Suburban Poverty: Hiding in Plain Sight

There is arguably no place where half a century of suburban growth has more resembled a giant Ponzi scheme than in Florida. The state of Florida went all-in on the suburban experiment in a way that few other places did. For reasons that may have more than a little to do with the advent of air conditioning, the state's population did not begin to grow rapidly until the post-WWII era, when the economic and public policy forces driving suburbanization were at their peak. Add a state economy driven by land speculation and lax-to-nonexistent development regulations, and you've got yourself a perfect storm.

Florida soon became the poster child for disastrously unsustainable development—both fiscally and environmentally. Unsurprisingly, boom-and-bust cycles tend to hit the state hard. The suburban experiment has been most ruinous in precisely the places that were first to embrace it, and that embraced it with the most reckless abandon.

Narrative accounts of the fallout of Florida land scams and ill-conceived development are legion. But if you haven't been to this part of the country, you may not know what the fallout looks like. "Suburbia will be the new slums" may be something you've heard or read in urbanist circles but not yet encountered a preview of on the ground, because there's really nothing comparable in the Midwest or Northeast. In 2016, fringe exurban communities around Minneapolis-St. Paul, where I grew up, are still affluent and exclusive places, while poverty is growing fastest in inner-ring suburbs. Not true in the boom-and-bust Sunbelt.

Let's take a field trip to Southwest Florida, which was hit as hard as anywhere in the U.S. by real-estate market collapse and foreclosure crisis that began in 2006. If you Google "foreclosure ground zero" and scan the first few pages of results, you'll find many claimants to the (dis)honor, but Lehigh Acres and Cape Coral are two names that show up again and again.

This is a satellite view of Cape Coral, a large suburb of Fort Myers. Founded in 1957 and intended as a retirement community, its population has more than doubled since 1990 to over 150,000 residents, and residents under age 25 now outnumber residents over 65.

Cape Coral was built at a breakneck pace by its developer, the Gulf American Corporation. In a pattern you see over and over in Florida—which boggled my mind when I first moved there—the developer paved huge swaths of the street grid before most of the lots were even sold, let alone homes built. The result is this:

Florida is infamous for "zombie subdivisions" like this, where rudimentary infrastructure exists but the promised boom never came. There are those (many of them realtors) who will tell you it's still coming. This may be the decade! The future is bright! You can have your affordable home amid sunshine and palm trees and relax on Easy Street!

Don't count on it.

This is Lehigh Acres, located east (inland) from Fort Myers. Its population has more than quintupled between 1990 and 2010, from 13,611 to 86,784. The population is young and relatively low-income.

Notice the scale here. Lehigh Acres is huge. It occupies about 95 square miles, twice the land area of San Francisco or Boston. It's hard to overstate the extent of these master-planned, pre-platted Florida developments, and it's hard to comprehend their sheer mind-boggling scale unless you've been there.

Like northwestern Cape Coral, much of eastern Lehigh Acres is mind-bogglingly empty:

Harper's magazine did a fascinating piece on Lehigh Acres's sordid history a few years ago. It's worth a read:

"In the annals of real estate marketing, Lehigh Acres is legend. In the history of urban planning, it was apocalyptic."

Here, a bit to the north, we find the adjoining cities of Port Charlotte and North Port, halfway between Sarasota and Fort Myers (about 40 miles from each). North Port's per capita income is $16,836, far lower than the $28,326 for Sarasota County, which it belongs to. The population averages about a decade younger than the county as a whole (which is famously a retirement destination), and half of all households have children. By now you're getting the picture.

These are not cities that even existed pre-WWII; they have zero traditional neighborhoods. They were wilderness in 1950. But nor are they the elite, affluent exurbs that surround most Midwestern and Northeastern cities. They were never built to be. They were built to provide vast, almost unimaginably vast, swaths of cheap real-estate and low-quality tract housing to buyers with access to a mortgage market awash in easy credit.

These places were hit hard by subprime and predatory lending in the 2000-2006 period, and the fallout was predictable. In North Port, the tax base dropped 59 percent from 2007 to 2011.

