The nature of productivity

If we are going to make transportation investments as a way to create jobs and economic development, we should be doing so in places with a high return. Spending scarce resources to make STROADs modestly safer is not helping, especially if it induces more people to drive. What our cities need right now is to invest in productive patterns of development.

We're making final preparations here for our big trip to Pennsylvania next week. Justin Burslie and I will be flying to Philadelphia this Sunday and then, starting early Monday morning, will be making more than a dozen stops as we make our way from town to town to share the Strong Towns message. If you live in or near Pennsylvania or have friends, relatives or acquaintances that do, check out the schedule and try and make one of the Chats. We'd love to meet you.

Yesterday we examined a dangerous intersection along a STROAD, one where the frequency and severity of accidents prompted a severely cash-strapped DOT to spend good money making modest safety improvements. This, despite the fact that the dangerous intersection is less than 1,000 feet from an expensive, fully signalized intersection maintained by the DOT, with the full complement of expensive frontage roads feeding back into it.

While closing the dangerous intersection would improve traffic flow, improve safety and cost less than the extensive reconstruction recently done, it remains open. For all involved, the seconds saved in accessing the adjacent big box retail establishments outweigh in value any other considerations. This must be one valuable location.

Or perhaps not.

The most valuable property in this section of STROAD is the Mills Fleet Farm site. The four parcels includes the Fleet Farm big box store, a Mills Motors auto dealership, a Mills gas station and related parking and storage. Of the four corners accessed off of the dangerous intersection, this is by far the most valuable (and the one with the highest traffic demand). The others are a collection of half-vacant strip malls, underutilized former big boxes, pole buildings with fake facades and other structures of much less value.

The Fleet Farm site is 22.8 acres. It has a total value of $14.4 million. The productivity of this site, in terms of value per acre, is $630,000.

Most cities would bend over backwards in order to have that kind of tax base. This is the kind of growth we get -- and celebrate -- when we make a nine figure investment in a major highway improvement. The Mills corporation pays a ton of taxes to the City of Baxter, Crow Wing County and the State of Minnesota. It is not difficult to imagine a world where the state, with all good intentions, would drop half a million dollars improving a pesky intersection that has proven frustratingly dangerous.

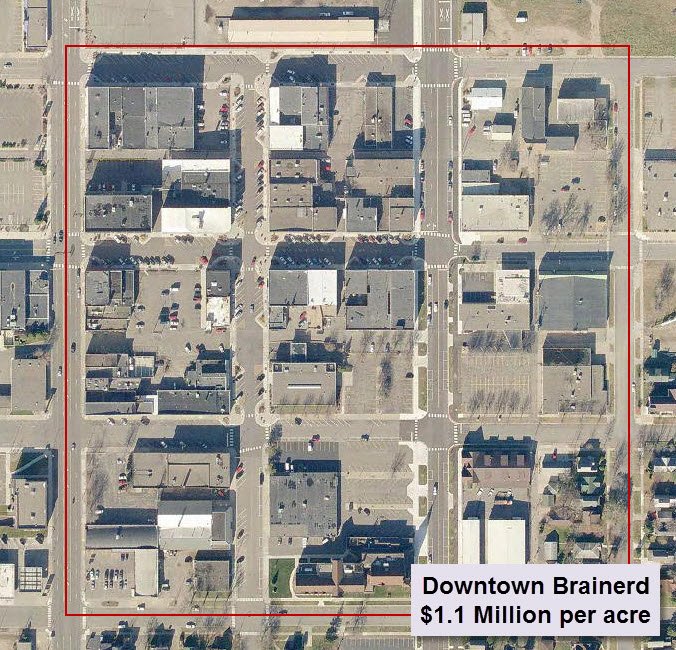

In order to provide an apples to apples analysis, I went to the adjoining city of Brainerd to make a comparison of the Mills site -- the most productive site on this STROAD -- to the productivity found in the traditional development pattern. The nine blocks of downtown Brainerd shown below create a site of slightly less size -- 17.4 acres -- but far greater value. The total value of these nine blocks is $18.9 million, a per acre productivity of $1.08 million, a 72% premium over the Mills STROAD site.

