The History of Urban Freeways: Who Counts?

To those of us who advocate for healthy, vibrant, human-scale cities, opposing harmful transportation infrastructure projects—the kind that eviscerate all of those qualities in every area they touch—is a bit like battling the walking dead. You think you've killed them but they just won't die, and new ones have a way of popping up, eliciting an exasperated, "Really? Again?!"

“The fact that we’re seriously having this discussion in 2017 is disturbing, given the ignominious and well-documented history of projects exactly like this.”

Such was my reaction to learn about the proposed "Inner-City Connector" in Shreveport, Louisiana, a 3.6-mile long freeway extension which would close a gap in I-49 and make it easier for long-distance motorists to zip through Shreveport without ever seeing the city. Strong Towns member Jennifer Hill laid out the story behind this project and the reasons it's a colossally ill-conceived proposal in an article yesterday.

But the fact that we're seriously having this discussion in 2017 is disturbing, given the ignominious and well-documented history of projects exactly like this. The fact that we're seriously still having this discussion in places like Shreveport is evidence of how disastrously out-of-touch both the priorities of the Louisiana DOT and the Federal Highway Administration, and the planning and funding mechanisms used to produce large infrastructure projects like this, still are.

Some historical context is necessary here. Much of it is probably familiar to Strong Towns readers, but it bears repeating.

A Brief History of Urban Highways

America has a long and shameful history of ramming ill-conceived freeways through—almost always—low-income neighborhoods populated largely by people of color. These projects have invariably destroyed and displaced whole communities, devastated the tax base of cities while subsidizing suburban commuters, and created unseemly "moats" of high-speed traffic and polluted air that ruined the urban fabric of city neighborhoods for a generation or more.

The economic death spirals into blight, abandonment, and rampant crime that were endured by countless inner-city neighborhoods in the second half of the 20th century probably owe as much to freeways as to any other single factor.

