Undermining Prosperity

MEMBER NEWS DIGEST - THE LATEST AND GREATEST FROM OUR MEMBERS' BLOGS

Here at Strong Towns, we spend a lot of our time delineating and illustrating some principles that we believe cities and towns can use as a guide to achieving fiscally sustainable, resilient economic development. These are incremental growth; "chaotic but smart" interventions that are more bottom-up than top-down; recognizing urban streets as platforms for creating value, not just conduits to move cars; and other related ideas.

We argue that the too-common alternative to these approaches is to go all-in on a Ponzi scheme of illusory growth whose way is paved (literally) by debt-financed infrastructure. Cities that do this ultimately undermine their own prosperity and become fragile, susceptible to devastating economic shocks—or simply slow but relentless decline.

This week, Strong Towns member bloggers around the country gave us a number of insightful takes on not so much what their own communities are doing to foster future prosperity, but in many cases what they are doing to (unwittingly) undermine it.

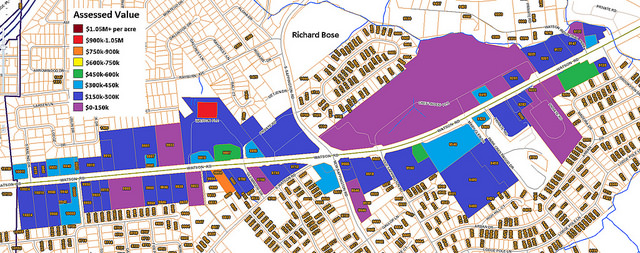

In St. Louis, our friends at NextSTL posted another "Do The Math" analysis of a St. Louis area commercial district, inspired by the brilliant number-crunching of our friends at Urban3. This time their focus is on the small suburb of Crestwood, which draws an unfavorable comparison to the more pedestrian-friendly former streetcar suburb of Maplewood:

The most glaring signal of decline in the area is the shuttered Crestwood Mall. Once assessed at $28.7M in 2006 when open, it is now assessed 89% less. The quick decline of the mall exposes the vulnerability of this type of development. What happens in Maplewood when a establishment closes? People walk past it to the next place until a new establishment opens there. What happens when enough places are empty in a mall? People stop going to the trouble of driving there because one can’t tell how much of it is still occupied from the outside. Once it hits a tipping point, it crashes hard. Now an albatross, the mall sold for $3.5M at auction, and the town is left waiting for the extraordinary amount of capital it will take to bring it back to life or replace it.

Maplewood, Missouri - Image Source: Wikipedia

Could Crestwood (94% white) have more in common with now-nationally-infamous Ferguson than its residents would like to think?

Like Ferguson, Crestwood is being undermined by infrastructure and housing subsidies on the periphery of the region. Without population growth to fill in behind, Crestwood is very vulnerable. It used to benefit from being on Route 66. Now bypassed by I-44 its transportation advantage has slowly eroded as more rely on the interstate to go to and from further away homes.

On the more promising side, NextSTL spotlights a planned new development in St. Louis's Central West End that illustrates how places which still have the "bones" of good urban design can come back to live after disinvestment and decline.