An interactive map from Zillow lets you view the rate of underwater mortgages (negative equity) by zip code in the region. A couple of the worst-hit zip codes are in urban core areas of Sarasota and Bradenton—traditional high-poverty neighborhoods whose residents are largely nonwhite. But many of the rest are in these massive exurban developments (and, as the map shows, in the rural interior of the state, but the economic factors at play are different there):

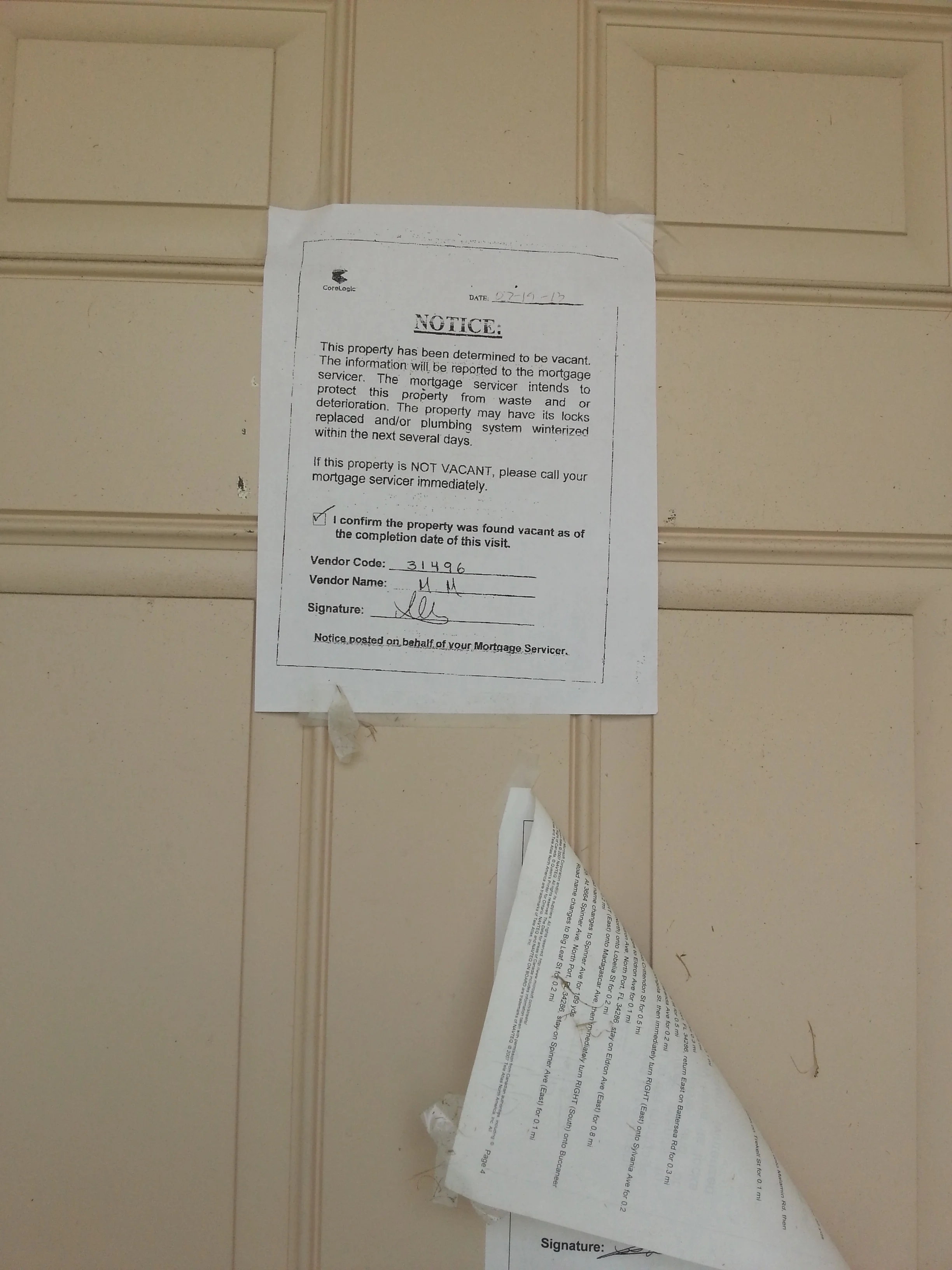

Foreclosures are no longer happening at the rate they were a few years ago, but there's still a large inventory of vacant homes sitting around. You can see signs like this on doors if you pay attention.

A typical residential area in these suburban developments looks like this. Houses are few and far between. The whole city is still less than 1/3 built out:

Zombie subdivisions are a big problem for the homeowners stuck in them. In many cases, the up-front infrastructure cost for these developments was funded with a CDD: Communtiy Development District. This is an entity created by the developer and authorized to sell bonds to pay for street paving, lighting, sidewalks, etc. The residents, once enough of them move in, pay an annual assessment to pay back the CDD bonds.

But what if the market crashes and the promised residents never do move in? The Sarasota Herald-Tribune ran this exposé in 2013 about a zombie subdivision in North Port with a failed CDD:

Only two dozen homes exist in what was to be a 1,999-home, master-planned community. The homes are separated by undeveloped tracts of high weeds that residents say attract snakes, field mice and wild boars.

Trespassers illegally dump debris on empty lots.

