Learning from a Non-Conforming Neighborhood

Nolan Gray is a Strong Towns member and writer for Market Urbanism. We welcome him today for a guest article about housing in his hometown of Lexington, KY.

Kenwick, Lexington, Kentucky. (Google Maps)

“Many of our best neighborhoods would be illegal to build today.” This single sentence offers powerful insight into the challenge facing American cities, exposing, in one breath, the perverse restrictions involved in conventional zoning and subdivision regulation. In many old neighborhoods, built form, lot dimensions, and land uses are "non-conforming", meaning that they are non-compliant with land use regulation. One sees this line frequently across the urbanism blogosphere, usually coupled with an explanation of how outstanding neighborhoods like the French Quarter or Beacon Hill fly in the face of conventional urban planning.

But the problem is worse. Forget about the superstar neighborhoods—even most run-of-the-mill inner suburban neighborhoods would be next to impossible to build today. You probably have a few such neighborhoods in your city—neighborhoods just outside of downtown where structures cover most of the lot, where lots are perhaps slightly narrower and smaller, and where single-family homes casually mix with other uses. Understanding this variation is key to freeing up developers to replicate what works in new neighborhoods and to unlocking the potential of some of our best existing neighborhoods.

Let’s take an example from my hometown of Lexington, Kentucky. Kenwick is a wonderful inner suburban neighborhood to the southeast of downtown. The neighborhood was originally built out in the 1920s and 1930s, though waves of teardowns and rebuilding—particularly post-World War II—have gradually changed the appearance of parts of the neighborhood. While Kenwick was once serviced by the private streetcar, car-ownership was fairly widespread at the time this neighborhood was built. The neighborhood’s streets follow a tried-and-true grid pattern, with blocks measuring 100 meters in depth and 350 meters in length.

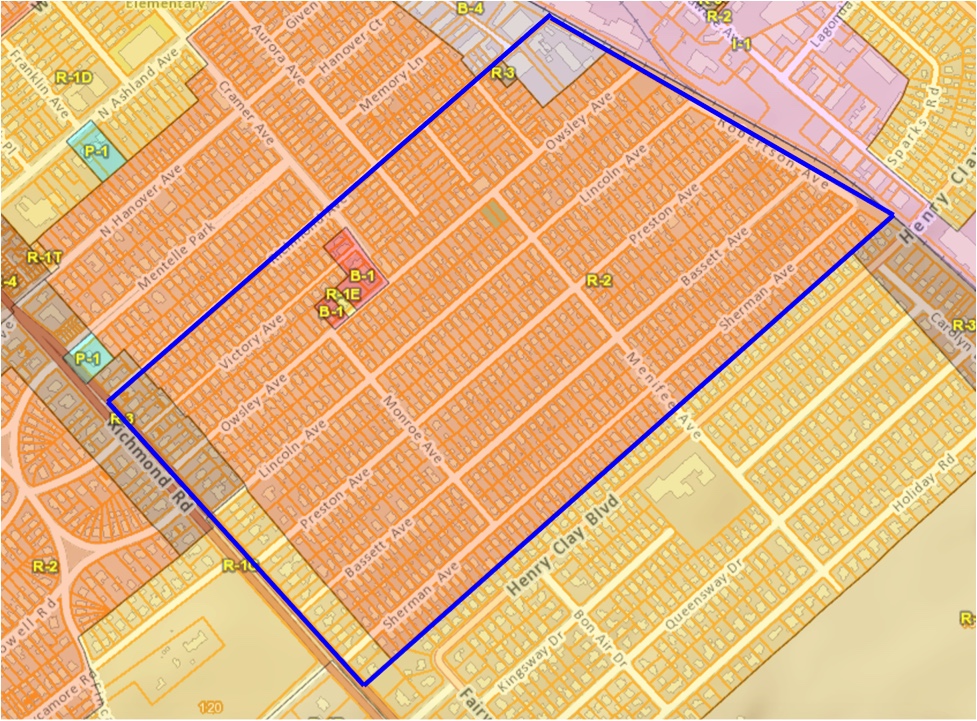

The zoning of Kenwick. R-1 mandates single-family homes, R-2 townhomes, R-3 limited multi-family housing, and B-1 limited commercial. The B-1 in the center is a limited carve out for Wilson’s Grocery and neighboring parcels. Many other commercial uses are zoned R-2 and are non-conforming. (Source: Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government.s Department of Geographic Information Systems)

Until recently, Kenwick, particularly north of Monroe Avenue (see the parcel map above for labelled streets), was a mostly working- and middle-class neighborhood. The area to the south of Monroe Avenue is and always has been wealthier. While the neighborhood's character is changing thanks to an influx of young professionals attracted to urban living and an outflux of downsizing retirees, Kenwick remains a diverse community both in terms of income and associated factors like age, race, and family structure. Yet as Kenwick grows in desirability, it will also need to grow and adapt to rising demand for housing. While rents for townhomes and apartments are still affordable, home prices have increased dramatically over the past decade. Happily, the ability to adapt is built into Kenwick’s urban DNA, if only planners would allow it to express itself.

