Making The Case For Equality

Eli Damon is a Strong Towns member and cycling activist who came to biking because of a visual impairment that prevents him from driving a car. (Check out our podcast interview with him to hear more.) Today, he shares an extended essay about his journey toward improving bike ordinances in his town and advocating for safe cycling in the flow of traffic (rather than on the side of the road or in a separate bike lane).

This essay was originally published on IAmTraffic.org and is republished with permission (edited for length). Visit IAmTraffic.org for more resources about cycling rights and safe cycling.

I live in Easthampton, Massachusetts. Late in 2011, I began an effort to remove discriminatory language from my city’s bicycle ordinances, an effort that concluded late in 2012. As part of the effort, I attempted to educate city officials, most of whom had little knowledge of or interest in cyclists’ right to the road, about the true nature and consequences of these laws. As a result of my attempt, I was able to greatly expand and refine the way I explain these topics.

Laws That Discriminate Against Cyclists

“Bicycles must be considered and treated as equal road vehicles and bicyclists must be treated as full and equal drivers of vehicles in traffic laws and policies. Inequitable laws, which discriminate against bicyclists compared to other road users by allowing non-uniform local regulation, restricting access or movement must be repealed. ”

Click to view larger

Every state in the United States has a law that initially grants those traveling by bicycle all of the rights enjoyed by those who travel by motor vehicle, or by vehicle in general. And every such law goes on to make broad exceptions to this rule. Some of these laws, in acknowledgement of the exceptions’ breadth, go on further to make exceptions to the exceptions. These laws often restrict, beyond what is required of other drivers of vehicles, the roads a cyclist can drive on and the position on a road that a cyclist can occupy. They can also require or prohibit certain equipment.

These laws tend to be vague and arbitrary. Some states permit municipalities to impose further restrictions. The map on the right, provided by Dan Gutierrez, shows which states permit local traffic regulations and which states guarantee uniform statewide traffic regulations.

Many of the city ordinances that concerned me were contrary to the Massachusetts traffic code. (I use the term “code” loosely, as Massachusetts statutes are notoriously disorganized.) This raised a debate over whether Massachusetts law permits municipalities to enact their own traffic regulations. I, along with a number of my colleagues, am under the impression that Massachusetts does not permit local traffic regulations, and that is what I argued. However, some have expressed a contrary opinion, and I have been unable to find a clear demonstration of either position.

The Far Right Rule

By far the most problematic of all common elements of bicycle laws is what I call the “Far Right Rule”, also known as “(As) Far Right As Practicable”, “AFRAP”, “FRAP”, “Far To Right”, and “FTR”. The National Committee on Uniform Traffic Laws and Ordinances (NCUTLO), “a private, non-profit membership organization dedicated to providing uniformity of traffic laws and regulations through the timely dissemination of information and model legislation on traffic safety issues,” (defunct as of 2008) expresses the Far Right Rule in its last (2000) version of their Uniform Vehicle Code (UVC) as follows:

“Any person operating a bicycle or a moped upon a roadway at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall ride as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway.”

11-1205 Position on roadway

(a) Any person operating a bicycle or a moped upon a roadway at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall ride as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway except under any of the following situations:1. When overtaking and passing another bicycle or vehicle proceeding in the same direction.

2. When preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road or driveway.

3. When reasonably necessary to avoid conditions including, but not limited to, fixed or moving objects, parked or moving vehicles, bicycles, pedestrians, animals, surface hazards, or substandard width lanes that make it unsafe to continue along the right-hand curb or edge. For purposes of this section, a “substandard width lane” is a lane that is too narrow for a bicycle and a vehicle to travel safely side by side within the lane.

4. When riding in the right turn only lane.(b) Any person operating a bicycle or a moped upon a one-way highway with two or more marked traffic lanes may ride as near the left-hand curb or edge of such roadway as practicable.

Click to view larger

Many state vehicle codes include similar language, and in those states the language has caused great confusion, conflict, hardship, and expense for bicyclists. The map on the right, provided by Dan Gutierrez, shows which state traffic codes include far right rules and which do not.