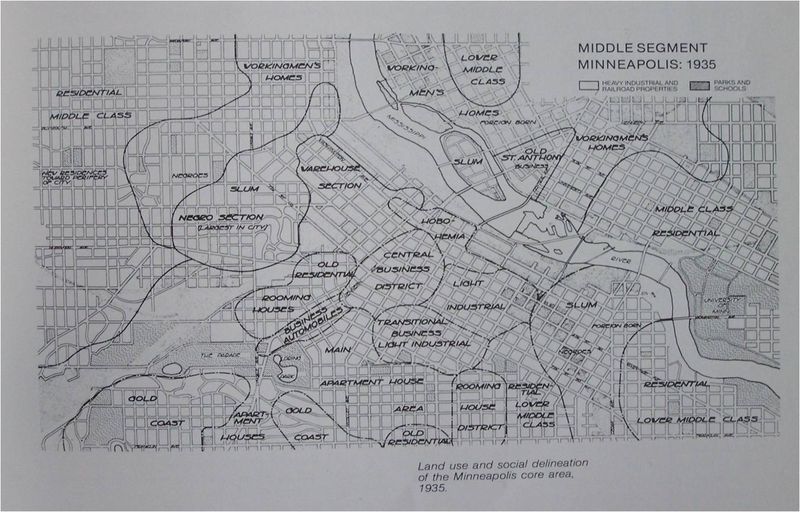

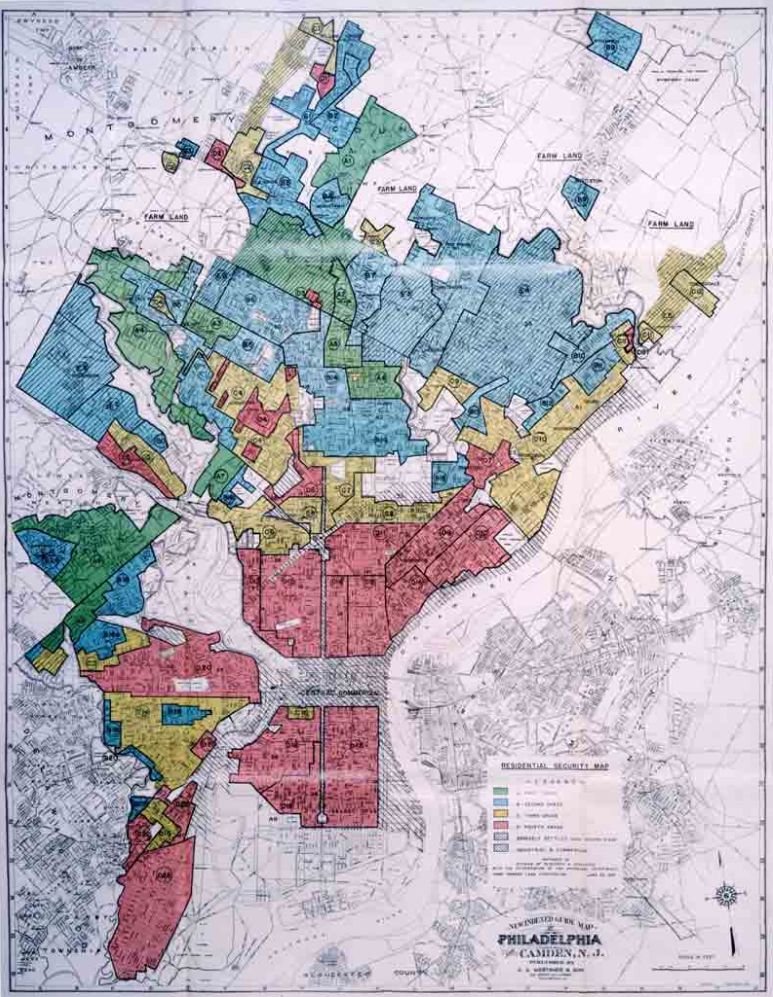

A HOLC (Home Owners' Loan Corporation) redlining map of Philadelphia, adopted by the FHA in the 1930s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

We built the bulk of these inner-city freeways in the 1950s and 1960s, due to a "perfect storm" type confluence of incentives and policy factors. This article from Vox last year lays out the history quite well, complete with photos.

There is little doubt that racism played an enormous role in this, although that's not the whole story (more on that in a minute). Racial discrimination had been an explicit part of federal government policy toward cities since the mid-1930s, when the newly created Federal Housing Administration adopted lending guidelines regarding in which areas it would and would not underwrite home mortgages. These guidelines enshrined in federal policy the practice of redlining, or refusing to lend in neighborhoods seen as risky investments, marked off with literal red lines on some maps. These "hazardous" areas included nearly all neighborhoods occupied by significant numbers of people of color.

Levittown, PA in the 1950s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

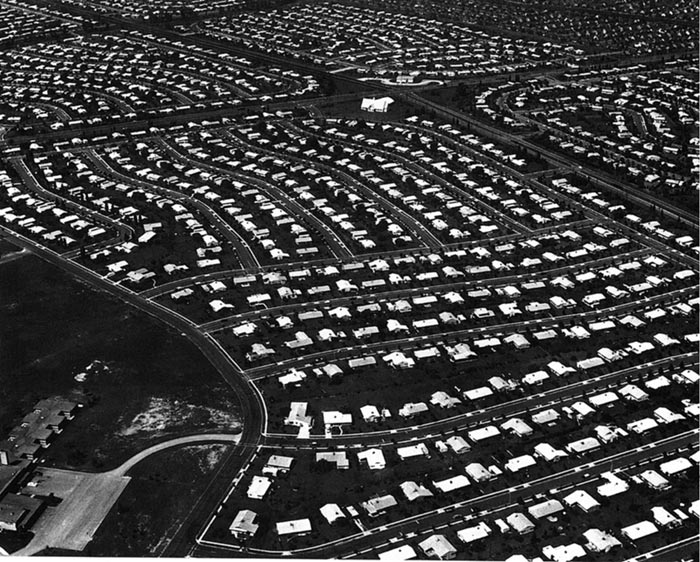

Thus, by the 1950s, majority-minority neighborhoods in cities across America had already been branded as "blighted" or declining. This was more of a self-fulfilling prophecy than neutral description. The government had shut off the spigot of lending to investors who might have incrementally rehabilitated those neighborhoods, while underwriting (and, after World War II, heavily subsidizing through the GI Bill) millions of mortgages for new suburban homes for almost exclusively white families.

