The Art of Decline

It's Public Art Week at Strong Towns. For the next few days, we'll be discussing the value of art in public life, the impact of public art on our neighborhoods, and how to ensure that public art is created by and for the people, not through a top-down process.

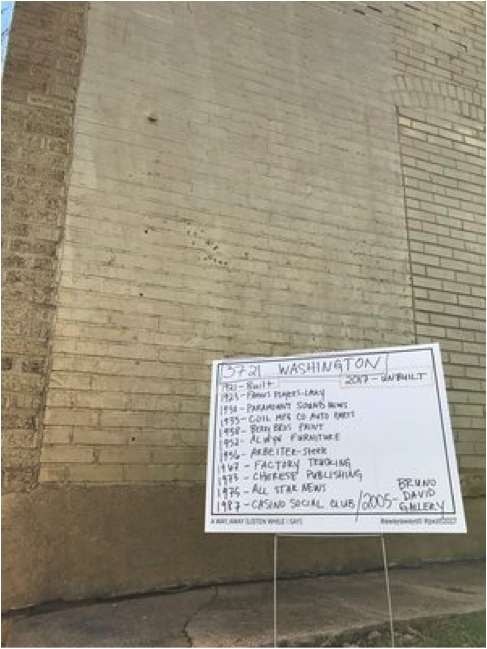

On an empty lot in St. Louis right now, by what used to be 3721 Washington Avenue, there’s a mountain of early 20th century brick, corralled by a chain link fence and baking in the late-May humidity. It looks like the refuse of a construction project, and it is: a building was recently demolished a few yards away, and this is what remains of it. If you don’t know what you’re looking at, you might not even pause when you walk by. You might not notice the glint of gold leaf, here and there amongst all the hot red clay, the dull plastic sheeting, the ash of old shale.

It’s my favorite piece of public art in my city.

A Way, Away (Listen While I Say) is an ongoing project by Chicago based artists (and architects by training) Amanda Williams and Andres Hernandez. It was commissioned in part by the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, which is housed in a concrete Tadao Ando masterpiece directly across the street. They were also the owners of the now-demolished building at 3721 that provided the inspiration and the materials for Away, A Way.

Via Pulitzerarts.org.

The story of 3721 Washington is a familiar one in St. Louis, a city made of swiftly aging brick and full of demolished lots like this. A standard engineering inspection revealed that the building was crumbling. The structural deficits were too great to repair. The inspector urged the landlord to condemn it.

But when you remove a building, what is lost?

Before it was a patch of new grass next door to a heap of bricks and ash, 3721 Washington Avenue was an empty building, covered two stories high in gold paint: the first phase in the Away, A Way project.

Before that, it had been Bruno David Gallery for eleven years, an exhibition space largely dedicated to the work of emerging artists unlikely to be shown in the museums across the street. It was also the only small business storefront on its stretch of Washington Avenue, otherwise lined with early 20th century mansions and home-to-office conversions, along with a handful of large-scale performance halls and museums (and the parking lots that come with them in a midwestern city like mine.) If you talk to some local urbanists, you’ll find a lot of them are critical of the foundation’s decision to level the building without a clear plan to rebuild. They don’t understand the choice to leave an important arm of the city’s ostensible arts district with yet another vacant lot, flanked by concrete and empty sidewalks where people don’t have much reason to walk unless they know exactly where they’re going.

Bruno David was one of a vanishing number of small scale gallery spaces in the whole city. Bruno David is also a person: he’d put $10,000 worth of improvement into the building just before the inspector told him it all had to come down. I know dozens of people who have shown there, fresh off MFAs at Wash U and sipping plastic cups of Pinot Grigio at their first opening. Those stories aren’t gone, exactly. But they’re not physically in evidence anymore.

And that’s not even to mention the other things 3721 has been in its history, and all of those places’ stories: a social club, and a newspaper office, a steel company,, an auto parts store. A pile of brand new bricks in 1921, sitting in the sun just like they are now.