North side of Olive across the street from the proposed development

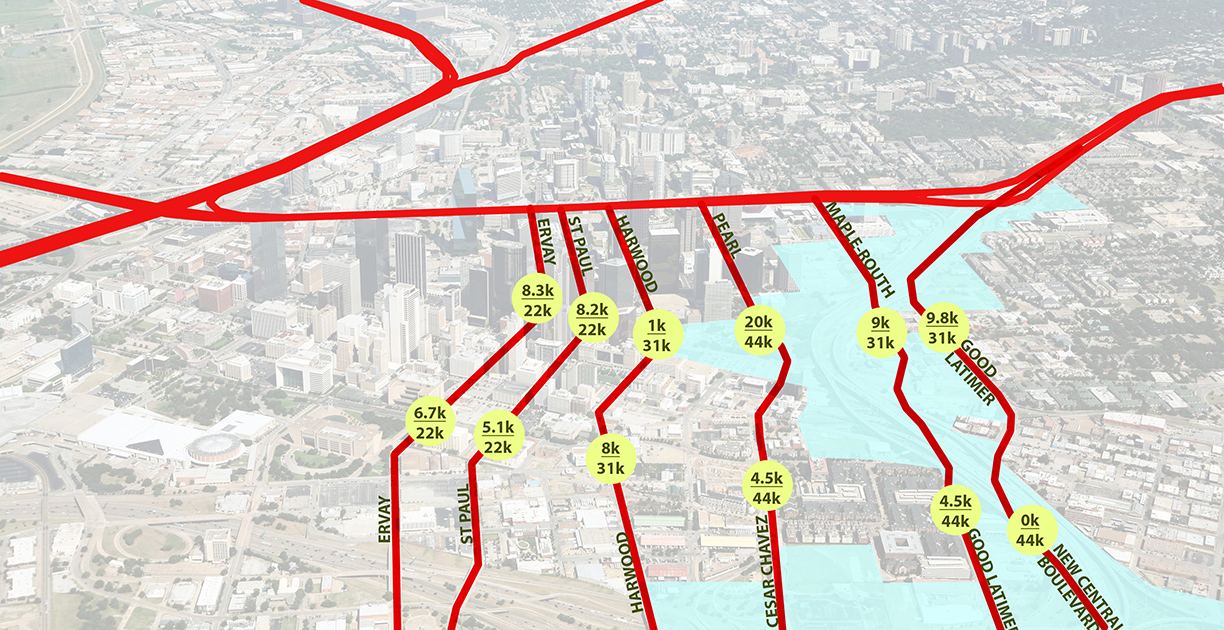

The most common way that U.S. cities tend to undermine their own prosperity is with deeply misguided ideas about transportation. Patrick Kennedy of Walkable Dallas-Fort Worth has had one of these ideas in his sights for a long time now: the idea that urban freeways are necessary for mobility. Writing for D Magazine's StreetSmart blog, he explains how a well-connected urban street grid can handle even more traffic than an elevated expressway, without any of the expressway's devastating effects on neighborhood connectivity or adjoining land values.

Straight through the heart of a city is no place for a high-speed freeway. But these roads do have a time and a place, moving people quickly and safely from one major destination to another. What never has a place, though, is the dreaded stroad: bad at moving traffic, even worse at creating value and productive activity, not to mention dangerous, ugly, and expensive.

Image credit: Design Rochester (modifications by Ron Beitler)

Ron Beitler in Lower Macungie, Pennsylvania, takes these street-road hybrids to task for failing at pretty much everything, but worst of all, for failing at protecting lives:

According to the Governors Highway Safety Association Pennsylvania had the second highest increase in pedestrian deaths from 2013-2014…. Here in the Lehigh Valley a woman lost her life walking on the shoulder of Airport Rd. when she was hit by a drunk driver. The drunk driver will be punished as he should be. But the local officials, planners and engineers who designed and allowed a dangerous STROAD that mixes restaurants, movie theaters, pubs and retail (things people want to and should be able to walk to) with zero pedestrian accommodations will not.

This death like most could have been prevented through better policy, design and practice. More than half of all pedestrian fatalities occur on arterials, and over 60 percent of these tragedies occur on roads with speed limits of 40 mph or higher.

Image credit: Google

Our friend Johnny at Granola Shotgun has been on a roll lately with a brilliant series of posts on the failure of the suburban experiment in California's Antelope Valley. In "Urban Triage", he examines the sheer scale of the problem of overbuilt, underutilized infrastructure in declining suburbs that are increasingly unable to maintain even a fraction of it. His concluding thoughts are hard-hitting and should disturb anyone who cares about the huge numbers of people living in places that our economy is leaving behind:

Here’s the scale of the problem. Each red circle is an intersection that needs to be maintained at a price point that isn’t even remotely going to be covered by the local tax base. Now connect all those red rots with the connecting infrastructure… The numbers simply don’t add up and they never will. The growth phase of this area has come to an end and the maintenance bills are starting to arrive. That takes us back to triage. With scarce resources people need to start asking some tough questions. What gets maintained and what is let go?