The streetlights are shut off, compelling drivers to use their high-beam headlights at night so they can negotiate the development's meandering lanes.

The palatial, Tuscan-style clubhouse stands eerily empty and only partially built — without the promised library, media center, fitness club, steam and massage rooms, crafts room, and billiards and card room.

Astonishingly, at the worst point of the recession around 2010, an expert on the CDD bond market, Richard Lehmann, estimated that 73 percent of Florida CDDs were in default.

This isn't rocket science. This is, "We built this stuff assuming people would come, they didn't come, and now we have no idea how we're ever going to pay for it."

Suburban Poverty: Hiding in Plain Sight

Even the built-up areas in these exurban boomtowns have an aging, dilapidated housing stock and high poverty rates. I paid a visit to one census tract in Port Charlotte, Florida (the older counterpart to North Port, across the county line in Charlotte County), because data showed it had the highest rate of poverty and mortgage foreclosures in the area. It looks like this:

The thing about suburban poverty is that, unlike urban poverty, it hides in plain sight. These are not horrific images of blight. But the overriding sense I had while exploring was of an eerie quiet. Many of these houses seem to be vacant. I can't tell how many only seem that way because their residents are seasonal—but this was February, when the vast majority of seasonal Florida residents are there.

Some homes are in minor disrepair. There is a vacant lot here and there. Some homes are bank-owned. The cars parked in front yards and driveways are beat-up and old.

I didn't get to talk to anyone about the neighborhood, because I barely saw anyone. There is an overriding sense of isolation. And in fact, the experience of poverty in such an environment is one of isolation... from the resources you need to get back on your feet.

Remember what I said about living on Easy Street? I wasn't joking:

If you walk down Easy Street, in the poorest neighborhood of Port Charlotte, to its intersection with Tamiami Trail, the area's main commercial drag, you encounter this bleak scenery.