The '50s were the decade of urban renewal—expansive, federally-funded schemes to raze areas of urban blight—often areas populated by people of color, and almost always areas adjacent to downtown business districts where the real estate was of great interest to developers and large corporations. Urban renewal projects were driven by the profit motive of these powerful actors, along with the utter disregard of city officials for the people who would be displaced from their homes and neighborhoods.

Those residents simply didn't count. "Blight" was treated as a problem only of dilapidated and undesirable building stock, not one of lack of wealth in these minority communities. The latter could have been addressed by actually investing in building the wealth of those communities.

Into this environment of disregard for the wishes or interests of affected communities came the Interstate Highway System, funded through an unprecedented commitment of federal funds in 1956. Interestingly, President Eisenhower was reportedly surprised to learn that U.S. interstates under construction during his tenure were to penetrate into cities. Eisenhower had seen the German Autobahn, and imagined a system of freeways which would have connected far-flung metro areas to each other, but terminated at ring roads/beltways rather than slicing right into city centers. This is how most European freeways are still laid out today, and one suspects the history of American "inner cities" would have been vastly different if we had had the foresight to do the same.

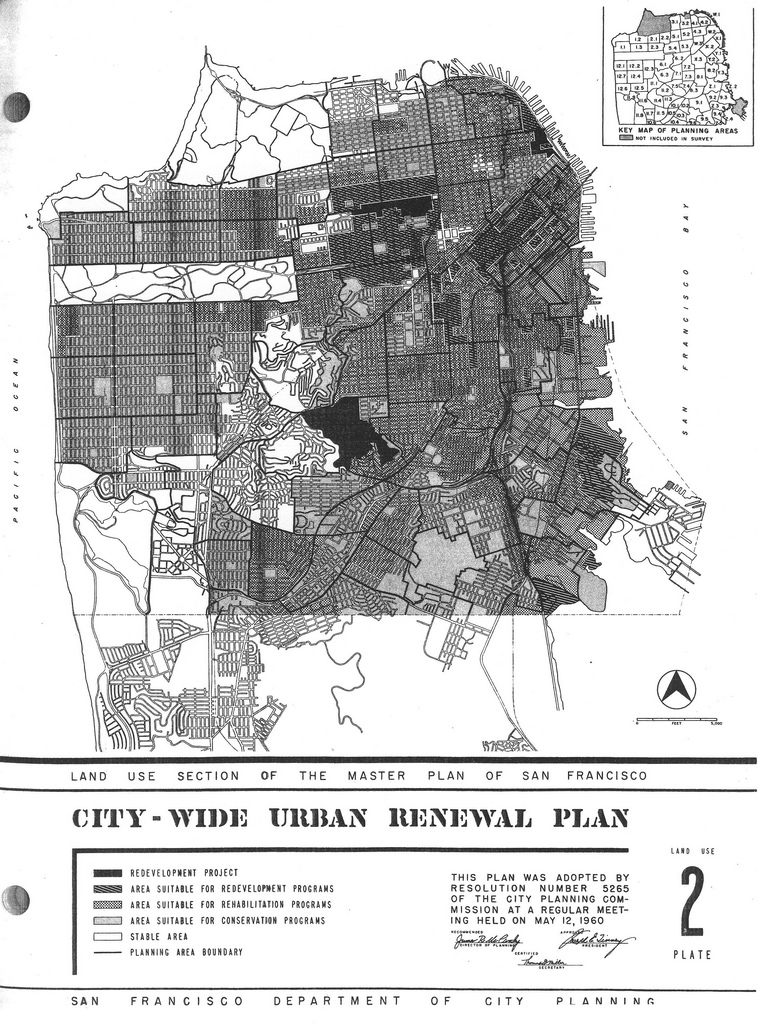

San Francisco Urban Renewal Plan. Source: Eric Fischer via Flickr. Labeled for noncommercial reuse.

