Still Pursuing Classic Approaches. Still Going Nowhere.

My home state of Minnesota has a new governor this year, and there was some realistic hope during the campaign that his election would mean a shift in transportation policy. I’m proud of many of the thoughtful approaches of which my home state has been an early adopter—Minneapolis’s embrace of incremental development by right as a citywide policy being the most recent—but Minnesota has been a laggard in transportation, sticking to an antiquated approach of road building and commuter-focused transit with a sprinkling of (largely recreational) bike infrastructure sprinkled in. Would that now change?

In short: no. The governor appointed an old guard politician to run the state Department of Transportation, embraced a gas tax increase early on, and is trying to sell it to rural districts (read: Republicans with slim but seemingly united control of the Senate) by touting more road building. In many ways this feels like we’re going backwards.

I had a busy weekend as a dance dad and find myself in my Sunday night writing routine on the brink of exhaustion, so I’m instead going to share a post I wrote back in 2015, the last time a massive transportation bill was on the brink of being adopted here in Minnesota. It’s really astounding how it is basically the same players making the same arguments with the same flawed assumptions. Having spent the last four years traveling North America talking Strong Towns in cities big and small, I know this is going to sound sadly familiar to most of you.

I was talking about this with someone this past weekend, and he argued that we need to maintain our roads so people can get to work. I told him that I thought our transportation investments were one of the largest drivers of income inequality ever—if not the largest—and that every dollar we spend building new and expanding existing transportation infrastructure is a dollar spent undermining the financial health of our cities, towns, and neighborhoods, not to mention our families and small businesses. Under the prevailing approach to infrastructure spending, the more we build, the poorer we become. I’m for reform, but if you give me only two choices—(a) double down on this destructive status quo or (b) de-fund the system and force it to devolve—I’d pick the latter every single time.

Baxter, MN, is the "classic case" of what we get with our current transportation funding approach.

The Classic Case

Last Friday on Minnesota Public Radio, there was a roundtable discussion on transportation policy. Featured in the conversation was Margaret Donahue, Executive Director of the Transportation Alliance, the group spearheading the Move MN coalition calling for additional transportation funding. When discussing the economic benefits of modern transportation spending, Donahue cited three examples: the Green Line light rail transit project in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Highway 212 improvements and the following (38:40):

You look at [Highway] 371 through Baxter as a classic case. It used to be a sleepy little town and now there's just business after business after business.

Baxter just happens to be the city I grew up in and where I worked as an engineer for a number of years. I totally agree: it is a classic case of what our transportation investments get us. Where I disagree with Donahue, as well as the insiders and vested-interests that comprise the bulk of her coalition, is that this is a positive example.

Baxter is the typical American Ponzi scheme city. In fact, it is one of the principle inspirations for the body of thought that is the foundation of the Strong Towns movement. From my office window, I watched the 371 bypass of Brainerd be built in the late 1990's. On my desk were a number of projects that today comprise the "business after business..." that constitute this corridor. It will look sadly familiar to where you live, I'm certain.

Business after business after business....

If you support the Move MN proposal for additional transportation spending (or similar proposals being floated around the country), here's what success looks like: Super Walmart. JC Penny's. Home Depot. Costco. Kohl's. Mills Fleet Farm. Cub Foods. Gander Mountain. Super 1. Target. Best Buy. Office Max. Mendards. Two Holiday gas stations. Two Super America gas stations. Arby's. Culver's. Taco Bell. The Olive Garden. Buffalo Wild Wings. Kentucky Fried Chicken. Pizza Ranch. Bonanza Family Restaurant. Subway. Starbucks. Applebees. Cherry Berry. NAPA Auto Parts. NTB Service Station. Super 8. AmericInn. Comfort Suites. Holiday Inn. Multiple car dealerships, a number of banks and a collection of miscellaneous bets, big and small, tied to the success of these national and regional chains.

"Success" in our current transportation funding system means more of this, Baxter's Highway 371 strip.

Yes, Baxter used to be a sleepy little town. The construction of the Brainerd bypass through Baxter made millionaires out of a handful of lucky bumpkins whose ancestors homesteaded the fortunate pieces of woods and swamp a century ago. This paved the way for the predictable collection of national chains that our transportation investments are designed to subsidize. And while the former owner of the now-failed local grocery store can become the night manager at Walmart (true story), the former owner of the now-failed downtown shoe store can sell shoes at Kohls and the former owner of the now-failed downtown pizza place can run the lunch crew at Applebees, only a handful of people are really benefiting from this arrangement.

