Stop Shoehorning Suburbia into Walkable Places

As we revisit some of the best articles from 2017 (see them all here), this essay stood out to me. When it was published in May, it generated a wave of responses from other people who shared Sarah's frustrations and experience with this very issue in their own cities.

At Strong Towns, we are often asked "If suburban development is bad for our communities, what should we do with all of the suburban areas that have already been built?" In truth, there is no easy answer and attempts at turning auto-oriented suburbs into walkable urban neighborhoods are incredibly costly, often falling prey to the same flawed financial models that built the suburbs in the first place. Sarah's essay makes a simple request: At least stop bulldozing good quality historic buildings and streets in order to build yet more suburban-style development. Hold onto these treasures and take small steps to make them better. That's where we have to start if we want to build strong towns. - Rachel Quednau

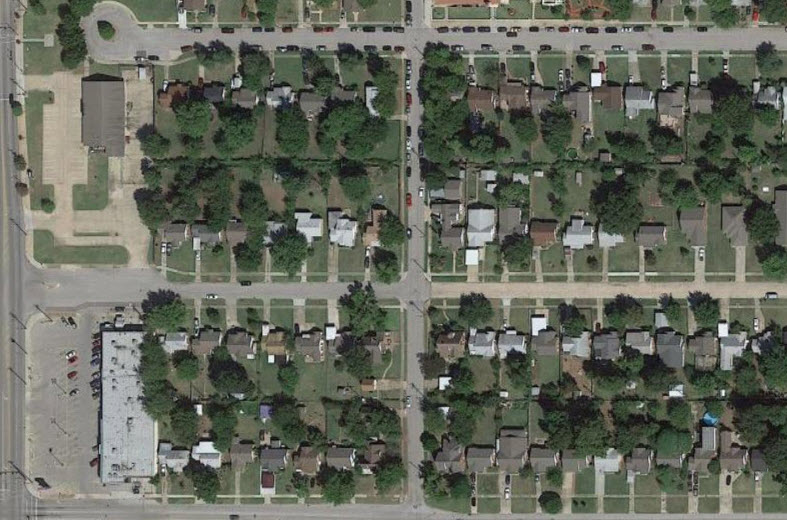

Culs-de-sac, drive-thrus and surface parking lots are NOT what this neighborhood needs. (Photo: Google Maps)

It’s pretty easy to destroy a walkable place. We’ve been doing it for so long, it’s almost second nature. Step 1: Prioritize auto travel. Require every new building to be surrounded by lots of parking and require every new street to be designed for high-volume, fast-moving traffic. Step 2: Designate separate areas for people to live, work and shop, and don’t allow any of these “uses” to mingle. Step 3…. Well, actually, the first two will do it.

I could go on. We could talk about over-zealous fire marshals, outdated subdivision regulations that recommend cul-de-sacs instead of connected streets, federal policies that prioritize single-family suburban homes over mixed-use buildings, and inadequate transit systems. We could certainly talk about redlined neighborhoods, the Interstate Highway Act, and urban “renewal”—policies that transformed American cities like the Allied bombers transformed Dresden.

But let’s keep it simple. Over decades—one parcel and one building at a time—we have created new places where it’s virtually impossible to survive without a car, while systematically chipping away at the older places that used to be fully functioning, walkable, high-yield neighborhoods. Little by little, these once thriving areas have been degraded until they no longer work for people on foot.

OK, so mistakes were made, as the politicians like to say.

I can almost forgive the mistakes of the past. (Well, not all of them. The more I learn about the history of federal housing policy, the more it makes my head explode. I also retroactively hate everyone responsible for demolishing architectural treasures because someone wanted more parking or a building made of precast concrete. For the perpetrators of these crimes, I’m going to hold a grudge.)

But I really do believe that most people had good intentions and acted in good faith. I’m sure that for the past 70 years, most civil engineers, city planners and members of local planning commissions thought they were doing the right thing to make their cities better. All that “shiny and new” stuff probably looked pretty good at the time.

In hindsight, maybe this wasn't such a great idea... (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

Fine. We’ll add the suburban development pattern to the long list of humanity’s mistakes that occurred during the latter half of the 20th century. Like feathered bangs, the Ford Pinto, or any tattoo you got before the age of 35, sometimes we err—not because of malice—but from an understandable combination of ignorance and exuberance.

The thing that really drives me crazy, though, is the present. Now, we know better. We recognize the economic, human health, and environmental benefits of traditional building patterns. And yet, there is so much inertia built into the system that we just keep building car-centric crap like it was 1985.