There was significant debate during the early years of the Interstate system over whether freeways should in fact penetrate American cities. But key business interests wanted to facilitate the growth of booming commuter suburbs and link them to downtown office districts. And the traffic engineers tasked with designing the interstate system were trained to prioritize the efficient movement of cars from A to B above all else. So in America, city after city after city carved up its core neighborhoods with freeways. Often, federal funding would be withheld unless a resistant city consented to an inner-city freeway alignment.

Freeway overpass under construction, Seattle, 1963. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Almost invariably, these freeways were routed through the very same low-income, minority neighborhoods that FHA redlining maps had deemed "hazardous" two decades earlier. This was a matter of expedience if nothing else: these neighborhoods were the most disenfranchised and the least able to put up effective political resistance to the freeway and the mass condemnations of property necessary for its creation.

The Impact of Inner City Highways in the Twin Cities

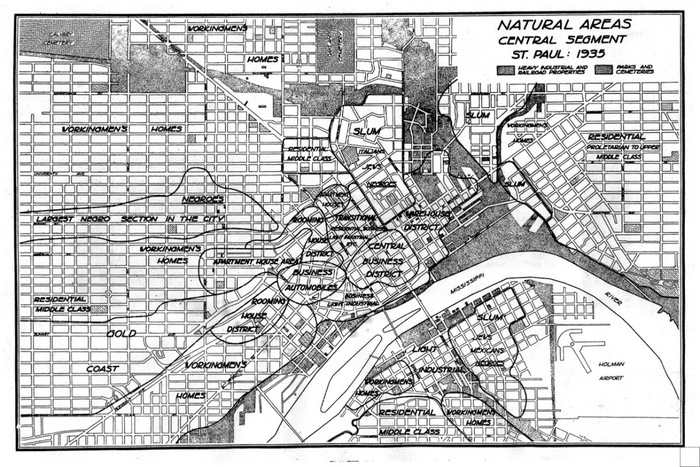

Minneapolis cartographer Geoff Maas has made two striking maps that illustrate the way freeways were systematically routed through poor non-white neighborhoods. They rely on a curious set of 1937 maps created by the Minneapolis Council of Social Agencies to illustrate the demographics of the city at the time. The originals are here—pardon their archaic language which, needless to say, would be impolitic today:

Maas colorized the old maps and overlaid the locations of modern freeways onto them. The result could hardly be a more effective indictment of the racism of 1950s transportation planning. See the fate of the black neighborhoods of Minneapolis:

Click to view larger

and Saint Paul:

The neighborhood destroyed in St. Paul for Interstate 94 with what appears to be surgical precision (see the left middle of the above map) was called Rondo. It was the heart of the city's African-American business and cultural community, and home to a lot of important social capital for that community. The community never really recovered from its destruction.

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Similar stories, similar lost neighborhoods can be found around the country. Black Bottom in Detroit. Brooklyn in Charlotte, NC. Overtown in Miami. The West End in Cincinnati. There are many, many more.

Adding Shreveport to the List?

It's now 2017. Here's a racial dot map of Shreveport, Louisiana, based on the 2010 census. Blue dots represent white residents. Green dots represent African-American residents. I've overlaid a red line indicating where the I-49 connector is proposed.

Source: University of Virginia interactive racial dot map, data from 2010 U.S. Census. Map modified by author.

Ah, how things don't change. Are we really talking about adding Allendale to that list of damaged neighborhoods?

The narrative of institutional racism and callous disregard for minority populations is a true one, and an important part of the story of inner-city freeways in America. But it is not the whole story, and in some ways, it's a narrative that makes it too easy for us to wash our hands of the sins of our predecessors. Every public school child in St. Paul where I grew up learned about Old Rondo, and we all marveled at the shortsightedness, cruelty, and dare I say cartoonish evil of the highway planners of the day. Much the way Jim Crow segregation is taught today, it's framed as a thing less-enlightened people of the past used to do, and thank God we know better now.

