A Suburban Poverty Boomtown: Lehigh Acres, Florida

This post is an in-depth look at a high-poverty, declining suburban city: Lehigh Acres, Florida. It is a follow-up to the post "Suburban Poverty: Hiding in Plain Sight", first published on Strong Towns in February 2016.

This week, we've been spotlighting suburban poverty here at Strong Towns. The growth of this phenomenon across our country—more poor Americans now live in suburbs than in central cities—is one of the big, important demographic stories of the last couple decades. Understanding suburban poverty is of vital importance to regional planning and policy.

But the label itself is misleading. It hides the fact that there are many different types of suburbs, and that poverty in nominal "suburbs" has many different causes and manifestations.

Camden, NJ. Source: Wikipedia

East St. Louis, Illinois; Gary, Indiana; and Camden, New Jersey are technically suburbs. But all three are quite urban in form and heavily industrial. Their infamously high poverty and crime rates are a decades-old story, rooted in the same forces that depopulated and impoverished "inner city" areas across the continent: white flight and heavily-subsidized suburban expansion in the postwar era, leaving behind a poor, ethnic minority population beset by heavy job losses in the deindustrialization wave of the 1970s. These places have little to do with the popular conception of suburbia.

Ferguson, Missouri is closer to a classic suburb. Its early inhabitants were mostly white and middle-class. It was built to be a bedroom community for St. Louis. Over time, the housing stock aged and deteriorated, and the community became less attractive and desirable to young families with money seeking a starter home in a good school district.

A gradual demographic transition, not a population boom or bust, has transformed Ferguson into a largely low-income, ethnic minority area that is now best-known nationally for its police department's fraught and exploitative relationship with the black community. This relationship was exacerbated by its fiscal insolvency and reliance on fines and court fees to fund local government operations.

America is full of Fergusons and Fergusons-in-waiting. Inner ring suburbs like it fit the most common narrative of suburban poverty: once-high-end residential communities facing an aging housing stock combined with proximity to poor urban areas.

But in the boom-and-bust Sunbelt states, there is a totally different sort of poor suburb: vast suburban and exurban communities that have boomed in population in response to the spillover demand for affordable housing from more prosperous cities nearby. These places were never rich. They didn't gradually decline. They grew up—explosively fast in many cases, fueled by the pre-Great-Recession glut of subprime mortgages—as poor suburbs, and they will likely die as poor suburbs.

These places were an unfamiliar species to me growing up in the Midwest. You find them in the states that went all-in on the late-20th-century suburban growth model: Florida, Arizona, Nevada, and California. (Texas may well be catching up.) They comprise many of the places that show up on a map of areas hardest-hit by foreclosures in the wake of the Great Recession.

These places are a canary in the coal mine for the rest of the country. They are a sneak preview of what it looks like when the Growth Ponzi Scheme unravels, and of who's going to be trapped in the places that unravel the fastest.

Today we're going to take a field trip to one of these suburbs: Lehigh Acres, east of Fort Myers on the Gulf Coast of Florida.

I've lived in Southwest Florida for several years, and I've been able experience the insanity that is this state's unique postwar development history firsthand. In the 1950s and 1960s, Florida developers bought up absolutely colossal swaths of wilderness along both the state's coasts, far from existing population centers, platted and subdivided them into residential lots with almost no thought to future infrastructure or public service needs, and sold the lots to northern investors. In many cases, they paved a full grid of access streets, but provided no water, sewers, schools, parks, any of the above. Just cheap lots.

Most of these places remained largely undeveloped for decades. Then, starting in the 1980s and 1990s, the populations of many of these pre-platted "cities" exploded:

Source: US Census

Lehigh Acres and North Port's populations quintupled from 1990 to 2010. Cape Coral's doubled. Port St. Lucie's tripled. This is insane growth.

This rapid expansion coincides with two big trends. One is a glut of easy credit for home buyers—much of it in the subprime mortgage market—starting in the 1990s and continuing until the Great Recession. The other is increasing housing costs in the more affluent metropolitan areas to which these exurbs are attached, as most of the prime real-estate (in Florida, this generally means near the beach) had reached build-out.