“It’s a system set up to make the wealthy wealthier.”

This collection of businesses is not making the people of Baxter wealthy. Quite the opposite: it is sucking wealth out of the community, limiting jobs and opportunity in the process. As we pointed out a year ago in our piece on Dunkin Donuts, the wealth needed to compete in this government-led economy is out of reach for almost all Americans. It's a system set up to make the wealthy wealthier. In return, the unwashed masses get cheap imported stuff and fast food.

The city of Baxter does get more than that. The local government got a generation of robust growth, a period of time where cash was plentiful, stuff was shiny and new and everyone involved (including me, to a degree) looked like a genius as a result. That time has passed and Baxter now finds itself in the second phase of the suburban Ponzi scheme: the hanging-on phase. Taxes are going up, debt is going up and the old way of doing projects is getting harder and harder to pull off. It's becoming really difficult to maintain all this stuff without the new growth providing easy cash; there just isn't enough tax base and what's there just isn't financially productive enough.

Of course, the next phase is decline, when deferred maintenance and accumulated debt gives the city few alternatives to respond when these chains start to fail or move on to a shinier and better place. Detroit is future. Ferguson is future. Those places once thought they had it figured out as well, that massive transportation investments would bring them continual prosperity. They were responding to short-term incentives, just like we are here.

The sleepy little town

This is a map of value per acre for each property in Brainerd and Baxter. The higher the rise, the greater the financial productivity. Brainerd has not had the growth that Baxter has had, yet the tax base in its core neighborhoods is for more financially productive. The auto-oriented development pattern might create quick growth, but it doesn't create enduring wealth. Analysis by Urban-3.

The neighboring city of Brainerd is now the sleepy little town. This is where Highway 371 used to run and Brainerd -- like thousands of cities around the country -- once saw highway-oriented development as its salvation.

That hasn't worked out so well. Those places on the edge of town are now the ones in steep decline, with high long-term vacancy rates and rapidly falling property values. In contrast, the core neighborhoods of Brainerd and its downtown -- the areas built before the auto experiment -- are holding their value, despite disinvestment and decades of neglect from the city.

And despite the state dramatically tilting the economic playing field away from Brainerd's small business ecosystem and towards the national chain corridor of Baxter.

If this seems counter-intuitive to you, there is a reason for that. We've come to associate, as Ms. Donahue has suggested, transportation improvements with success. In that we've mistaken the shiny-and-new for the resilient-and-timeless. See our writings on the math of Taco John's and also The Foolproof City if you want some data behind that assertion. This is the story of America post-World War II, and it's why our cities are struggling to find the money to do simple things, despite all of America's growth and wealth. Our transportation investments destroy far more community wealth than they create.

Good politics. Bad policy.

So why would a transportation advocacy group be pushing for billions in new spending on transportation projects that have such low financial returns? Why would such a group want to make investments that dramatically weaken our core cities? Why would those deeply involved in transportation policy not be pushing for dramatic reform of this system before giving it the steroid of a major cash infusion?

There are two simple explanations. First, look at the members of the coalition. The Gold and Silver sponsors of the Transportation Alliance are primarily a collection of the nation's largest engineering firms, major companies that directly benefit from this government spending. The Move MN coalition is broader but is still dominated by contractors, labor unions and those that stand to profit from an expansion of the status quo.

The second explanation is that this is good politics. Despite the underlying reality, most Americans do associate shiny-and-new with success. Transportation projects provide an immediate feedback to our senses that we're conditioned to interpret as progress. An opaque tax on wholesale gasoline is the least noticeable way to continue to provide what I've called the modern equivalent of Rome's bread and circuses.

