Visions of a Future City

Our friends at City Observatory recently began a series about imagining the future city. Today we're sharing parts I and II from that series with permission from the author.

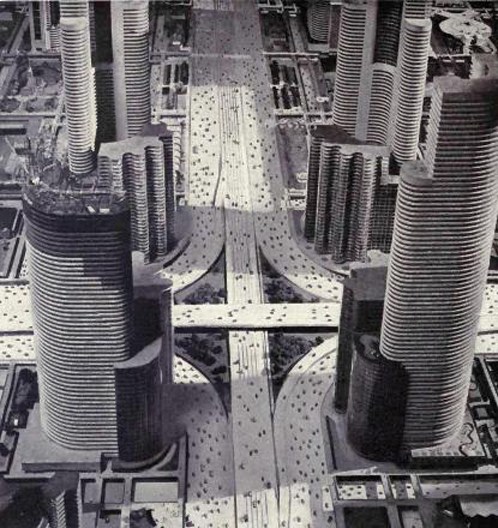

Vision statement, circa 1939.

Part I

In his recent presidential address to the American Economics Association, Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller talked about “narrative economics.” He argues that economists, like other disciplines need to begin to recognize that human cognition is structured around story-telling:

[N]arratives, stories that seem outwardly to be of entertainment value only, are really central to human thinking and motivation.

There’s something to this, and this week at City Observatory we’re exploring the question of what kinds of narratives are evident in the popular culture about cities and in particular the future of city living. Images can be a powerful way to communicate, and to sell ideas. Over the next few days, we will want to break away from our usual statistics heavy focus and talk explicitly about the images that are being used to describe cities and imagine their futures.

In the recent history of the American city, General Motors' famous Futurama exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair captured the imagination of Americans, and served as an iconic model of a new, auto-centric lifestyle that promised an end to traffic congestion and urban crowding. There’s no doubt that this image of a bright, mobile future appealed to a nation just recovering from the Great Depression. That image ultimately got reflected in policy–and pavement–with the enactment of the federal interstate highway program in the 1950s.

At this year’s Consumer Electronics Show–which is now the place for automobile companies to roll out their newest ideas, technologies and models–Ford presented its remake of the Futurama, which it called, “The City of Tomorrow”. A short video illustrates their vision. It starts out with an immediate future (presumably 2020s world) where there are autonomous cars, and bikeways, and forests built right up the edge of high-rises (we think they’re subconsciously channelling Vancouver BC as the model here).

See? The future is multi-modal.

Right off the bat, you’ll notice that this is a road and vehicle-centered view of urban space. Cars dominate. Sure, there’s a sop thrown to biking, pedestrians and transit, but notice this: All of the pedestrians, and cyclists are shown traveling in parallel to the cars. Walking and biking are just alternative ways of doing the same thing one would do, if one only had a car. And never mind that a cycle-track in the middle of a four-lane arterial would be a hellish experience, and difficult to access, or that the bulb-outs for the cross walk are grass, rather than paving (this is after all, a car company’s visualization of what it would be like to be a pedestrian). This image is strikingly consistent with so many illustrations of future cities, showing individual human beings as tiny specks, and showing a perspective of what the city will look like from someone floating somewhere in mid-air.

As the video progresses, Ford looks even further ahead, imagining what cities will look like decades from now when the full vision of vehicle autonomy is achieved. Now, small self-driving pods weave in and out, with computer-controls making sure that they don’t collide with one another (or with pedestrians, who simply walk across the street, sans signals).

In the not too distant future?

Clearly Ford is channeling some earlier thinking by MIT proposing that we do away entirely with traffic signals, and have cars flow steadily through intersections in all directions, with the speeds of individual vehicles controlled to allow gaps to open up and traffic to cross, marching-band style.

But who’s to say that Ford’s vision doesn’t actually morph into something more like the dystopia depicted in the 2008 Disney-Pixar movie, Wall-E. Blob-like humans carted everywhere in floating electric reclining chairs with view screens permanently set in their line of vision.

Advance images from next years CES?

This is one image of what the future of transportation might look like. But there’s a real question as to whether anyone would want to live in such a place. As we’ve pointed out at City Observatory, Americans are now paying an increasingly large premium to live in places that are highly walkable, where they don’t have to drive so much. And more people, especially well-educated young adults are choosing to live in close-in urban neighborhoods. A city awash in vehicles and optimized for movement may have precious little reason for people to come, to stay, to work, or to live.