If you want a fuller picture of what the development pattern looks like in these Florida boomburbs, and the problems that come with it, revisit my previous article on the topic from February. For an understanding of Lehigh Acres's history in particular, I recommend Paul Reyes's fantastic essay from Harper's magazine a few years back, titled "Paradise Swamped: The boom and bust of the middle-class dream." I won't try to describe the place in all its sordid detail, simply because it's already been done so much better than I can do it. Damien Cave's 2009 New York Times article about foreclosures in Lehigh Acres is also a good read.

An Astonishing Transformation

The population in Lehigh has not only grown since 1990, its demographic characteristics have changed considerably, both racially:

Source: US Census (1990, 2000, 2010) and American Community Survey (2014)

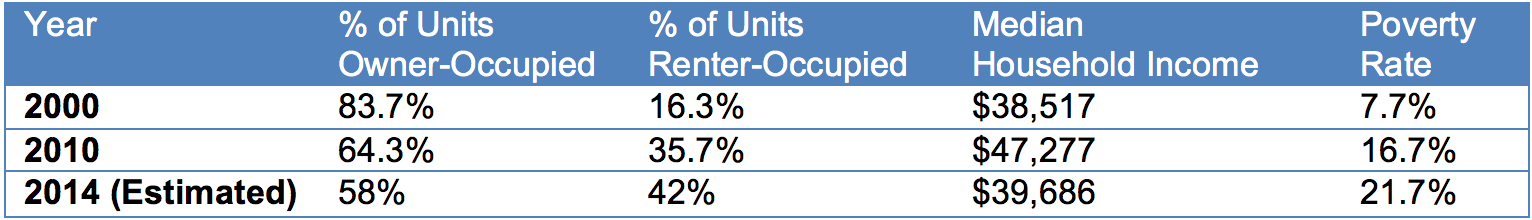

and socioeconomically:

Source: US Census (2000 and 2010) and American Community Survey (2014)

Note the dramatic drop in household income from 2010 to 2014, and the increase in poverty. In 2014, an estimated 30.7% of children under age 18 in Lehigh Acres were living in poverty.

Note also the dramatic shift from homeowners to renters in a period which includes the 2007-2008 subprime mortgage crisis. Who's buying up all those houses that are now rented out? Investors, mostly. And banks still own many of the homes that were foreclosed upon in the wake of the subprime mortgage crash.

Yasha Levine has written, in sometimes-colorful, not-safe-for-work language, about the emergence of Victorville, California as a "post-apocalyptic suburban ghetto" in the Mojave desert. Those displaced from the increasingly-unaffordable Los Angeles suburbs by foreclosure, eviction, or rising rents relocated there, the only place they could manage to go which was still (if barely) commuting distance from the LA and Inland Empire areas.

The post-industrial economy's most disposable people, shunted off to its most disposable places. Is this what's going on in Lehigh Acres? Fort Myers is not the supercharged housing market that Los Angeles is, and doesn't command the same kind of prices—but prevailing wages are also much lower in Florida than in California. The same dynamic may apply: desirable real estate nearer to the coast—that which has a built-in locational advantage—is increasingly out of reach to the working class and poor. They're unwanted and displaced.

I went to drive around Lehigh (there's no other way to get around) to see it for myself.

A Tour of Lehigh Acres

Lehigh Acres's poverty is not uniformly distributed over its vast expanse. The New York Times has a nice interactive map of poverty rates by census tract. I followed this to zero in on Tract 040122, an area in between State Route 82 and Leonard Boulevard with a poverty rate of 49.8%. This is an area of concentrated poverty by any definition, comparable to some of the poorest inner-city neighborhoods in major U.S. cities. (For example, much of the South Side of Chicago, according to the same New York Times map, has census-tract poverty rates in the same high-40% range.)

