Car Dependent By Design

I am writing a series of blog posts on my website about zoning, starting with my previous blog post on the different types of zoning systems. In this post, I will be talking about how single-use Euclidean zoning is distorting market demand, and how many places are automobile dependent by design. If you do not know me by now, I am 'traditional urbanist' - I advocate for pleasant fine-grained, human-scaled, organic urbanism. Anything that goes against this is, in my mind, a very bad idea. I will also present one possible alternative approach to Euclidean zoning that our towns and cities can easily transition over to.

What We Asked For

I will be referencing the zoning system in Conway, Arkansas as an example, not because I am picking on you Conway, but because I live here and it is much easier to reference a place where I have lived.

You could argue that we live in a free market country. That all of our decisions are based on what people want - that Conway is sprawled because the people want the city to be sprawled, and that Conway is automobile dependent because people want to drive.

That is a bunch of baloney.

Conway, like most cities around the country, is that way by design. The development pattern we planned for is ultimately the development pattern we got. Everyone else is just responding rationally by building what you wanted them to build.

Conway, Arkansas uses single-use Euclidean zoning for virtually all by a small patch of blocks downtown. Each zone is assigned a use - as well as some 'engineering standards' (setback, spacing, height, yard, and parking requirements.) For reference, you can download Conway's zoning code from their Planning and Development website.

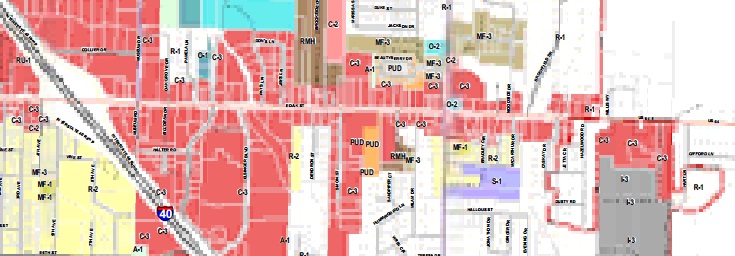

Here is the zoning map for Conway - it is very colorful;

(Click here for a larger version.)

One thing you will notice is the scale. There is a whole lot of white with a bit of blue, gray, and red - mostly clumped together. Let's zoom up on a specific neighborhood;

I can see a lot of white R-1 residential (which means single family detached residential properties) grouped together along cul-de-sacs and disconnected streets that connect to the odd blue C-2 (suburban commercial) properties and red C-3 properties ("to encourage the development of recognizable, attractive groupings of facilities to serve persons traveling by automobile" - quoted from the planning ordinance, page 53) along two commercial corridors (one at the bottom and one at the top.)

The scale of the diagrams - the distance between the different uses - are at an automobile scale. A common reason people drive is that distances are too far to walk - the other is that it is too dangerous. We can solve one problem by building sidewalks, but since our plan spaces out land uses, only very few people will ever live within walking distance of a destination - so rarely would anyone in this neighborhood attempt to walk.

The shops within walking distance happen to be zoned C-3, of course, and have been built in a form that targets motorists. If everyone else drives there - why do you want to be the only one that walks?

If we look at East Oak Street;

We would be forgiven for thinking that auto-oriented retail was the only thing that can prosper in our city. But, why?

Perhaps it is because someone zoned it C-3;

..."to encourage the development of recognizable, attractive groupings of facilities to serve persons traveling by automobile." We got what we asked for.

What we are zoning for is what we are asking to be built there (or let it sit vacant until there is demand to build that - as we see with all of the empty industrial properties around the city.) There is nothing about our cities that is inevitable or unchangeable. Everything is the way it is because of we made choices at some point for it to be that way.

If we want our towns and cities to be less automobile-oriented then we cannot keep doing more of the same - or we will get more of the same. If we continue to zone for automobile-oriented uses at automobile scales than we are going to continue to attract automobile-oriented development. It is that simple. Developers and investors are only responding rationally by building what you are asking them to build.

Technically, any property owner can petition their city to get their property rezone. Rezoning can be a slow process, and whether your rezoning is granted depends of the traffic engineer's and planning commission's long range plan. Without adequate convincing, most council members would prefer to vote erring on the conservative side of keeping the existing zone. The rezoning process favors those with political pull and the time and resources to get it done - compare the chances of an outlet mall or subdivision developer asking to rezone a greenfield, to the neighbor that wants to open a small business on the corner of his street - which is more likely to be approved? This is a huge impediment to incremental, organic growth - the type of growth that cannot be predicted or planned for by a city planner behind a desk looking at a map.

An Alternative Approach

The typical implementation of single-use Euclidean zoning does have its downfalls, and I never like to criticize or complain without offering an alternative. While one alternative may be to abandon zoning altogether ("But, Andrew - how can I prevent a factory from opening up next door?" "How will we prevent uncontrolled sprawl?") - which I will discuss in a future blog post, or adopt a form-based code, I am going to propose an alternative use-based zoning scheme that tries to keep the advantages (but not the disadvantages) of Euclidean zoning that we can easily transition over to.