My home state of Massachusetts does not have a far right rule. The city ordinance that concerned me most, the one that inspired and motivated my effort, was a far right rule. At the time, city ordinance, Section 3-41 read as follows:

Every person operating a bicycle upon a roadway shall ride as near to the right-hand side of the roadway as practicable, exercising due care when passing vehicles or approaching vehicles proceeding in the same direction.

Problems with the Far Right Rule and other related language were recognized at least as early as the implementation of a far right rule in California in the early 1970s. California lawmakers sidestepped the problems by adding on many qualifications and exceptions to the rule, and more have been added since then (see the UVC excerpt above). In fact, with so many exceptions, the rule rarely applies, but that does not eliminate the problems. As early as 1975, NCUTLO’s bicycle subcommittee issued a report pointing out these problems and recommending removing the language from the Uniform Vehicle Code, although the full committee voted by a narrow margin not to take their recommendation. (Information about the history of the UVC was gathered through a conversation with Bob Shanteau, who has tracked down and reviewed primary source documents.)

So why is the Far Right Rule so problematic?

1. It is confusing. Few people are familiar with the word “practicable”, its meaning or implications for the law. Instances of the Far Right Rule that include qualifications and exceptions are long and complicated. It is difficult for most people to follow or remember them. The term “substandard width lane” is used idiosyncratically, and a whole other sentence is included to explain it.

“This accords with the common attitude that roads are for cars. Bicycles are toys, not real vehicles. Cycling is a frivolous activity, and cyclists have no compelling need to use the roads, or to use all features of the roads.”

2. It is vague. Few people have the expertise needed to competently judge what is and is not a practicable position for a cyclist to occupy, what constitutes an unsafe condition, when moving left helps to avoid one, or how wide a lane is needed for a bicycle and a “vehicle” (the UVC and many state vehicle codes explicitly define “vehicle” as excluding bicycles) to travel safely side by side within it.

3. It is prejudicial. Most people (cyclists, motorists, police officers, etc.), assuming they are aware of a far right rule in their jurisdiction, interpret the rule not by its technical implications, but by its overall message, especially if that message accords with their own attitudes and beliefs. Exceptions and qualifications aside, the overall message of the rule is that cyclists must stay to the right. That is the #1 priority, the law insinuates.

This accords with the common attitude that roads are for cars. Bicycles are toys, not real vehicles. Cycling is a frivolous activity, and cyclists have no compelling need to use the roads, or to use all features of the roads. Bicycles don’t belong on the road but can be tolerated as long as they stay out of the way. It accords with the belief that going slow is dangerous and that closer to the edge is always safer if you’re going slow. Through its vague and confusing language and its insinuation of priority for motorists over cyclists, the Far Right Rule begs to be misinterpreted by those who would see a cyclist riding confidently in line with other traffic and think, “That’s so wrong. It can’t possibly be legal.”

A New Home, A New Discovery

"The road is for the cars. You've gotta stay on the side of the road." -Police sergeant

"The road is for everyone." -Eli

I moved to Easthampton, Massachusetts, from nearby Amherst, in July, 2011. In November, 2011, I had an unpleasant encounter with an Easthampton police officer, who did not acknowledge my legal right, as a cyclist, to use the road in the same manner as a motorist. I have had similar conflicts with police officers in other departments, and some of them escalated to extremes. Fortunately, this one did not.

When I reported the encounter to my friends, one, a fellow cyclist and Easthampton resident, wrote a letter of complaint to the police chief. He shared the chief’s response with me. The chief’s response was a non-sequiturial reference to city ordinance Section 3-41. The ordinance had no direct bearing on the conflict. The officer had never even accused me of violating it. From there, I read the city’s bicycle ordinances thoroughly. I found the entire body of bicycle ordinances to be replete with problems.

I contacted my ward representative to the City Council and voiced my concerns. As it turns out, he is also a cyclist, and he had his own concerns about the ordinances. He invited me to write up my concerns and send them to him. As it turns out, he is also the chair of the ordinance committee. He agreed to have the committee review the bicycle ordinances. With the help of another friend, who is also a fellow cycling instructor and Easthampton resident, I turned my complaint into a proposal.