Source: New York Times

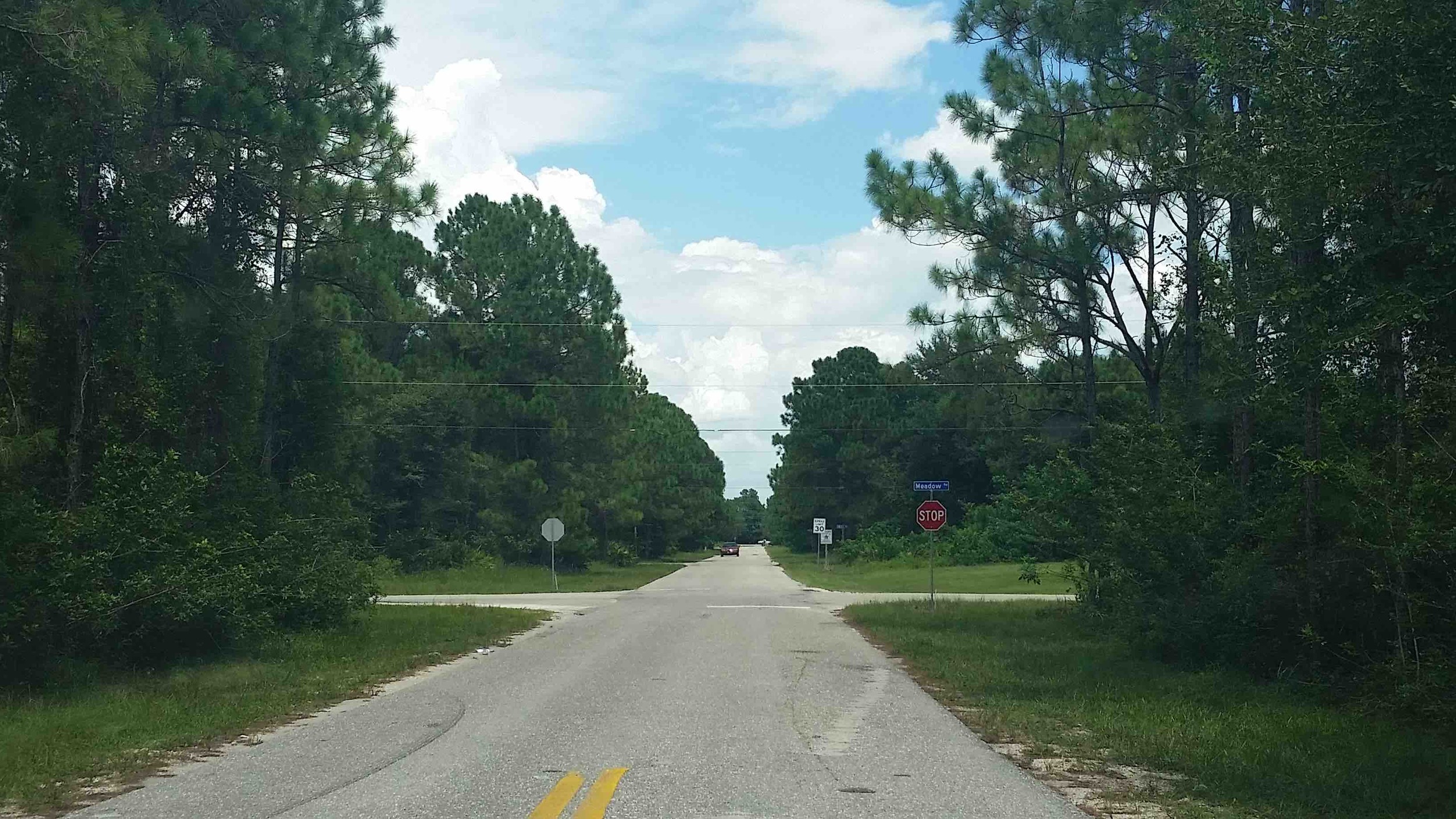

The first thing you notice on the way into Lehigh from Interstate 75 is the feeling of remoteness.

