Urban Moats: Barriers to Growth in Rome, Utica & Schenectady

Strong Towns member Arian Horbovetz is a photographer and blogger based in Upstate New York. Today we're sharing an article from his blog, The Urban Phoenix, republished with permission.

There are times when we amateur urban planning junkies get a chance to use clear, publicly available data to tell a descriptive story about a community. It’s the “why” something does or doesn’t happen expressed in numbers that anyone can understand that gets me excited. OK, I’m a bit of a dork, but follow me here.

You may know by now, but Syracuse and Rochester are joining cities all over the country in removing parts of their downtown expressways. This is due in large part to the fact that they have outlived their structural lives (expressways take an enormous amount of money to maintain), but there is another reason that is behind foregoing any further upgrades… it’s the simple fact that highways that move large amounts of traffic through a city at high speeds actually detract from the socioeconomic prosperity of that city.

The concept is simple: the faster you move through a city, the more elevated you are above a city, the less you see of that city. You don’t see that new store that opened or the restaurant on the corner. You’re traveling at 55mph, you need to focus on the road in front of you!

If you’re a pedestrian on the ground, you’ll have to find a seedy underpass to get beyond the expressway, which is loud, dirty and unappealing to just about everyone. Expressways act as moats, dividers in the city’s they serve, creating an unfriendly walking city environment wherever they may be.

And it’s not just highways. Studies show consistently that high speed, high volume traffic counts on regular roads can have a harsh effect on growth in that area. Today, I'm going to share three examples that clearly illustrate how this concept impacts small New York cities.

ROME

The map of downtown Rome, NY below is overlaid with traffic counts. Very simply, the numbers along each road represent the daily traffic count for that road or street. Note that most of the downtown streets have daily traffic counts in the 1000-7000 range, which is very conducive to a pleasant, walkable environment. Anyone who has walked Rome like I have knows that a stroll down James Street or West Dominick is pleasant, calm and relatively quiet. One can feel safe crossing either of these streets, and in general, there’s a feel of small town comfort as traffic trickles by at about 30mph.

But Rome has a silent demon that more than likely plays a role in choking the city, and that’s the orange and red lines of 19,000-27,000 traffic counts as seen below.

Look how Black River Boulevard and Erie Boulevard create a wall of traffic so to speak… this wall is both physical and psychological, something I will explain a bit later. If you are in Rome, you can (I’m painting with a very broad brush of course) feel the difference from one side to another. North of this interchange we find a lovely downtown and very nice homes. On the other side, the homes are much smaller and more run down. There is less “action” on the street. There are so many wonderful shops and restaurants along East Dominick Street, but likely these places will never be allowed to reach their full potential with a five lane highway cutting them off from the rest of the city.

Let’s use Google Street View to show you a real world example. In the two photos below, Black River Boulevard is the picture on the left. On the right is James Street. When looking at these pictures, don’t just use your eyes… imagine the noise of the cars, or the wind in the trees. Imagine the smell of fumes versus the scent of the air. Which would you rather walk alongside? Which would you rather cross?

Many Rome residents have told me that Fort Stanwix is the beast that separates their city, but I believe the divide would be there even if the fort wasn’t. The street level highway that bisects the city is likely the real barrier here. The full potential of all that Rome has to offer may never be fully realized until traffic calming initiatives and better pedestrian and cycling access is implemented on and along Black River Blvd. and Erie Blvd.

UTICA

Genesee Street in nearby Utica has a bustling feel to it, as the city’s main stripe through downtown is starting to thrive again. As seen below, traffic counts between 6000-8000 make it a relatively pleasant jaunt for pedestrians looking for a store, a service provider or a great place to eat. That is, until you move north and have to cross Oriskany Boulevard and it’s 20,000 car traffic count… oh and those cars are moving upwards of 40mph. Oriskany is shown below in orange.

Recently I blogged about the future of Utica’s Bagg’s Square, and the crucial need for a “street diet” (lane or lane width reduction, traffic calming features, etc.) and better pedestrian infrastructure to make crossing Oriskany more attractive to those on foot. There are a great number of development plans in the works, but the area between Oriskany and the railroad tracks will likely continue to struggle unless the aforementioned steps are taken. Utica Coffee, The Tailor & The Cook and Utica Bread are among the exceptions to this, as they reside along the very pedestrian friendly, slow traffic feeder street that parallels Genesee.