I recently spoke to a group of civil engineers and local government representatives. The engineers all looked around and very quickly drew lines on the map. The older parts of town closer to the center were already pretty viable as they were. The newest developments on the edge of town were toast from a cost/benefit perspective and should have never been built in the first place. The stuff in the middle was a toss up. With a little work some of it could be salvaged and some of it will probably fail. Then there were the government folks who deal directly with the public. They looked at the map and explained that the wealthier most politically organized folks live out in the big new homes on the edge of town. The people who live in the older more central neighborhoods are predominantly poorer less educated ethnic minorities. Anyone want to guess how scarce resources are going to be spent moving forward?

When the problem is this massive and daunting, surefire solutions are impossible to find—and yet every community activist knows the experience of being told, "If you don't have a solution to offer, stop complaining." Another Granola Shotgun post suggests the better question to ask is, "Where do we go from here?"

What do places successfully weathering decline look like? Perhaps they look like the Sagebrush Café, in an old gas station in Quartz Hill, CA—before and after images here:

Yet, writes Johnny, our cities aren't doing enough to encourage this kind of reinvention of dilapidated spaces. Indeed, the regulatory environment and local government priorities too often make it the harder road to follow:

Down the road a bit is a brand new retail center with a Starbucks that opened last week. From start to finish the site went from a barren patch of desert to a fully operational complex in six months. That’s about how long it took the gas station to be transformed into a cafe – on paper. Notice the difference in the scale of these two projects.

It's projects like this, though, that might be the only hope of places like the Antelope Valley, no longer desirable or booming enough to sustain more waves of outward expansion:

The space ships full of cash aren’t coming. The growth phase is over. The problem is the town built entirely too much cheap scattershot crap on a giant and very expensive infrastructure chassis. What this town really needs is an army of small local shopkeepers and micro-producers to fill the voids left behind by years of flimsy hollow growth.

The Sagebrush Café vs. Starbucks contrast is the kind of thing that feeds the perception, shared by many a local activist in many a city, that the local government process is rigged in favor of a well-connected minority. Sometimes these advantages are subtle. Sometimes they are blatant. On the blatant end of the spectrum is this story, shared with us by Cathy Antunes in Sarasota, Florida, where a county commissioner is moonlighting as the executive director of a nonprofit foundation that—you guessed it—routinely lobbies the county commission!

Who gets lost in the shuffle? Bruce Nesmith in Cedar Rapids examines the lack of focus on poverty in the city's comprehensive plan.

If affordable housing is far from jobs, it creates as many problems as it solves.

For many people in American society, the poor are simply invisible. Auto-oriented development, notes Eric O. Jacobsen (The Space Between, Baker Academic, 2012, p. 42), "has increased the distances at which we encounter one another.... And because of the large parking lots and wider streets that are needed to accommodate all of those cars even when we are engaged in the same activity in the same place, the distance between us has increased significantly." A more atomized society harms us all in some way or other, but has especially negative impacts on the lives of those at the margins.

There are lot of damaging assumptions and practices out there that are undermining our own cities' prosperity, their fiscal solvency, and ultimately, their ability to provide a decent quality of life for their residents over the long term. It's going to take a sustained, ongoing effort to change minds—but a lot of our valued members are working hard at it in their own ways in their own communities. Even if we don't know what all the right things are to do, we can all start by insisting that those who represent us stop doing the wrong things.

You can check out the entire member blogroll on the Strong Towns member site. If you're a member with a blog and would like your work to show up there, please let us know about it.