This highway could be anywhere, except that on the other side of that wall of trees on the left, the land has been subdivided into a monotonous grid for miles and miles and miles.

It's very hard to convey the sheer scale of this place, the seeming endlessness of it. Photos don't do it justice.

The architecture, with few exceptions, is incredibly drab.

This isn't surprising. One of the distinguishing characteristics of places that are part of the Suburban Experiment is they're not designed and built to retain value. Materials are cheap. The architecture, urban design and landscaping are frequently banal. Their only appeal is their new-ness, and they're built with little concern for what happens to this appeal 20 or 30 years down the road.

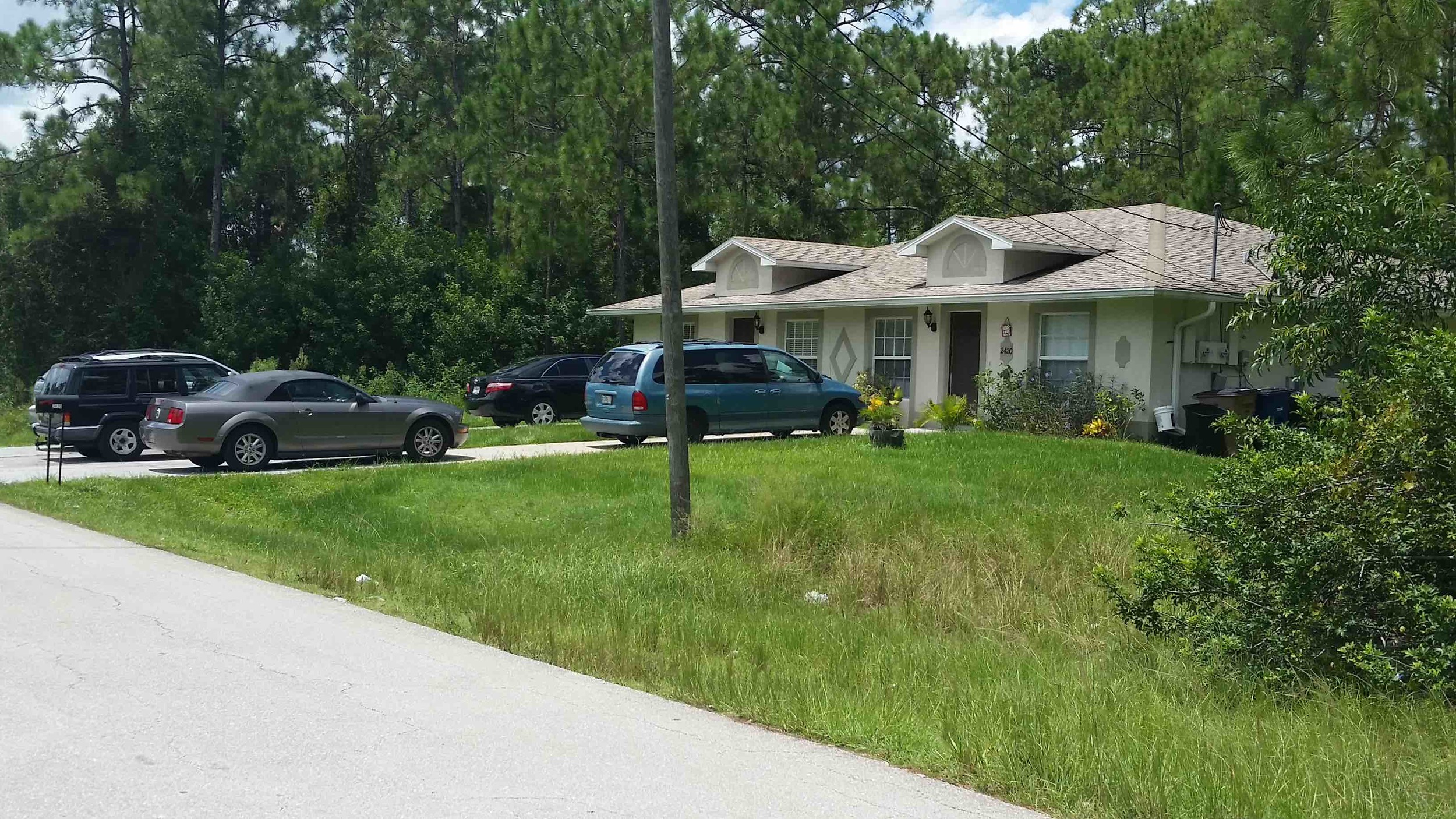

Count the cars!