“Even without the kind of overt racial animus that was socially acceptable in the 1950s, overtly discriminatory outcomes can persist because of what we measure and what we don’t in evaluating the merits of these projects.”

But do we? What the heck are they thinking in Shreveport, then?

I submit that we haven't come all that far when it comes to the institutional priorities of highway engineers or the mechanisms by which highway projects are evaluated, planned, and funded. Even without the kind of overt racial animus that was socially acceptable in the 1950s, overtly discriminatory outcomes can persist because of what we measure and what we don't in evaluating the merits of these projects.

A look at the economic impact analysis for the various alternatives for the Shreveport project is illuminating. The FHWA, Louisiana DOT and their consultants estimate the economic benefits of an inner-city alignment to exceed those of sticking with the existing beltway alignment for essentially two reasons.

The first is travel time savings. The standard methodology used in studies of travel-time savings is notoriously flawed. It presumes that people value their time in a linear way and that saving small, disconnected increments of time will actually result in more productive activity, a highly questionable (and in fact quite mockable) assertion. See Chuck Marohn's further analysis of this document for more on that.

The economic impact analysis also argues that the inner-city freeway alignment will have greater benefits for real estate development than maintaining the routing around town, and leaving the inner-city route on surface streets. The report claims that the freeway will enhance real-estate development in inner-city Shreveport by providing more highway access to the area. This is exactly contrary to the actual experience of nearly every city that has built an inner-city freeway in the past several decades. But hey. Who's counting?

“This economic impact analysis is designed to reach a completely foregone conclusion, based on an unexamined and disastrous assumption: mobility is good, so more mobility can only be better.”

More damning are all the things that are not addressed at all in this study, because they're indirect effects and/or difficult to quantify with certainty, and project funders like certainty. The economic impact analysis makes no mention at all that I can find of the potential loss of property value for existing real estate near the new freeway, despite that this has been a consistent outcome of urban freeway construction through established neighborhoods nearly everywhere. There is no mention of the economic costs of reduced public health from air pollution, or new public safety challenges that might result. There is no accounting for how the loss of within-neighborhood connectivity because of a new freeway "moat" might depress economic activity.

This economic impact analysis is designed to reach a completely foregone conclusion, based on an unexamined and disastrous assumption: mobility is good, so more mobility can only be better.

The only problem this project seeks to solve is, "How do we move more vehicles through Shreveport?" And thus, that's the only problem it will solve. There is no room for the concerns of low-income Shreveport residents in this analysis as it's been conducted.

Who counts? Who isn't counted? This is how institutional racism and classism perpetuate themselves in the absence of obvious-bad-guy racists or classists.

Shreveport, Louisiana. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The good news is that the Inner-City Connector is still a long-shot project. The opposition to it is growing, and can hold up the example of the disastrous consequences of past projects like it in other cities, something that freeway opponents in the '50s and '60s didn't yet have to show.

The bad news is that a proposal like this even saw the light of day in 2017. It shouldn't have. That it did can only be read as a harsh indictment of the messed-up priorities that are still prevalent in state DOTs and in the transportation planning profession.

Even in the '50s, with lack of hindsight, freeways slicing through inner-city neighborhoods were only rational through the lens of a single-minded focus on moving cars from A to B. Fast forward, and we got exactly what we designed for: the evisceration of once-productive urban neighborhoods. As Rochester, NY City Engineer James McIntosh recently joked to CNU, “We built an evacuation route. It worked. Everybody evacuated.” If we do the same thing in 2017, we're going to get the same results.

High speed freeways are never the route to a vibrant city. But vibrant cities are clearly not high on the priority list of federal and state transportation planners, and so it should fall to the leadership of cities like Shreveport, as well as activists who care at all about cities that are healthy, productive, and equitable places, to demand reform. Our work isn't done until a project as nakedly awful as the Inner-City Connector would be laughed off the drawing table.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.