3 Ways to Make Streets Safer for Pedestrians

This week, we've invited Strong Towns members to respond to a series of questions on Nassim Taleb's book, Antifragile. You should really read the book (it's a big inspiration for Strong Towns thinking), but if you haven't, you'll still find it easy to jump in on these topics and conversations, based on the second section of Antifragile.

The following is Strong Towns member, Adam Porr's answer to this question:

More people jaywalking makes it safer for everyone yet a single person jaywalking is dangerous. More kids outside playing makes it safer for all kids to be outside playing but one kid alone is more susceptible to harm. Traffic lanes full of bikes and a culture of biking creates safe conditions but a lone biker on a stroad is putting their life at risk. It’s clear we’ve intervened ourselves to extreme fragility. Now that we’re here, how do we go back?

Crossing the street in Portland (Photo by TMImages PDX)

By most people's standards I wouldn't consider myself nervous, or timid, or prone to panic. It usually takes a lot to rattle me, but I've been in living in Portland, Oregon for three months, and there is something that continues to make me sweat like a Wall Street banker on the eve of the crash. It's not the threat of The Big One, or unaffordable housing prices, or even discovering that I've run out of locally-roasted fair trade organic single origin coffee. It's the simple action of driving my car.

As a lifelong resident of the midwestern United States, I'm used to cruising down pretty much any street without regard for pedestrian activity. In most places where I go, there is none, and in the rare case that a pedestrian ventures into the roadway they either (wisely) wait for a Grand Canyon-size gap in the traffic or walk to a stoplight.

Not so in Portland. On even the busiest streets pedestrians cross on a whim, often not at a crosswalk and sometimes without even making an obvious effort to look for traffic! It's as if people - even kids - think they own the street! Rightfully so, because for all intents and purposes they do own it. Accidents, near misses, and road rage happen, of course, but for the most part, drivers are very aware of pedestrians and politely accommodate their crossing wherever they wish to do so.

As someone whose brain has been trained for decades that streets are for cars only, the persistent presence of pedestrians triggers a sympathetic nervous system response that is stressful to say the least. Still, I love it. Pedestrian activity is an indicator of vibrant neighborhoods and a healthy local economy, and upon my return to Columbus, Ohio in a few months I hope to do whatever I can to duplicate this environment. But how can we bridge the dangerous gap between the current culture and one in which pedestrians feel safe to be in the street and drivers are attentive and courteous enough to allow this to happen? I'd like to discuss three strategies that may help.

1. Encourage Pedestrian Strength in Numbers

As long as pedestrian activity is a rare event, drivers will not expect pedestrians to be in the street and will be less aware of them. The solution? Give pedestrians more reasons to be in the street. Augment natural pedestrian activity by hosting public events such as street fairs, tailgate parties, farmers markets, car shows, medieval battle reenactments, or anything else that will draw a crowd.

Discourage local auto traffic by allowing the event to consume parking that would otherwise be available, or perhaps provide a modest incentive (vendor credit or reduced admission fee) to those who arrive by some other means. Be sure to communicate this to attendees in advance! If possible, plan activities on both sides of the street so that pedestrians will cross back and forth during the event, but do not close the street, and try to avoid interfering with normal traffic control. Schedule events frequently, but not predictably. If drivers anticipate an event, at best it will not make a strong cognitive impact and at worst they will simply avoid the area. Schedule events at times of moderately high traffic to increase the exposure to drivers.