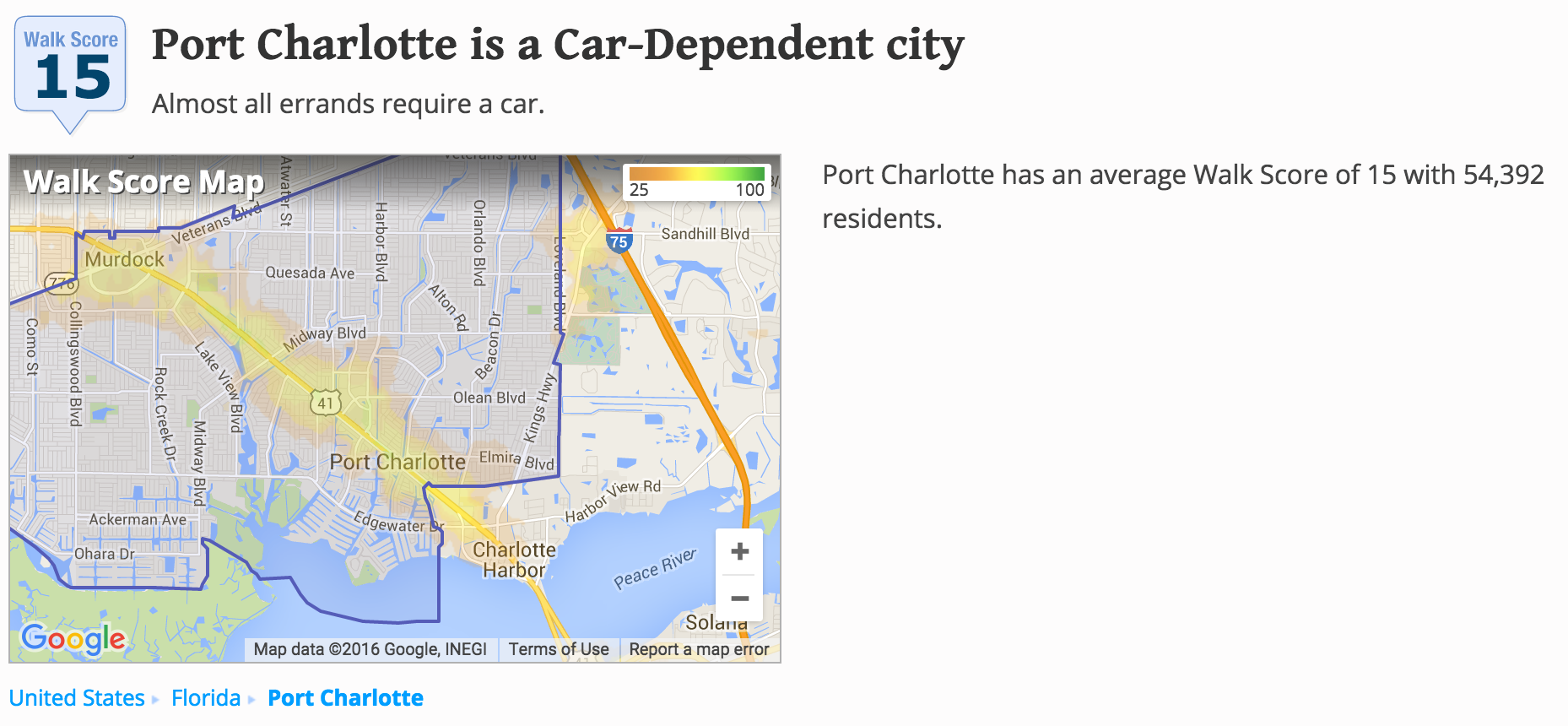

The area gives new meaning to unwalkable. You can get nowhere safely or pleasantly on foot. Walk Score bears this perception out with data:

Commercial areas are dominated by strip malls in various stages of decline. There is a large mall a couple miles away which seems to be hanging on for now, but has some conspicuous vacancies even within it.

The only jobs in sight are low-wage ones in the service industries. The white-collar jobs are in Sarasota or Ft. Myers, both of which can be an hour or more away in peak traffic.

A map from the Census Bureau's OnTheMap web site — an interactive way to look at employment statistics broken down by location and industry — shows how the jobs paying more than $3,333 a month, or $40,000 a year, are concentrated in the urban cores of Sarasota and Bradenton. Not much white-collar work to be had in North Port. (What exists is largely in the medical field, naturally a big industry anywhere you have a lot of retirees.)

So you bought a house out here because it was cheap, much cheaper than closer in in Sarasota. But now you need to be a 2 or 3 car household and commute dozens of miles a day. The simple logistics of life - get the kids from school, get to the doctor, etc.—may be a challenge. There is virtually no transit, and what there is goes virtually nowhere useful.

North Port, and even older and more decrepit Port Charlotte, are not slums. Most of the area is solidly middle-class. But it wouldn't take much to send a place like this over the edge. Or a family in a precarious situation in a place like this over the edge. Imagine something causes gas to return to $4 per gallon instead of $1.60. Imagine the havoc that would wreak on a low-income family's budget in a place where driving vast distances is as unavoidable as it is here.

And the public realm is a disaster. North Port streets are crumbling. And there are a lot of them: 822 miles of streets for 60,000 people. Most of the city is characterized by incredibly low densities, with only one or two houses on many blocks. How on earth are they going to maintain their infrastructure? (Hint: they're not.)

Ah, but perhaps I'm not giving enough credit to the amenities the area has to offer its young families. Look at this beautiful regional park on Google Maps. Imagine taking an after-dinner stroll to it from one of the, uh, many homes in the vicinity:

Water issues are also a challenge. Most North Port residents are on well water, and many are dealing with quality issues and clamoring to be hooked up to city water.

But the cost of bringing services to developed neighborhoods is challenging in pre-platted communities like North Port, Port Charlotte, Port St. Lucie and Cape Coral, North Port Utilities Business Manager Jennifer Desrosiers said.

“Several years back it was estimated it would cost more than $2 billion to get water and sewer for the entire city,” she said.

Who's going to pay for that?

Do any population growth projections support the idea that these cities will reach build-out? Not a chance.

So the roads will continue to crumble. The houses will not age well, because they were built cheaply to begin with. This is already bargain-basement real-estate, not a destination. North Port's selling point—and that of Cape Coral, and Lehigh Acres, and so much of remote exurban Florida—has always been that it's cheap, not that it's desirable or exclusive.

Cheap can only get you so far. Odds are a lot of places like this will continue to look like this:

Ultimately, homeowners in these places have been sold a bill of goods: "You can buy a house now in a safe, quiet, growing community that will appreciate over time." And the community may grow in population—I expect it will—but it's spread out so thin on the landscape that it's hard to see it ever becoming a sustainable, productive place that generates wealth for inhabitants and enough tax base to sustain the extravagant amount of infrastructure that's already been built. This, of course, being infrastructure that federal financing has supported with home mortgage loans for decades.

Life in the exurban fallout zones of the housing crisis is precarious. It may not be terrible, depending on your situation. If you have a stable income, and you're not banking on your cheap house appreciating to give you a nest egg, you might be fine there. But the future of these places is not bright unless they change course. Federal policy must play a role in that.

As of the last couple years, developers have started building again in Gran Paradiso, that zombie subdivision I told you about before. Just great. Sounds like more boom times in sunny Florida!

Until next time, then.

(All photos by the author unless otherwise indicated.)

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.