cities they built had tremendous resiliency. They even benefitted from moderate levels of stress, a phenomenon Nassim Taleb calls antifragile.

Orderly but dumb. We can create growth, but we lose the resiliency of the slower, more incremental development approach.

Concurrent with the advent of the automobile came many other technological and social changes that allowed modern humans to dream big. Cheap fossil fuels. Advanced communication technology. Centralization of decision-making. Proactive management of the national economy. We attacked the problems of the traditional city with the fervor of a great nation empowered to think differently.

We developed different building types. Different building styles. We came up with different ways of arranging things on the landscape and different ways of connecting these places. We developed an entirely new system of regulation to rapidly replicate this new pattern along with the financing mechanisms and economic incentives to make it happen.

This all seems normal to us today – for most of us, it is all we have ever known – but it is critical to understand that, in the course of human history, the American development pattern is one of the greatest social, cultural and financial experiments ever attempted. The knowledge we apply daily in this experiment wasn’t developed by trial and error over the slow grind of centuries. It was advanced in academia and within government meeting rooms, initially based largely on the theories of European intellectuals.

We didn’t try it out for a couple of generations in one part of the country to see how it would work. We just did it. Everywhere. All at once.

“We didn’t try the suburban experiment out for a couple of generations in one part of the country to see how it would work.

We just did it. Everywhere. All at once.”

Our auto-oriented development experiment, now in its third generation, has allowed the United States to experience decades of robust growth. Despite this success, our cities and states – big and small, led by liberals and conservatives alike – are now struggling to find the money to do basic functions. Simple things like maintain sidewalks, fix potholes and keep public safety departments adequately staffed. How can this be?

The answer is that, in this new and enticing model, we’ve sacrificed resiliency for growth. In the pursuit of jobs and economic development, American cities have spread themselves out beyond their abilities to financially sustain themselves. All those roads, all that sidewalk, all those pipes....they are really, really expensive. We're starting to understand that building it all was the easy part. Maintaining it generation after generation is hard.

And now, as budgets everywhere are frayed, our leadership obsessively seeks - in true Ponzi scheme fashion - more and more growth using this same, experimental model.

America’s cities don’t need more growth. What they desperately need is a different development pattern, one that restores the resiliency and financial productivity of the pre-automobile approach to a modern America.

America’s cultural belief is that growing cities experience not only opportunity and prosperity today, but also success far into the future. There is a built-in assumption that new growth pays for itself today and generates enough wealth to sustain itself generation after generation This is a flawed assumption.