One of the predominant impressions you get very quickly is that there are a lot of cars per household. Often 2 or 3. For a low-income area, this must represent a tremendous cost burden, and yet, what choice do you have in a place like this? Transit service is so infrequently and spread-out as to be practically useless. If you have to get to a job, you drive.

I did catch a glimpse of Good Wheels, a paratransit service for the elderly and disabled, but if it's anything like what I know of these services elsewhere, it's hardly a comprehensive solution.

Also, there seemed to be a LOT of people home at 1 pm on a Tuesday, judging from the number of cars in driveways and people out and about. Some combination of unemployment and non-9-to-5 hours, I inferred.

A lot of contractors seem to live here: it's common to see vehicles with a company logo. This is where the working class that can't afford coastal Florida's boom-time housing prices gets pushed. They commute west to the coast to serve the McMansion (and real mansion) owners.

A surprising number of people were out walking. I saw a lot of teenagers in groups around 2 pm—presumably just after a high school had let out.

Unfortunately, Lehigh Acres is an absolutely despotic environment to walk in. Not a sidewalk or shoulder to be found. Virtually no shade from the 90 degree heat. And it's August—torrential afternoon downpours are an almost daily occurrence.

Some houses are well cared-for. A lot aren't. The poorest census tract I mentioned above was largely characterized by duplexes. As soon as I drove beyond that area, almost all of the houses were single-family.

There are hardships here that you don't find in the city. The big one is utter reliance on a car as one's lifeline—an expensive and precarious way to exist. There are also issues with deficient infrastructure and the general lack of water and sewer service. (Most Lehigh homes are on well water and septic systems.) But there isn't rampant crime and gang violence. I can imagine choosing Lehigh over a troubled inner-city neighborhood if that's your price range.

The wastelands of Lehigh Acres invite comparison with the hollowed-out neighborhoods of Detroit and St. Louis. The visual similarity can be striking.

They are not, of course, the same thing. Detroit has lost 2/3 of its peak population. Lehigh Acres, on the other hand, has empty expanses because they never filled out, not because they've been depopulated. Lehigh Acres's population is still booming. It's a growing place, but it's not a successful place. It has almost no chance of becoming fiscally productive, environmentally sustainable, or a prosperous community full of upwardly mobile individuals and families. It risks becoming, instead, an increasingly isolating place full of people who are cut off from the economic mainstream.

There's a sort of inexorable economic logic to it: capitalism is always going to leave the most disadvantaged people trapped in the places least valued by the real-estate market. For a few decades of white flight and deindustrialization, those places were overwhelmingly in the "inner city." Now the geography of advantage and disadvantage is shifting. The story is becoming more complicated.

A Note on Unsustainability

It's important to understand that its poorly-planned built form or fiscal unsustainability alone is NOT the reason for this place's decline. Urbanists like to pontificate, sometimes almost gleefully, about the inevitable failure of the sprawling suburbs as they're revealed for the black money holes they've always been. There's a certain lazy schadenfreude that's easy to indulge, and I am not trying to write that kind of story here.

I would argue that predictions of the Suburban Ponzi Scheme's imminent collapse have been greatly overstated. Those with means are going to continue to pile on debt to build the same fundamentally non-viable places for as long as they possibly can. Those without means are going to pay much of the price. What we'll see in the near term is a bifurcation of suburban outcomes—like my fellow Strong Towns contributor Johnny Sanphillippo says, "there are winning and losing suburbs as more prosperous people migrate to better zip codes."