Over the next several months, I met with the ordinance committee to discuss my proposal. In these discussions, they concurred with me on many of the more minor problems, but they repeatedly put off discussing my greatest concern, Section 3-41, what I call the “far right rule.” I got the sense that the notion of repealing the far right rule would be controversial because the committee, like the general public, was not all that enlightened about the issues for cyclists regarding lane position. I would have to educate them. Toward this goal, I gave a presentation to the committee on the subject of lane position for cyclists. I am quite proud of the result and am fortunate that it was recorded so that I can share it with you.

Presenting the Case

I. The Role Of Traffic Regulations

A bicycle is a vehicle. A cyclist is a driver of a vehicle. It is important to acknowledge this from the start because it has implications that surprise, and even offend, many people. But it is true under the common meaning of the word “vehicle”. Moreover, every jurisdiction either explicitly encodes this fact into law or makes a technically equivalent declaration.

This is important because the Rules of the Road, the basic principles on which traffic laws are based, are what they are because of the general characteristics of roads, vehicles (how they move) and of people driving vehicles on roads (how they perceive and react to their environment). Bicycles, cars, and many other vehicles possess all of the characteristics that make the Rules of the Road effective in facilitating safe and convenient travel. The Rules of the Road were formulated at the beginning of the 20th century, when the dominant vehicle was the horse-cart. They were adapted from rules for waterways, which are far older. We often take them for granted now.

What do we expect of traffic regulations? Please excuse my presumption, but I will speak for all of us on this. As you read this, think about how actual traffic regulations accord with these expectations. Try to imagine what traveling would be like if traffic regulations did not meet these expectations.

Photo by Richard Masoner

We expect traffic regulations, like other laws, to be clearly specified. We want to know precisely what acts are lawful and what acts are unlawful, so that we can be sure to act lawfully, and so that can defend ourselves against accusations of acting unlawfully. We also want to be sure that others clearly understand what the law requires, so that they can act lawfully, so that they can be held responsible for acting unlawfully, and so that they cannot mistakenly accuse us of acting unlawfully.

We expect traffic regulations to be uniform over large areas. Most laws pertain to what we do in one particular place. But driving is about moving from place to place. We often pass through many jurisdictions on a single trip. Learning and remembering many different sets of rules, frequently switching from set to set, keeping track of which set to use when, researching new sets of rules before traveling to and through new jurisdictions—we would probably find this to be extremely burdensome. It would render us quite vulnerable to accusations of acting unlawfully: What did I do? Did I break the law? What law? What jurisdiction? Was it an accident? How can prove it was an accident?

We expect traffic regulations to be the same for all drivers and all vehicles. Again, we don’t want to have to learn different sets of rules for driving different types of vehicles. We also want to be able to readily anticipate what other drivers will do, readily enough for it to be instinctive. We want to be able to do this under a wide range of conditions, including at long distances, at high speeds, and in darkness. Hmmm, let’s see. What kind of vehicle is that? It’s a ?-mobile. And what is the rule for a ?-mobile in this situation? I remember. No, wait. That’s not it. Oh, right, the rule is–

We expect traffic regulations to be compatible with the way vehicles move and the way people perceive and react to their environment when driving. For example, the rules should not require us to move from side to side because vehicles can’t generally do that. The rules should have us focus our attention toward the front most of the time, not the rear or side, because people are not made to focus their attention to the rear or side, particularly while moving. This is why other drivers are required to yield to us when approaching us from our rear or side, but we must yield to other drivers in front of us.

We expect traffic regulations to offer us trust and flexibility. Conditions on the road are dynamic and complex. No one but us, as the drivers of our respective vehicles, is in as good a position to assess our circumstances and to choose the best course of action. We need to have the flexibility to do what conditions demand. Lawmakers must not attempt to micromanage our actions before the fact. They must trust us to respond to conditions that only we, not they, experience.

We expect traffic regulations, like other laws, to solve more problems than they create. A rule that isn’t part of a solution is part of a problem. We expect the law to respect our dignity and liberty by imposing no more limitations on us than is necessary to solve a genuine and compelling problem, with side effects that are substantially milder than the original problem. We expect the arguments connecting cause (problem) to effect (solution) to hold up to rigorous intellectual scrutiny.