There is an important thing to note about this part of downtown Brainerd. While it is financially the most productive part of the downtown, that is not saying much. There is a small area where the streetscape has been given a freshening up, but most of the development is of pretty low quality. I've brought some of my planning friends from out of town there to survey the damage and they are always shocked at how bad it is. The neglect and atrophy is depressing, even more so when you know what it used to look like.

You can also see from the photo just how much of the space has been given over to automobile storage. In a race to the bottom, Brainerd has destroyed its tax base in an effort to achieve the parking ratios found along the 371 STROAD. Yet that historic value endures.

There are some important takeaways from these observations.

There are some important takeaways from these observations.

First, and most obvious, is the productivity machine that is the traditional development pattern. There are good reasons that thousands of years of trial and error produced this style of development. Even after two generations of neglect and disinvestment, it remains financially superior -- by a large margin no less -- to the most productive similarly sized STROAD investment in the area.

Second, the traditional development pattern is antifragile in so many ways while the STROAD development is anything but. In the downtown there are 132 different properties, many with multiple tenants. On the STROAD we have one corporate owner. With those 132 different properties, we have an entire ecosystem (albeit a starved one) of jobs, investments and micro opportunity. On the STROAD we have no such diversity; it is all in the hands of one business and their model. Downtown we have resilient building types where one storefront can be an office or retail or service or even residential, depending on the market demands and conditions. When the big box on the STROAD closes, there are few happy things that come next.

Third, since the beginning of the Suburban Experiment, we have had infrastructure throughout the downtown. No new investments have been required to obtain this premium return. To get the far inferior returns from the STROAD, we have spent over a hundred million dollars on highways and frontage roads along with tens of millions on sewer and water systems, all long term obligations that local taxpayers must now sustain on a meager, diffused tax base.

Fourth, the original impetus for this conversation was the way we willingly sacrifice safety for low-return economic development along the STROAD. Well, the traditional development pattern has no such safety concerns (although in this instance, the city of Brainerd has insisted on a high speed, dangerous design through their traditional neighborhoods). We may have fender benders, but your grandmother is not going to get smashed by a semi trying to time a highway gap fleeing from the road rage driver on her tail.

And finally, when we come to grips with the reality that the problem of our cities is not lack of growth but lack of productivity, we will ask ourselves: how do we make our places more productive? Look at the STROAD site. Unless there is an heroic effort by a well financed and determined developer, there is no way the value of that property ever doubles (in real terms). There is no way the parking is converted to structures, a second story is added and other improvements are put in place to improve the value and return on that site. And even if this happened, it doesn't fit with anything around it. It would become an isolated point of productivity in a ring of decline. Today's low return condition is the financial high water mark.

The traditional development pattern of the downtown not only starts the productivity race 72% ahead of the STROAD, it has lots of opportunity to grow. All of the parking can easily be converted to more productive uses. When that low hanging fruit is consumed, all of the buildings can be improved. The second and third floors can be recaptured, renovated and remodeled. This doesn't require one sugar daddy but can be accomplished through the organic functioning of many different players. And when this happens, it won't suck the life out of the surrounding properties. To the contrary, this can only happen successfully in conjunction with the surrounding neighborhoods. Even though the current downtown is far more financially productive than the STROAD, the current atrophy and decline should be the low point. With a little different focus, it is easy to envision the value of these nine downtown blocks doubling, tripling or more.

Now go back to the cash-strapped DOT; if half a million dollars is going to be spent on transportation improvements, and if economic development considerations are going to trump safety, the numbers would suggest that retrofitting the STROAD through the downtown to be more neighborhood compatible is the investment with the highest return.

That is what a state looking to build strong towns would do.

If you are interested in getting into some of the numbers behind this post, head on over to the Strong Towns Network where I've shared the data and methodology. If you want more of this type of analysis, check back here Monday, Wednesday and Friday each week or, for a quick primer, you can check out my book, Thoughts on Building Strong Towns (Volume 1).