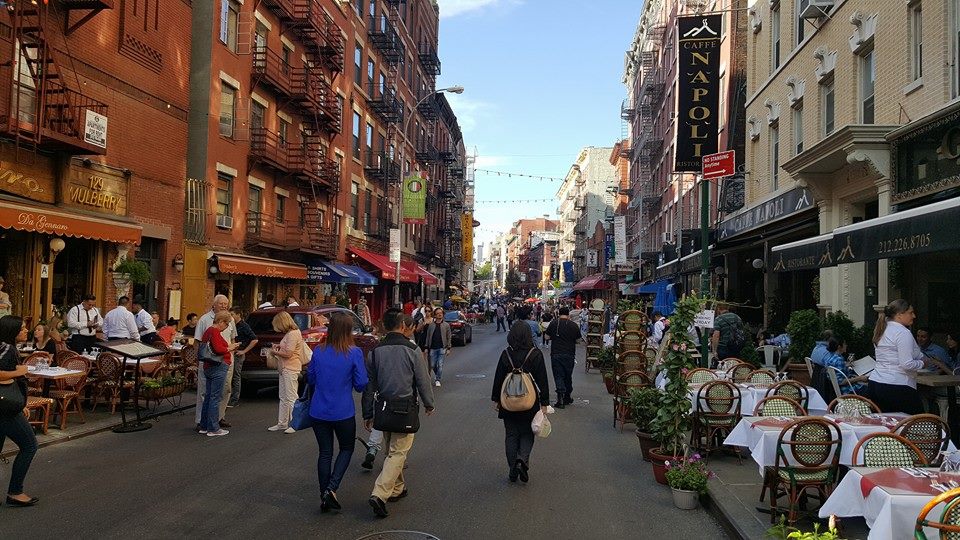

Photo by Andrew Price

2. Force Drivers to Wake Up

Drivers in the areas that I frequent are often distracted, sometimes reckless, and occasionally aggressive, with obvious implications for pedestrians in and near the roadway. They are empowered to do this, in part, because their perception of risk in the environment is low. After all, if you've driven 10,000 miles since you encountered a pedestrian in the street, what are the odds that you'll encounter one on this trip? This risk perception is further enabled by street features such as wide lanes, wide curves, and lack of on-street parking that will accommodate minor driver errors without consequence.

To combat driver complacence, we need to promote built environments that routinely expose drivers to risks with minimal consequences (e.g. scraped fender) in order to encourage behaviors that will prepare them to avoid risks that are rare but more consequential (killed pedestrian). For example, a street with narrow lanes, tight corners, and on-street parking will be perceived to be riskier than a street with wide lanes and a vacant curb or shoulder. Occasional variation in the configuration of the roadway, for example due to intermittent parking, rainwater treatments, or curb bumpouts will also force a driver to stay alert to respond to the changing conditions.

Finally, a busy visual environment near the roadway will force a driver to stay alert to assess each feature and determine whether it is a threat. Buildings with small setbacks create this kind of environment, as do typical sidewalk features such as trees, benches, trash bins, bike racks, signs, and many others. If all of this seems to represent an undue hardship to drivers, keep in mind that it should be pursued and permitted in moderation such that it is only perceived as a high risk to an acclimated driver when the driver is engaging in risky behaviors such as excessive speed. A non-acclimated driver should, of course, perceive the risk to be greater even at posted speeds and adjust their behavior accordingly. It is also important to note that all of these features simultaneously lend themselves to a pedestrian-friendly environment, which will encourage more pedestrian activity.

3. Preserve and Expand Pedestrian Protections

Last and least, there are steps that the authorities can take to mitigate the risk of harm to pedestrians. I saved this for last because, in my experience, these steps are not as effective as the ideas already discussed. These are the obvious steps of reducing speed limits, painting formal crosswalks, signalizing crosswalks, and the like. In visually sparse environments, these signals are likely to be ignored due to the general lack of alertness of drivers resulting from low perceived risk. In visually busy environments, these signals may be lost in the clutter and will therefore be ineffective.

However, even if the signals themselves are not effective at protecting pedestrians, they will likely play two important roles during the transition period from an pedestrian-adverse culture to a pedestrian-friendly culture. The primary role is to empower pedestrians. Even if the signs and crosswalks afford little real protection, they at least acknowledge the right of pedestrians to be in the street. This is an important message for drivers and may provide pedestrians with a sense of legitimacy. The other role of signs and crosswalks is to provide a legal framework to support pedestrians in the event of an accident until the laws are amended to permit jaywalking and provide legal protections to jaywalkers.

Admittedly, it may be difficult to implement these strategies in the most auto-oriented environments, but most of the places that I frequent have at least some opportunity for improvement in these areas. Let's pick the most compelling places and start with those. Perhaps there are more people who, like me, will learn how enjoyable and economically productive pedestrian-friendly environments can be and carry the torch back to their own hometowns!

Read all our antifragile coverage.

Related stories

About the author

Adam Porr lives in Columbus, Ohio with his family. An avid transportation cyclist, he enjoys running errands and exploring the city by bike and on foot whenever possible. He first learned the value of human-scale cities while living and working for a year in London, England, and this experience left him with a deep love for great urban places. Over the years this love turned into a calling, and after working as an electrical engineer for more than a decade, Adam is pursuing a new career in urban planning with an emphasis on geospatial analysis. He discovered Strong Towns in 2014 and became a member soon thereafter. He is consistently inspired by the Strong Towns contributors and their enthusiasm, thoughtfulness, and stewardship of the places they love.