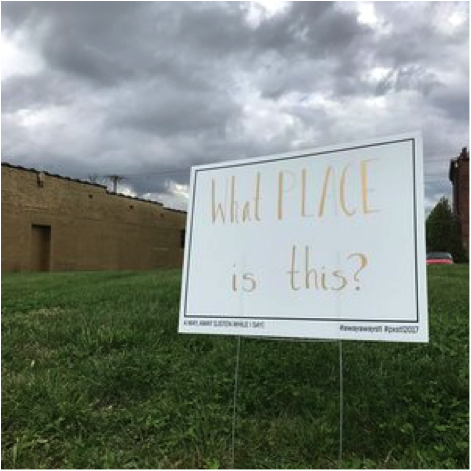

Williams and Hernandez began the first phase of their project by inviting neighbors, residents and anyone who had a relationship to the space at 3721 to “mark” the building alongside them. The instruments of that marking were simple: gold paint on the brick facade, hand-made yard signs in the lot next door.

Gold-painted brick and signs are common enough in this city, still visibly grappling with the aftermath of Mike Brown’s death on graffitied walls and in front yard gardens. Signs that say "Black Lives Matter" and "We Must Stop Killing Each Other" are still in evidence on most residential blocks (though which sign you choose generally depends on which neighborhood you live in.) These things are common enough that they’ve faded into the fabric of everyday life, by now. You don’t even pause to look anymore.

In a sense, the first phases of A Way, Away have given us a deliberately camouflaged piece of public art, one that doesn’t declare itself with eye-grabbing colors or sleek, out-of-place materials. If you don’t know the story, it could easily vanish into the background. That seems like it’s part of the point.

We’ve become so used to decline in our cities. We’ve become used to the dialogue about decline, too. We talk about it as an inevitable thing. Markets shift. Values drop. Buildings are demolished and lots sit open, the crabgrass crisping under the frost. We walk by and, at most, we call it a shame. We don’t stop to look.

But what if we aren’t the passerby in this story? What if we lived inside those walls, or next door? What if our money or our time or our energy or even just our gaze were invested in that space? What if we stopped on a cold day to run a paint roller over a plywood-sealed window and talk to a neighbor about what was once there?

And what if we recognize that if we live in a city, we’re never just the passerby, even if we’ve come to think of ourselves this way?

The second phase of A Way, Away (Listen While I Say) did not gather any neighbors outside in the cold for conversation over paint trays and sharpies. It was done by a crane. Every gold brick was torn down, and scooped by a mechanical arm onto the concrete pad in the lot next door.

But the phases yet to come will be different. Williams and Hernandez plan to distribute the bricks throughout the community, re-incorporating them into sidewalks, buildings, design projects, meeting makers and creating connections as they go. Then they’ll reshape the topographical contours of the empty lot, and heal the scar by regenerating the green space around it. They will talk and make and engage with the people they meet, and with the materials they excavate. They will create something that you can’t necessarily see, but you can certainly feel: a halo of connections and stories, hovering over an empty lot where the landscape has been subtly altered.

Via Instagram

The Bruno David Gallery has moved to an new space in an inner-ring suburb. The Pulitzer is mounting a new show. After Williams and Hernandez’ work is done, it will likely be razed and re-dedicated to a new public art project by the Pulitzer. All of this will change.

We think of buildings as permanent, especially if we’re not the ones who build them. We think of public art as a mural that interrupts a gray wall, not a pile of bricks or a curve in the terrain, not the stories of the people who made something in a space, or the neighbors who paused and stepped out of their front doors to ask a complicated question: What’s all this?

Away, A Way, (Listen While I Say) challenges these assumptions about land and art, value and worth, building and unbuilding. And it challenges us, too, to look at ourselves, and how we think of our role in our city’s placemaking—a phrase that, as architect and urbanist Walter Hood points out, “implies that there’s nothing there.” There is something there, even on empty land, and you are someone who has shaped it, the piece seems to say, even if it says it in a whisper. Even if all you do is walk by without seeing it at all.

(All images and video by Michael Thomas via awayaway.site unless otherwise noted.)