How Suburban Poverty Affects Seniors

Traversing an environment built for the automobile in anything other than an automobile stinks. Even if you can overcome the inhospitable nature of that, there are other people who cannot...people like your grandmother.

One of the first topics I ever wrote about was the side-effects of automobile dependency. Today, I'm going to focus specifically on social isolation and how that has a particularly negative impact on seniors living in suburban areas.

The majority of post-World War 2 suburban development has been oriented around the automobile. From the large suburban plots, to the hierarchical street system, to the strip malls and big box stores — they have all been designed with the assumption that everyone drives. When we create an environment around the automobile, where retail, jobs, and homes are segregated by vast automobile-scale distances, where streets are windy and/or disconnected, often forcing us to take the longest route between two points:

(Photo by FutureAtlas.com)

...it becomes an extremely spread out and automobile-dependent environment. Of course, nobody walks. And because nobody walks, there is no real incentive for developers to build sidewalks.

We have systematically built in this pattern for half a century now, creating an entire country (excluding some of our strong urban cores and historical neighborhoods) of automobile dependency. It is no wonder that we view the ability to drive as being a right, because in an environment built around the automobile, we see cars as symbols of freedom; we are dependent on them for mobility.

This may not seem like much of a problem if you are able to drive - you are of legal driving age, you are able to afford the average $9,000 per year cost to own an automobile, and you have no disabilities. Teenagers, seeking their own independence view getting a license as a right of passage. It is the only way they can make it to their job, to the movie theater, or the mall without being scooted around by their parents. As such, the United States has one of the lowest minimum driving ages in the world.

Often, we do not think twice about the lack of mobility that our children have. If they are 14 years old or younger, we do not care that much that we have to drive them around, because eventually they will grow out of it, and will be able to drive themselves. The perception that cars equal freedom may slowly be fading. Fewer teenagers today are interested in getting their license than a generation ago, despite being physically able to.

But what about Seniors?

Many of the elderly cannot (or should not) drive. Unlike children, it is not a phase that they will eventually grow out of. Are we to throw them into a retirement home, just because they are no longer able to drive and maintain their independence? Should we keep forcing them to drive, when we know that in their advanced age, their vision, judgement, and alertness is not what it use to be? Should we impose the burden of carting them around to their children? In my opinion, all of those are cruel and humiliating options, yet they remain our only options, as long as we keep prioritizing the automobile in the way we design and build our environments.

One of my grandmothers is in her mid 80s, and she lives in a modern duplex, but in a pre-war suburb. There is a park across the street and a bus stop in front of her house that shows up every 15 minutes on weekdays. She no longer drives, but the bus drops her right off in the heart of the city, where she can do her grocery shopping, visit her doctor, go to the bank, and virtually anything else she feels up to. She plays bingo twice a week, and used to meet me every second Wednesday for lunch. She has maintained her freedom despite no longer driving, and I do not think that she would want it any other way.

It would break my heart if someone told her: "You can no longer drive so we are moving you into a retirement facility where a shuttle bus will take you to the supermarket once a week to get your groceries." My grandmother is a cheerful, active lady for her age, and that would bore her to death (literally). Yet, it is the depressing fate of many of our seniors.

My grandmother on the other side of my family faced this fate. She lived in a 1960s-era suburb. Getting to the nearest bus stop required navigating windy, disconnected streets that eventually led to a highway, with a bus stop a few blocks up with 30 minutes frequency. It was an unpleasant commute for anyone, let alone an elderly lady with a hip replacement. She spent most of her time at home, dependent on her children and in-laws just to take her grocery shopping. She became very depressed, was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer's, and was moved into a retirement facility where she passed away a year later.

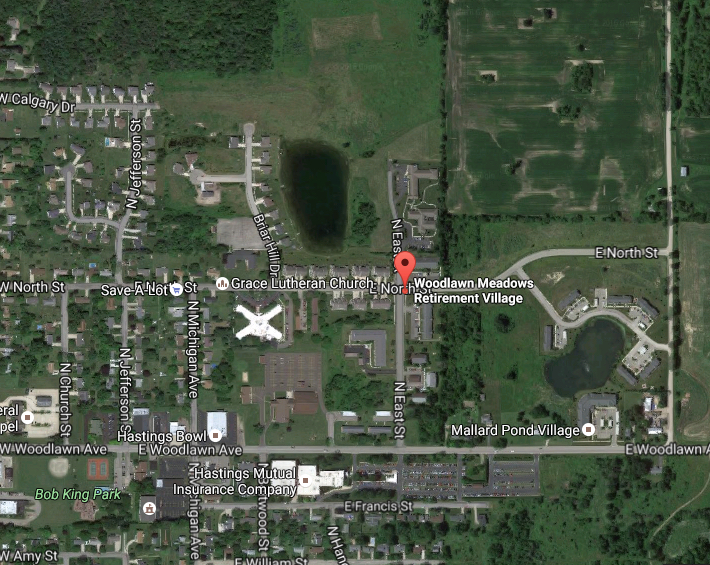

When we plan our communities, we rarely accommodate, or even think about the elderly. We often build "retirement villages" in an attempt to solve a problem that should not exist in the first place, and while these retirement villages are walkable and accommodating inside:

(Photo by Averyhealthcare)

...they are often built right in the middle of automobile-dependent suburbia, isolating those inside from the greater community:

Claiming that residents have the freedom to come and leave whenever they want clearly indicates that either they did not expect many of their residents to survive past driving age, or that they consider a scheduled shuttle bus once a week to the grocery store as 'freedom.'

The Problem of Suburban Poverty

I've already described the challenges of suburban life for any elderly person who can't drive, but let's talk specifically about those challenges for an elderly person in poverty. Because so many seniors are on fixed incomes, any increase in cost of living—whether that's rising rent or property taxes, food, gas or healthcare—could push them into poverty. According to the National Council on Aging, "Over 25 million Americans aged 60+ are economically insecure—living at or below 250% of the federal poverty level." Furthermore, NCOA reports: "Approximately 3.5 million older homeowners are underwater on their loans and have no home equity."

The typical challenges of aging—loss of physical mobility, disconnection from community, health problems—can be compounded in a situation of suburban poverty. The responsibilities of maintaining a large suburban home in an auto-dependent neighborhood present a burden for seniors, especially those who find themselves with a loss of income or increase in costs.

There is a fundamental change that needs to take place in the way we build our towns and cities in order to give our elderly (and the rest of the driverless population—including children, the disabled, and visitors) their freedom.

Is transit the solution?

The problem is not solved by simply adding a bus that comes by every 30 minutes. Especially in a suburban town where the bus drops you off at the parking lot of a single strip mall; you may want to visit one or two stores, but then you will need to stand along a highway for another 30 minutes waiting for the bus to pick you up again. It is not a very pleasant or safe experience.

“There is a gross inequity behind this model; those that can drive are entitled to a productive day, while those who cannot, are not.”

Retrofitting transit on top of an environment designed to be driven from place-to-place results in catching a bus from place-to-place. It is neither a very pleasant or productive way to use your time if you expect to visit the bank, post office, head out for lunch, and get your hair cut all on the same day at different locations, with a 30 minute bus wait in between each. There is a gross inequity behind this model; those that can drive are entitled to a productive day, while those who cannot, are not.

I think that is one of the main reasons transit has such a bad reputation in the U.S. and why cars are viewed as freedom. To make transit pleasurable, we need a strong urban destination that we can take transit to. You may have to wait 30 minutes for the bus to head into town, but you should only have to do that once, because once you reach your destination you can have an enjoyable day out. You can accomplish all your errands and appointments without being late for anything. Transit is part of the answer, but I would argue that we need to focus on strong urban cores to even make transit useful, or we are simply wasting public resources on a service that nobody is going to use.

Even without transit, or if you live in a rural area, if you had a strong centralized urban core, you could take your elderly relative into town every Friday on your way to work, knowing that they would be able to do their grocery shopping, make their appointments, meet you for lunch, and perhaps they can see a movie and enjoy a coffee while you finish the afternoon at work. They would appreciate having their freedom back one day a week out of the house, without inconveniencing the family.

At Strong Towns, we have something we call the "Strong Towns Strength Test," which is a way to determine how strong your community is. One of the key questions that we invite people to ask about their community is: "Are there neighborhoods where three generations of a family could reasonably find a place to live, all within walking distance of each other?" Think about that. Next time you go to label a community as being 'family oriented' - do not just think about the parents or the recently retired that are able to depend on an automobile at a moment's notice. Ask yourself, would your 13 year old kid or elderly granny on a walker have their freedom, and be happy there? For many suburbs, the answer is sadly "no."

There is a reason I am a passionate urbanist. It is not because I like skyscrapers or crowds, but because I appreciate freedom.

A different version of this essay was originally published in 2013.

(Top photo by Sage Ross)

The U.S. senior housing market is poised to shift from a surplus to a shortage in the next five years. In this episode, Abby and Norm Van Eeden Petersman, Strong Towns’ director of Movement Building, discuss the implications of this shift and how to give more options to seniors. (Transcript included.)