II. Positioning Narrow Vehicles

While most vehicles have the basic characteristics of vehicles that make the Rules of the Road what they are, vehicles are distinguished from each other by many additional characteristics, and driving a vehicle of a particular type comes with additional issues beyond those of driving in general. One such characteristic shared by a very substantial class of vehicles is that of being narrow (or substantially narrower than is typical). To the right, you can see some examples of narrow vehicles.

When driving a vehicle of close-to-typical width, people rarely think about their lateral position on the road. But when driving a narrow vehicle, choosing a position is far more complex and far more critical then when driving a wider vehicle. With a narrow vehicle, there are more options to consider and the decision has greater consequences. Advantages of a good position include:

- avoiding stationary hazards,

- being able to travel along a predictable course,

- having a clear view of the road ahead and around corners,

- noticing and reacting to changing conditions early,

- being readily noticed and correctly judged by others,

- discouraging dangerous maneuvers by others, and

- having room to maneuver around or escape from hazards that take you by surprise.

Likewise, disadvantages of a bad position include:

- encountering more stationary hazards,

- being prone to making erratic maneuvers,

- having an obstructed or cluttered view of the road ahead and around corners,

- being prone to overlooking or reacting poorly to changing conditions,

- being easily overlooked or misjudged by others,

- encouraging dangerous maneuvers by others, and

- having no room to maneuver around or escape from hazards.

Here is a list of factors that influence a cyclist’s choice of position:

- DESIGN – curvature, configuration of lanes (i.e. number/direction/ destination), lane width, edge features (e.g. parked cars, shoulder, curb, guardrail, signs, trees, rumble strip), driveways/intersections (e.g. frequency, size, busy-ness), intersection designs (i.e. sight lines, merges, diverges, turn lanes, slip ramps, traffic lights), approaching changes

- SURFACE – facilities (e.g. sewer covers, storm drains, expansion joints, demand actuated traffic signals), damage (e.g. potholes, cracks), foreign material (e.g. water, snow, ice, sand, gravel, tree debris)

- WEATHER – precipitation (e.g. rain, snow), ambient light (e.g. darkness, low sun), wind

- TRAFFIC – other drivers’ speed, vehicular traffic volume, possible pedestrian traffic, possible pedestrian-like vehicular traffic, animals, motorist behavior trends

- CYCLIST – bicycle equipment, destination, speed, familiarity with road

I meant what I said about it being a complex decision. Fortunately, it is usually an intuitive decision rather than an intellectual one. The skill of choosing a good position is improved with training and practice. Take a look at the conditions on the roads in your area. Try to identify those that might influence the choice of position for a driver of a narrow vehicle.

Driving too close to the edge is dangerous and burdensome. For safety and convenience, cyclists should stay well away from the edge. Sometimes this means being in the middle, or even on the left side, of a lane. Sometimes it means being in a lane other than the rightmost lane. Watch the animation below for a demonstrates.

How do we decide what the best position to take is? As I said before, traffic is dynamic and complex. There are many factors that influence the decision. Hence, there can be no simple rule or algorithm for determining the best position. It can only be made by someone who is present and fully aware of the conditions. And conditions can change rapidly. There is no time to apply a rule or algorithm that accounts for all factors, even if one could be formulated. While the decision can be evaluated intellectually after the fact, it must be primarily an intuitive decision. Also, the knowledge, training, and experience needed to select a good position or competently evaluate one after the fact are frustratingly rare. A cyclists position should not be evaluated before the fact, and it should not be evaluated by any of the majority who lack the necessary knowledge, training, and experience.

While there can be no rule or algorithm for choosing the best position, there is one very important guideline. More adverse conditions demand a more assertive position. Let me repeat that because it is important: More adverse conditions demand a more assertive position.

Occupying more space is almost always safer. It is only a question of how much is enough.

III. The Role Of Courtesy

So if it is safer and more convenient for a cyclist to keep away from the edge, what obligation does a cyclist have to make room for other drivers pass? Regardless of what ill-conceived and carelessly drafted laws might insinuate, your first priority as a driver should be safety. You should always drive defensively. Your second priority should be your own convenience.