Questions for the unwashed masses

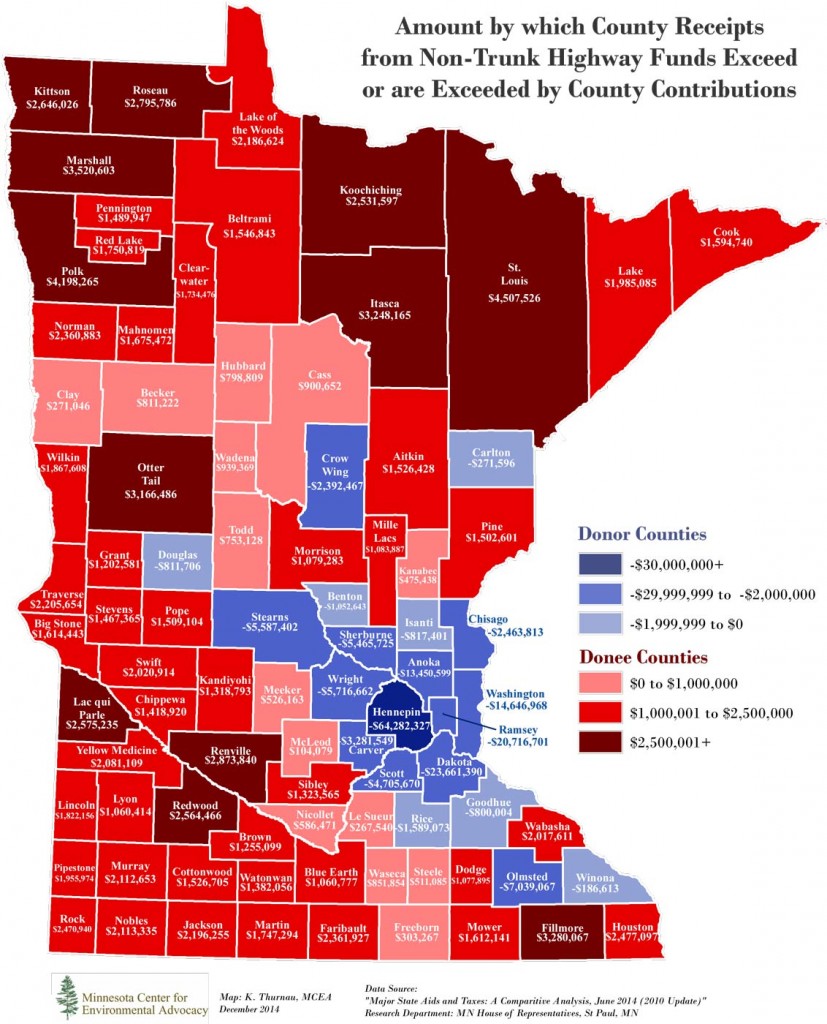

If you are passionate about major urban areas, why would you want to spend more money on a system designed to take the wealth of cities and direct it to pork-barrel projects in rural areas? Why wouldn't you just keep your money in the city and spend it on your own priorities?

If you are passionate about small businesses, why would you want to continue to subsidize large corporations and national chains and, in the process, create enormous financial barriers for small business success?

If you are a bike/walk advocate, why do you have any confidence that the DOT has even the slightest comprehension of your needs? Why would you agree to partake in the table scraps of a system that considers unwalkable places its greatest successes?

If you are passionate about transit, why would you not opt to fund great transit systems in your own places with your own money instead of sending all that money elsewhere for more highway strip development and then get suburban-commuter rail in exchange?

If you are passionate about the environment or climate change, why would you support an approach that is going to continue to expand an already bloated, auto-oriented system as a precondition to anything else?

If you are a fiscal conservative, how can you support a tax increase -- or even worse, more borrowing -- for a system that is so financially unproductive and dominated by special interests?

If you care about social justice, how can you be complicit in building more and more places that are designed to fail?

If you are a member of a trade union, do you not see how the franchisement of America has denuded your ranks to the lowest levels since the suburban experiment began? Are you for the worker or, as your critics would assert, do you simply advance your own narrow interests at the expense of society?

Conclusion

Perhaps the most revealing, albeit disturbing, part of the MPR interview came at the 33:34 minute mark when the conversation had turned to exactly how much money was needed. This has been a source of dispute because Mn/DOT has released many different numbers, each time getting further from reality and closer to the politically expedient. Here's what Ms. Donahue had to say on the matter:

We can study it to death. Is it $6 billion or $6.2 billion or is it $4 billion or $4.5 billion. The bottom line is it's a big number and we're going to have to do a lot of work to even get close to those numbers. So instead of wasting time arguing about exactly what the number is maybe we should spend some more time actually getting projects built.

Our goal should not be to "get projects built" but to have a transportation funding system that makes our people, cities, states and country stronger. While I agree that new transportation funding is needed (you can read my ebook on the subject), new funding without significant reform is worse than no funding at all. We need to continue to oppose all of these funding efforts until serious reform is on the table.

#NoNewRoads

“The Classic Case” was originally published January 19, 2015.