What would this zoning scheme look like?

First, we must gather the requirements of our new zoning scheme. For our first set of requirements, we will take the arguments for Euclidean zoning;

- We must be able to restrict undesirable development next door (a factory next to a house, for example) and maintain property values by guaranteeing that.

- We must be able to limit uncontrollable sprawl and horizontal expansion.

- Our existing zones need to easily translate over into our new zoning scheme.

Since we wish to design something better than Euclidean zoning, our requirements are also to mitigate the negative effects of Euclidean zoning;

- Euclidean zoning, by setting an exclusive land use, prevents incremental growth and investment that intensifies a property or its use to the next level.

- Euclidean zoning may not always respond to market demand for different use types - for example, industrial or commercial land that sits vacant for decades simply because of its zone or location.

- Euclidean zoning micromanages the specific use of each property - which may not be the most optimal based on its location and market demand.

While there are multiple directions in which we can head, for example - not regulate land use and adapt a form-based code instead, in this blog post I will propose an alternative way to regulate land use - maximum-use zoning. In traditional Euclidean zoning, we assign an exclusive use to each zone, while in maximum-use zoning we assign a 'maximum use'.

To describe how maximum-use zoning works I will use a very simple (but dumb) example - one where each zone corresponds to a simple metric like density or height;

When we zone a property, we zone the highest that we are willing to tolerate there. For example, if we zone a property "Rural" - it cannot be used for anything but farmland. If we zone a property "Exurban" - we would allow both farmland and low-rise. If we zone a property "Suburban" - we would allow farmland, low-rise, and medium-rise development. We are not forcing medium-rise development, but instead we allow incremental growth and intensification up to the desired maximum density.

However, this overly simplified system fails at our first requirement above - to be able to restrict undesirable development next door. We are not preventing a warehouse or sports stadium from opening up in a residential neighborhood - fully acceptable low-rise uses.

A better system would be one where uses and zones are sorted by their 'annoyance level' - the higher the zone, the higher the 'annoyance level'. For example, a store next door may 'annoy' a homeowner, but a business owner may not mind a house next door. So we will say that businesses have a higher 'annoyance level' than houses. By breaking down uses by how 'annoying' they are, we can come up with a simple table of zones and uses;

In the residential zone we allow incremental development up to detached houses, and folks that want to live in a purely residential area would find a house in a residential zone. Neighborhood zones would be your typical neighborhoods - allowing detached houses, but also allowing townhomes, corner stores, churches, schools, and mixtures thereof (such as corner stores where the shop owner lives out the back) - uses you would typically find in pre-war neighborhoods. In a town zone you would find uses that are typical of a Main Street or a commercial corridor - we allow both medium-rise urban development as well as auto-oriented development, allowing the market to determine in which direction there is demand for. Business zones are the urban cores of medium and large cities, while industrial zones - the most annoying of all - allow absolutely anything to be built there.

The advantage of this system is that it allows for incremental growth - upzoning an area would never exclude or grandfather in previous uses, but rather allow incremental growth toward the new acceptable uses if there is demand for it. Homeowners purchasing homes within neighborhood zones will be assured that they will never live next to a outlet mall, and this could increase the desirability of neighorhoods as well as increase home values, while to others, it may be desirable living within a town zone close to their place of employment. A retail owner may be concerned that the value of their business would be destroyed if a factory opened next door, and so they locate their business within a town or business zone, while other retailers may find a niche and thrive in industrial zones - targeting hungry workers and commuters.

I have just presented one, not necessarily the best, alternative to single-use Euclidean zoning that a typical town could easily transition over to.

Conclusion

Single-use zoning can distort the supply and demand of property and is far from a free market system. If we zone automobile-oriented uses at automobile scales do not be surprised if the result is an automobile dependent environment. Nothing about this outcome is inevitable though - it all depends on the choices we make while planning our city.

The question at the root of the topic that we need to ask is - why does your city zone?

Over the past half a century or so since your zoning code was implemented - has zoning worked? Has zoning achieved its goals? Has it done more good than harm? What was your town or city like before you implemented zoning? (Was the result so bad back then that you needed zoning?) Is there an alternative approach you could take that could achieve your goals but mitigate the negative effects of your current zoning system?

I have proposed one way you could transition over to a maximum-use zoning system, but there are many alternatives and I encourage anyone out there interested in planning and zoning to innovate and come up with their own alternatives. We need a better approach than the single-use Euclidean zoning system we use today that micromanages uses, limits growth, and distorts demand.

This post is my second in a series on zoning, starting with my previous blog post on the different types of zoning systems. In the future I am going to deconstruct zoning more, and discuss topics such as how to plan without zoning, rational building height limits, and in particular, discuss what is wrong with Houston (the example often given of a large city without zoning.)