You have the right to travel on public roads, and you have the right to a trip that is as easy and carefree as anyone else’s trip. You should feel free to exercise that right fully. You should not curtail your exercise of that right for what is usually the trivial or imaginary convenience of another. Your third priority is courtesy. You should facilitate passing when it is safe and convenient. Laws and norms sometimes implicitly penalize caution or efficient travel for cyclists. These laws and norms should be resisted. We should not penalize cyclists for using caution or for traveling efficiently, as long as it is done with caution.

When you, as a cyclist, want to determine whether you should move over, you should ask yourself the following questions. If you answer YES to all of them, then by all means, do the courteous thing and let others pass you.

- Are other drivers present? AND

- Do they want to pass? AND

- Are they currently unable to pass safely? AND

- Are they refraining from passing? AND

- Is it likely that they will be unable to pass safely for a substantial period? AND

- Would they be able to safely pass right away if I were to change position? AND

- If they passed me, would they then be able to move freely? AND

- Would my new position be safe and convenient for me to travel in? AND

- Would my new position be safe and convenient for me to move to now?

An argument I had earlier compels me to point out that it is not safe to change your position until you fully assess the situation, yield to anyone you are required to yield to, communicate your intention to other drivers, and achieve confidence that they will not interfere with your move or make any sudden moves of their own. This takes at least a few seconds under the mildest of conditions.

In this video to the right, you can see an excerpt from a presentation I gave, which explains the control and release technique.

It is important to understand that cyclists and motorists (and other travelers) largely want the same things. They want get where there are going safely and conveniently. They want to share the road cooperatively and harmoniously with their fellow travelers. Cyclists do not want to make anyone’s life more difficult. If anything, they tend to be overly accommodating at the expense of sacrificing their own needs. They even tend to make concessions that offer no practical benefit to anyone else, just to avoid conflict. They want to help others whenever they reasonably can.

The narrowness of a bicycle gives its driver a special ability to facilitate passing, which drivers of wider vehicles do not have. They are almost always happy to use that special ability when doing so does not involve sacrificing their own needs. Other vehicles give their drivers other special abilities, which can be used to help others. But the special ability offered by a bicycle is treated differently. Cyclists’ special ability is often used against them. They are often pressured or bullied into using that ability to help others at the expense of sacrificing their own needs. A cyclist who moves over to help us pass could have decided that it was too dangerous or too inconvenient, or they could have decided to drive a wider vehicle. We should not resent cyclists for being in the way. We should appreciate that they selected a vehicle that, unlike many others, often gives them the ability to get out the way. When they use that ability to help us pass, we should recognize that they did so for our benefit.

IV. Effects Of Discriminatory Laws

Discriminatory laws put those who would travel by bicycle in a vulnerable position. They can render safe and effective bicycle travel unlawful or legally ambiguous. Or they can subject cyclists’ behavior to excessive scrutiny, so that they must anticipate being called to defend their behavior at any time. Lawmakers’ failure to unequivocally affirm the right to travel by bicycle (or by any simple means, for that matter) contributes to harassment by motorists and police officers and hinders justice for cyclists who are harassed or who are involved in a crash.

“Few police officers receive any substantial training in effective cycling or bicycle law enforcement (a major problem for cyclists), let alone what would be needed to judge something as subtle as a cyclist’s position. ”

Discriminatory laws that use confusing, vague, or prejudicial language can foster widespread misinterpretation of the law by public officials of all kinds, including police officers, as well as motorists generally, and even cyclists themselves. They frustrate the efforts of cycling educators to teach defensive driving techniques. Laws that use vague language implicitly dump the responsibility for interpreting them primarily on police officers and secondarily on prosecutors, judges, etc., a responsibility that they are not necessarily prepared to handle. This is the case with the vague language, “as near to the right-hand side of the roadway as practicable,” from the old Easthampton ordinance Section 3-41. In fact, few police officers receive any substantial training in effective cycling or bicycle law enforcement (a major problem for cyclists), let alone what would be needed to judge something as subtle as a cyclist’s position. This makes cyclists who drive defensively legally vulnerable.

