New bike network scoring tool turns up some surprises

The following guest article comes from PeopleForBikes.

According to the new PlacesForBikes Bike Network Analysis, the country's best low-stress bike network by far is in Rexburg, Idaho. (Image source: Google Earth)

It takes many things to build a good city for biking, but one of them is indisputably a nice mellow network.

Just as the car boom of the 1920s was made possible by new continuous networks of paved roads, the growth of biking in the next decade will depend on building continuous networks of wide or protected bike lanes, off-street paths and low-traffic streets.

Just as importantly, bike networks need to go places — they need to connect people to each other, to jobs, to public recreation and services, to private businesses.

The nonprofit I work for, PeopleForBikes, has just made the first attempt to measure and compare local bike networks on a nationwide scale.

The top 20 cities by Bike Network Analysis score.

The new PlacesForBikes Bike Network Analysis is a first-of-its-kind project and a work in progress. Using OpenStreetMap (a sort of Wikipedia for online maps) and the widely respected "level of traffic stress" methodology developed by Northeastern University's Peter Furth, we've developed digital records of the biking networks in 299 U.S. cities and assigned a numerical score to how well each one connects people to places.

To determine the stress level of a street (including its intersections), the BNA considers lane counts and widths (for both bike lanes and general travel lanes), speed limits, traffic signals and the presence of parked cars.

BNA scores by Census block within Washington D.C. The best bike network connections are in bluer areas.

PeopleForBikes is releasing a set of comprehensive data-driven city ratings this fall. BNA score will be one of several components.

"What it measures is whether people can get to key destinations on a low-stress network," said Jennifer Boldry, Ph.D, director of research at PeopleForBikes and lead creator of the BNA. "That's kind of different from how good it is to bike, because I think there are many elements to the enjoyability of a bike ride."

Here's a short guide to exploring everything the BNA currently has to offer, including a video.

A surprise star for low-stress biking: America's small towns

Biking stress levels on the street grid of Alma, Michigan.

One interesting phenomenon turned up by the BNA: many of the top-scoring cities have very small populations. Some of them hardly have any actual bike lanes.

"There's a handful of kind of small towns, unusual suspects that do really well," Boldry said. "In all of those places, you have a ton of low stress connections in big bulk right in the middle, and that's where all of the destinations are."

Average network stress by Census block in Troy, Ohio.

Clustering small businesses, public destinations and multi-story housing on two-lane main streets — the standard development pattern when many of the country's small towns were built — turns out to be a good way to make a city bikeable.

"I think it advances the discussion around the importance of land use," Boldry said. "I think we're going to see that getting people to ride from A to B - they have to have a B."

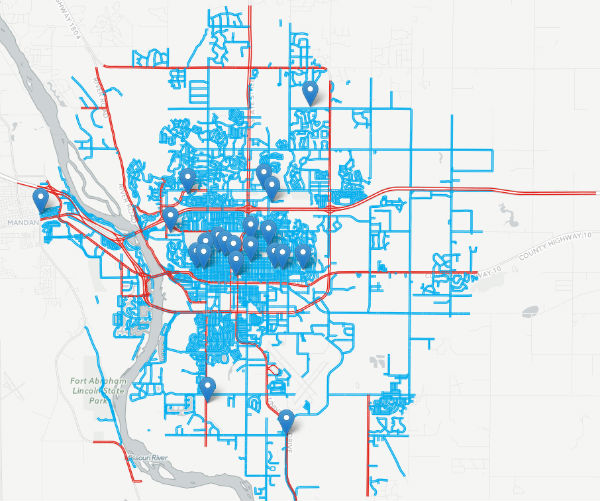

Schools in Bismarck., N.D., and their connections to the city's biking network. The highest-stress streets are in red.

The Bike Network Analysis is only as good as OpenStreetMap's data

The BNA is far from perfect. One major shortcoming: it's blind to destinations that haven't been entered in OpenStreetMap.

For example, the city of Bismark, N.D. receives the country's eighth highest BNA score — but that's in part because OpenStreetMap thinks the city has zero retail outlets, doctors, dentists, pharmacies or social services. Therefore, BNA doesn't attempt to score connectivity to those destinations.

Bismarck also has a BNA score of 54 for bike access to transit — more than twice the transit score for Washington D.C. or San Francisco, Calif. Bismarck's bus transfer stations may happen to be located on low-stress streets, but it's debatable whether its score reflects the experience of combining bike and transit trips.

Another issue is that the BNA can't see beyond city limits. For example, Alma, Mich., population 10,000, gets the country's No. 2 BNA score: 71. That's bolstered in part by its nearly perfect retail access score of 91. But Alma's retail score ignores the city's most important retail outlet, the Walmart Supercenter on high-stress Alger Road, because it sits just north of city limits.

Temple City, California. (Photo: Streetsblog LA.)

PeopleForBikes wants feedback

Boldry says some issues like these are inevitable, and others may be fixable.

"The way we're thinking about it right now is that the maps and scores are truly a beta test," she said. "We're in sort of a review period until July 14, where we're soliciting feedback from cities and advocacy and anybody who is interested in this sort of thing."

You can help us improve the scores by completing this survey.

PeopleForBikes will pull fresh OpenStreetMap data and recalculate BNA scores in time for the city ratings this fall. But Boldry said the BNA methodology is likely to keep changing.

Ultimately, the goal is to make it easy for any U.S. city to do basic analysis of its network, find its weakest links, and measure the payoff from improving them. "I think we're interested in making it as good as it can be, and for that to be true it has to be evolving," Boldry said.

Related Stories

About the Author

Michael Anderson is a staff writer at PlacesForBikes—a PeopleForBikes program to help U.S. communities build better biking, faster. You can follow them on LinkedIn, Twitter or Facebook or sign up for their weekly news digest about building all-ages biking networks.

How a local bike trail went from being a fun “extra” for its town to an important part of the community’s transportation system.