Let me make this point with a local example: directly across State Highway 82 from Lehigh Acres, I found this:

Here we have a gated subdivision under construction. The names associated with these places are always—like "Hampton"—chosen to connote wealth. (Interestingly, they also connote old-world urbanity - the brick street leading into this development is called "Essex Square.") But here's the collector road off of which one turns onto Essex Square.

This place is as un-urban and unsustainable as anything in Lehigh Acres. All of its residents will be car-dependent. It will almost certainly, like countless subdivisions around it, fail to generate enough tax base to pay for its infrastructure. But, while it's new and shiny, its inhabitants will love it. Just up the highway, perhaps some of them will shop at "The Forum," complete with elaborate fountains flanking the entrance:

The superficial trappings of wealth and status will be as ridiculous as ever, and there will be no spatial logic to any of it, no prudent and efficient use of land, no need for this place to exist in the utterly generic location it does, except that it can and someone can make money building it and selling it.

The gravy train will keep rolling for those who can afford a ticket on board. For their gardeners, roofers, janitors, nannies, waiters and sales clerks, there are the nascent slums of Lehigh Acres.

Exclusion and Displacement

To understand Lehigh Acres from an urban planning perspective, consider its regional context. Here's a Google Maps satellite image of suburban Fort Myers along the Caloosahatchee River, near where it empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

This is prime real estate. It's near the waterfront and some of the country's nicest beaches. It's close to downtown, accessible to established job centers and transportation corridors. What else do we notice about it? It's extremely low-density, and consists almost exclusively of single-family detached homes.

This is not the work of market forces. You think the gardeners, roofers, janitors, nannies of Fort Myers wouldn't like to live closer to the beach if there were more safe, affordable apartment complexes for them to move into? There aren't, and this is by design. Single-family zoning, density caps, minimum lot sizes, minimum setbacks: These are pervasive policy tools expressly intended to exclude the poor from the communities of the middle and upper classes.

This has been true since such residential zoning's 1926 origins in the Cleveland suburb of Euclid, Ohio, upheld in a Supreme Court opinion which included the observation, "In such sections, very often the apartment house is a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district."

Lehigh Acres exists because Fort Myers created it. Because those of means walled themselves off in subdivisions and said to the service workers who support their lifestyle, "Go find somewhere else to live. Not here."

Victorville, California exists because Los Angeles created the Inland Empire, and when the Inland Empire filled up (because it, too, is almost exclusively low-density subdivisions of single-family detached homes, albeit not upscale ones) it created Victorville to house those further displaced.

Same story, different city.

What Can Lehigh Acres Do?

None of this systemic analysis, of course, helps the people living in Lehigh Acres now, whether they would like to leave or they consider it home and want to stay forever. None of it makes the place less dysfunctional for those households that can't afford multiple cars, or are struggling in other areas because of the cost of driving and maintaining those cars. None of it provides the legions of teenagers walking on the side of the road a safe way home from school. None of it helps the disabled, the elderly, or the recently or chronically unemployed, access the social services they need. None of it helps someone whose mortgage is underwater.

None of it will help any of the property owners in Lehigh Acres when the miles upon endless miles of roads crumble and there's not nearly enough money to repair them. Because there won't be. (Want to shake your head sadly? Check out Lee County's helpful "How Do I Get My Road Paved?" guide for residents. It seems the short answer is "You don't.")

There are, I think, strategies that can help a place like Lehigh Acres—and they're not dissimilar to the ones that have been proposed for the hollowed-out, blighted sections of cities like Detroit. This topic is huge and warrants its own entire post, so I plan to write a follow-up in the future about what we can do with a place like Lehigh Acres, given that it exists and many, many people live there who aren't going to pack up and move.

In the meantime, it's important to shine a light on the destructive fallout of America's radical late-20th-century experiments with automobile-oriented development and zoning as a tool of socioeconomic exclusion. Its outcome, at its most extreme, is Lehigh Acres. A disposable place for post-industrial capitalism's disposable people.

(All photos by Daniel Herriges unless otherwise noted)

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.