Using bicycles for transportation offers vast benefits. It should be encouraged, not discouraged. Many people (including me) rely on bicycles as a means of transportation. Many of them could greatly enhance their lives by learning to use those bicycles more effectively. Many more people could greatly enhance their lives by replacing some or all of their travel using mass transit or personal automobile by cycling, assuming that they were made to feel comfortable using defensive techniques. These changes can make travel quicker, easier, more reliable, more flexible, less stressful, and less expensive, thus enhancing the possibilities for homes, education, jobs, shopping, health care, entertainment, socializing, political activity, and/or capital investment. For those who make the change, it opens up new dreams and ambitions and elevates their overall quality of life.

Beyond the benefits to individuals, using bicycles for transportation offers vast benefits to communities, governments, and societies. More cycling leads to less use of motor vehicles, which leads to to less congestion, less demand for motor vehicle parking, fewer crashes, less environmental and noise pollution, and less money diverted from the local economy. Expanding people’s options in life leads to more economic and cultural productivity, and hence more tax revenue. Fewer crashes leads to less public expense for health care and emergency services. Safe cycling behavior leads to less stress and conflict for everyone on the road.

However, discriminatory laws often prevent these benefits from being realized. Legal vulnerability makes cycling in a safe and convenient manner more stressful. Such laws can discourage people from cycling in such manner. Those who have other transportation options may be discouraged from cycling entirely. Even those who have no inclination to travel by bicycle are deprived of the public benefit of bicycle transportation.

V. The Result of My Effort

I consider my effort to amend the Easthampton bicycle ordinances a success. The ordinances were, in fact, amended as a result of my work, and all off the changes were positive. However, I did not get all of the changes I wanted. There will be opportunities for further changes in the future.

Section 3-41 was not repealed, but it was changed. Whereas it previously read:

Every person operating a bicycle upon a roadway shall ride as near to the right-hand side of the roadway as practicable, exercising due care when passing vehicles or approaching vehicles proceeding in the same direction.

it now reads:

Every person operating a bicycle upon a roadway shall ride as near to the right-hand side of the roadway as is safe, unless, preparing to make a left turn, riding in a lane which is too narrow to share safely, avoiding degraded street surfaces (“broken pavement”) and sewer grates, avoiding the “door zone” of parked automobiles, avoiding obstructions such as pedestrians and stopped vehicles or avoiding debris which could damage the bicycle or degrade handling (sand/gravel/glass).

The word “practicable” has been replaced with “safe”, and some exceptions have been added. I have some concern that the changes give an air of legitimacy to an inherently illegitimate rule. For this reason, I did not participate in drafting the new ordinance.

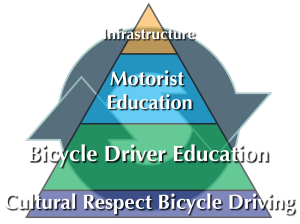

But changes to the ordinances is not the only result, or even the most important one. I believe that the greater success was in using the ordinances as a platform to educate and raise consciousness about cycling, paving the way (no pun intended) for future improvements not only in law, but in culture as well. And as the pyramid to the right indicates, we cannot change behavior without changing culture.

For more information about my effort to reform the Easthampton bicycle ordinances, see my article Partial But Definite Success Amending Easthampton Bicycle Ordinances.

(Top photo by Dave Fayram)

Related stories

About the author

Eli on his bike (Photo from IAmTraffic.org)

Eli Damon is principally a math teacher. He has a B.E. in computer engineering from SUNY Stony Brook and a Ph.D. in mathematics from Umass Amherst (2008). In the Society for Creative Anachronism, he is Lord Eli of Bergental, member of The Order of the Fountain. Due to a visual disability, he cannot acquire a driver’s license. He once thought of this limitation as a severe one. He made some trips by foot, bike, and bus, and relied on friends and family members with cars to give him rides for some other trips. For the most part, however, the difficulty he had in traveling prevented me from living what most people would consider a full life. He learned to drive a bike at age 27, and it radically transformed his life: "Suddenly, I could go wherever I wanted, whenever I wanted, in a reliable, flexible, carefree manner. It felt as if I was no longer disabled. Now I travel almost entirely by bicycle. I have found that good cycling habits provide me with more freedom and flexibility than I could ever achieve through driving a motor vehicle. I have cycled in ten states and the District of Columbia, on a wide variety of roads under a wide variety of conditions. I have made trips of up to 200 miles."

You can find more of Eli's writing on IAmTraffic.org.