What this all boils down to is whether we build our cities as places to “be in” or places to “move through.” The automobile companies, and by and large technology companies and the engineering profession are all optimizing cities for moving vehicles. But as we’ve learned, a place that you can move through quickly, especially in a car (or private pod) is not a place that people typically want to spend time in. And while technologists in the car world are intent on pushing a vision of remaking the city in the image of ever-more sophisticated vehicles, the folks at car companies that actually have to sell something today are much more attuned to the fact that people really don’t want to live in this kind of place. We’ll present their images of how cities should work, and how people might live in them tomorrow.

As the largest car company in the world tries to sell the best-selling car in the world to the next generation of consumers, it recognizes that it has to tell a story not about cars and driving, but about entrepreneurship, eating, hiking, biking, and hanging out in urban places.

Part II

Ford’s preferred narrative of the places we’ll live is all about optimizing city life for vehicles. But how about a narrative focused on people?

Another big global corporation has, perhaps unwittingly, given us a very different vision of cities–and life. This other vision comes from Samsung, the Korea-based technology company. They’ve been running a long form (60 second) television commercial called “A Perfect Day.” It follows the exploits of a half dozen kids–armed just with bikes, skateboards, and of course Samsung Galaxy smart phones–as they roam around New York City. There’s a lot going on here. Watch the video and then let’s see if we can’t unpack the different—and in many ways radical—narrative it's proposing.

First of all, they are in a city. New York is front and center. This is not an anonymous or sanitized CG landscape. It's authentically and identifiably a city–a real city. And it's shown from the perspective of actual humans experiencing it on the ground.

They are traveling by bike. The first scene of this micro-drama shows a platoon of cyclists (and one lagging skateboarder) set out in the morning, traveling in a marked bike lane on a residential street (in Queens or Brooklyn). They round a corner onto a busy arterial, and then ride across the Williamsburg bridge to Manhattan.

They are un-supervised by adults. The demographics of the group are just a little too perfect: teens and tweens, black, brown and white, boys and girls. But strikingly no adult authority figure is present. A parent calls only as dusk is falling (call answered via wrist-watch, naturally), only to be somewhat dismissively told “almost home,” with that message punctuated with a chorus of “Love you, Mom!” from the ensemble.

They are hanging out in public spaces.They’re not in a den, a great room, a tech-laden suburban bedroom, or even a cosseted back yard. They’re on the streets of the big city. They’re taking their own 3D photos and then sharing their virtual reality headset with a complete stranger they meet on the street. They’re at a skatepark under another towering bridge. They spend the afternoon hanging out at a public pool.

They are having experiences. The kids are recording and sharing their experiences with their Samsung devices. But in every case, the technology is incidental or subservient to the experience.

So here, in a nutshell, we have something that actually resembles a compelling future vision of cities. It includes technology, a little. But it isn’t about autonomous self-driving cars, or about side-walk internet kiosks or ubiquitous electronic surveillance.

Our vision of cities ought to be about the joy and wonder of the experiences we can have in them, not obsessing about the plumbing of moving people and stuff to and fro. For too long we’ve optimized our cities for the vehicles moving through them, rather than the people living in them. Samsung, or at least its creative agency (Weiden and Kennedy) gets this.

“If we have a story that centers on technology, vehicles and frenetic movement, we can remake our world in that image. If, instead, we have a story that embraces experience, and place and freedom, we’ll get a very different world.”

We’re not the only ones who were struck by this ad. Writing at her blog, Free Range Kids, Lenore Skenazy asked “What is this amazing Samsung ad trying to tell us?” The answer is pretty clear: If a city is a place where kids can roam and play, what else does it need to do?

Why narrative matters

In his Presidential Address to the American Economics Association two weeks ago, Nobelist Robert Shiller presented his thoughts on what he called “narrative economics.” Human beings are not the cold rational calculators they’re made out to be in traditional economic modeling. Instead, Shiller argued, human’s are hard-wired to visualize and understand the world through story-telling: We really ought to be called “Homo Narans.” That’s why getting the story right matters so much. If we have a story that centers on technology, vehicles and frenetic movement, we can remake our world in that image. If, instead, we have a story that embraces experience, and place and freedom, we’ll get a very different world.

It’s ultimately debatable whether Samsung’s version of “a perfect day” is one that everyone would agree with. But its an example of the kind of vision that might guide us, as we think about the kind of places we want to build. We should be deliberate in choosing our preferred narrative.