Here’s the conundrum: it’s incredibly hard to insert walkable places into an auto-centric landscape. In areas defined by fast cars, wide streets, large lots, single-use zoning, and inhospitable asphalt blast furnaces, you can’t just build a nice storefront up by the sidewalk and expect it to succeed. Your otherwise perfect design will fail as a walkable place because of everything that surrounds it. Good luck trying to grow a fern on a sand dune in the Sahara.

Go ahead, I dare you. Just try to build something walk-friendly here. (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

But you can all too easily insert a car-centric development into a walkable area with no negative consequences (to you). Your single-use, suburban-style development will function as designed—for people in cars—operating independently from everything around it. Meanwhile, that single inappropriate project will degrade everything else in the surrounding ecosystem that makes the place desirable to begin with. It will increase auto traffic while disrupting the urban fabric and acting as a barrier to people on foot.

It's a hard habit to quit.

In older parts of the city, walkable neighborhoods are being rediscovered and revitalized because they’re interesting, human-scaled, and pleasant. People are drawn to them because they have character, and because it’s nice (and free!) to be able to walk to dinner or bike to meet friends for coffee. Understandably, the moment a particular neighborhood becomes popular—thanks to its historic buildings and traditional building pattern—it will attract new development. But if you’re not prepared with zoning laws or citizen activisim to enhance and support walkability, you’ll get what everyone knows how to build, which is crap for cars.

#PedestrianUnfriendly (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

It doesn’t take much to punish a pedestrian.

A blank wall, a surface parking lot, anything with a drive-thru—these all signify to pedestrians that the walkable area has ended. They are evidence that we’ve left the human realm and are now operating in an auto-only area. Our bodies respond accordingly. Like early explorers who’ve come to the end of the known world; we’re immediately uncomfortable and on guard. Most people will stop and turn around. The built environment warns us: Here be dragons.

So I'll be blunt. Attention everyone: Please stop building suburban crap in historic, walkable neighborhoods. Geez! You’ve got the whole rest of the city that’s perfectly designed for that stuff. Quit trying to shoehorn it into old districts where its very presence creates dysfunction for the properties around it.

Unfortunately, this is often what our zoning code requires.

Neighborhoods that were built before the advent of zoning were a mix of residential, commercial and industrial activities. When city planners were later tasked with drawing up zoning maps, they had to pick a single use, so they labeled the existing places where people lived above shops and restaurants as “commercial.”

Whittier Square in Tulsa, OK. (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

Since that time, we have gradually added requirements to our ordinances governing commercial lots: parking per square foot of building space; percent of landscaping area; maximum floor area ratios; building setbacks, prohibitions against residential uses, and many more. But every one of these requirements was created with car-oriented, suburban-style development in mind. The zoning code didn’t support the old places built for people on foot, and in far too many cities, ordinances and zoning maps have still not been updated to protect these incredibly valuable assets.

Two blocks south of historic Whittier Square, Tulsa, OK. (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

We desperately need more high-quality, walkable places, not only because people love them, but because they are revenue producers for our cash-strapped cities. Traditional building patterns utilize land and resources far more productively than car-oriented developments, while generating more tax revenue than they consume in public infrastructure investments.

So, what next?

Sprawl repair is complex and expensive. The challenges of transforming car-oriented suburbia into traditional walkable environments are mind-boggling. In our newest neighborhoods, there are just too many cards stacked against walkability.

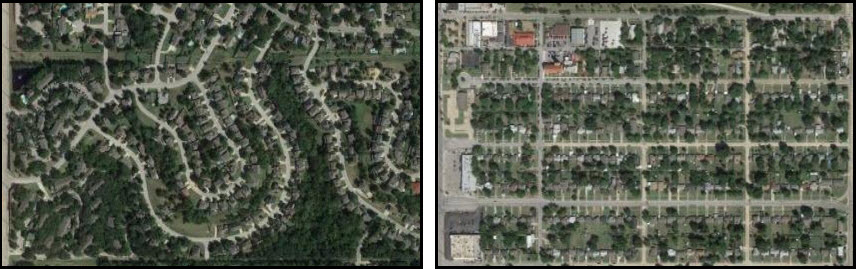

Two different neighborhoods, each with different problems. Which one looks easier to fix? (Photos: Google Maps)

Fortunately, many cities are loaded with older, overlooked neighborhoods with the perfect DNA to support walkability. They have good bones, despite decades of neglect and the intrusion of too many auto-centric developments. If you need a clue, just look for places with compact street grids, houses on small lots, alleys, mixed-use streets with traditional storefronts, historic fourplexes, etc. These are the areas of town with the greatest potential because so much is already right, and small investments can have drastic results.

All we need is the common sense to improve these areas without destroying them.

The Suburban Experiment killed the starter home. Here's how cities can bring it back to life.