Thankfully, there are major plans in place to make the necessary changes to Oriskany mentioned above. This should open the gates to areas like Bagg’s Square that are ripe for development and ready to thrive again.

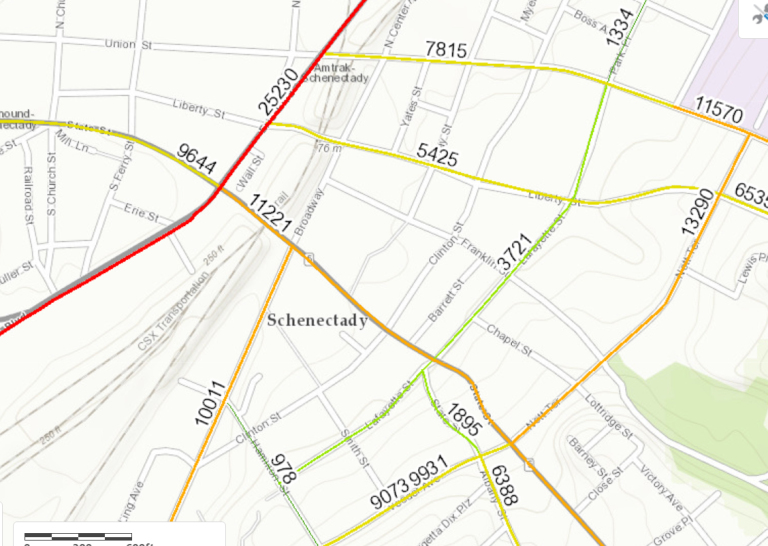

SCHENECTADY

One of my favorite small cities in Upstate, New York is Schenectady. This Capital Region community has taken a phenomenal approach to downtown development, boasting a thriving urban center with retail, restaurants, nightlife and entertainment.

The glaring red stripe of 25,000+ daily traffic count that is Schenectady’s Erie Boulevard divides State Street in two. The southeast side is thriving, while the northwest side seems to be slow to develop. The northwest side has some fantastic street-hugging real estate that looks ripe for development, but is currently filled with an abundance of empty storefronts. Could it be that Erie is acting as a barrier, shielding this section of the city from Schenectady’s walkable downtown?

To be fair, the section of Erie Boulevard that extends south of State Street has undergone a tremendous transformation, complete with traffic calming and pedestrian amenities that slow traffic and make it more attractive to walkers. The hope is that this will have a positive effect on an area of the downtown area that seems to be a bit slower to develop.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF “TRAFFIC MOATS”

To understand the psychological impact of high speed roads, walk for 5 minutes along a busy, 4-lane, 40mph+ road with constant traffic. Don’t wear headphones, just try to be aware of how you feel when cars go by or when a truck spews exhaust in the air in front of you. Be aware of what your mind says to you. Most likely, you will realize that this simply isn’t a very fun place to walk.

Now take a 5 minute stroll along the sidewalk of a narrow, 25-30mph two lane street lined with trees and parallel parked cars. Notice how much safer you feel, how much quieter it is to walk, how much more enjoyable the experience is.

The two above examples may be painfully obvious, but remember that our brains make these distinctions between comfortable and uncomfortable context automatically. Without us knowing, there are often unconscious reasons we choose one restaurant over another, why we walk or drive down one street or another. Our brain tells us which is the more enjoyable experience and that’s what we are most likely to choose. This is the psychological impact that heavy, high speed traffic has on our brains: it “drives” us away, telling us to stay in a more comfortable walkable environment.

To claim that high traffic counts and lack of pedestrian access alone are the only reasons one area thrives and an adjacent area struggles would be irresponsible. Nothing in the urban design world stands alone, and everything has an impact on everything else. Making changes to the high-traffic pedestrian barriers mentioned above will not fix the problem entirely, rather they will open the gates to continued development and smoother neighborhood transitions in our communities.