There is a lot about Kenwick’s urban form that I came to love while living there. The relatively high density of the neighborhood—6,865 people per square mile, compared to a citywide density of 1,087—means that for many residents, friends and family are close by and neighborhood services like groceries, elementary schools, and churches are sustainable. This relatively high density is thanks in part to the neighborhood’s widespread non-conformity with its contemporary R-2, or “Two-Family Residential” zoning restrictions.

In terms of built form, compliance with the required side setbacks is extremely uncommon—homes rarely sit more than five feet from the side of the property line despite a required side setback of six feet. Many homes, particularly those built before World War II, lie well within 20 feet of the front property line, despite a required front setback of 30 feet. While seemingly trifling, these small setback transgressions minimize the space that is wasted on yards and free up more space for additional residential units. A general disregard for front setbacks also allows front porches to engage with the street.

A parcel map of Kenwick today. Note that lots northwest of Lincoln Avenue are smaller and irregularly shaped. These properties were largely platted before the citywide zoning and subdivision ordinance in 1930. Properties to the southwest of Lincoln Avenue were largely developed after 1930 and, by contrast, are almost universally the same size: 7,501 square feet, just meeting the required minimum area. Since developers are just meeting the bare minimum, it’s a safe bet that the regulation is forcing larger lots than the housing market of the time would otherwise have produced. (Source: Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government.s Department of Geographic Information Systems)

Kenwick’s non-conformity with required lot dimensions also helps keep densities high. Officially, lots in an R-2 district must have at least 60 feet of street frontage (i.e., the edge of the lot abutting the road must be 60 feet long) and lots must be at least 7,500 square feet in area. Particularly in the older parts of the neighborhood to the north, it’s common to find street frontages below 50 feet, meaning that lots are narrower than what is required by zoning. Even more common are lots smaller than the 7,500 square foot minimum. While the standard lot size to the south is approximately 7,501 square feet—this area was mostly built out after 1930, when citywide subdivision and zoning ordinances were adopted—many lots lie well below 5,000 square feet. At least one lot is 2,592 square feet, less than half the mandated lot size. Lot coverage, or the percentage of the lot that is covered by a structure, is much higher than in outer suburban developments.

Not “tiny homes,” just regular homes that were built for regular people on regular budgets. Vacant lots in the neighborhood could be split and developed into houses like these, if land use and subdivision regulations allowed it. (Source: Google Maps)

While the homes are small by today’s standards, these are not “tiny homes” or “microunits” or any other such real estate novelty. These are modest buildings on modest lots. For much of American history, they were simply called “homes,” even if lacking the excessive yards, sprawling floor space, and two-car garagesthat are often required today by zoning and subsidized by the federal government.

Vertical townhomes are underrated. (Source: Google Maps)

Crucial to Kenwick’s urban suburbanism is its unique mixture of uses. Unlike the new master planned residential subdivisions in the outer suburbs, Kenwick offers a mixture of housing types, public services, and commercial uses along a connected urban grid. While Kenwick’s official zoning only permits townhomes—specifically, two residential units connected by a vertical wall on each lot—the neighborhood in fact hosts dozens of small apartments and stacked townhomes. Most pre-zoning apartments and townhomes simply look like large homes from the outside, a popular pre-zoning development that can also be seen in other Lexington inner suburbs, including Woodland, Ashland, and Chevy Chase.

Small apartments abutting homes. Both are flaunting setback rules, which keeps the street at a human scale. (Source: Google Maps)

Yet residents have also quietly added dozens of new units post-zoning. While often hidden from the street, Kenwick residents have built dozens of accessory dwelling units, or “granny flats.” These units often take the place of detached garages or sheds and are usually rented out by the owner of the home. As detached units are technically not permitted under Kenwick’s current zoning, the builders of these units likely had to bypass official planning review in most cases. These units add affordable housing to Kenwick and often help to keep elderly parents and young adult children close to home, both of which help to increase diversity and activity within the neighborhood.

Bread, milk, beer, and the serendipitous social interactions among neighbors that keep a liberal society functioning—don’t underestimate what a neighborhood grocer can offer. (Source: Google Maps)

Beyond residential uses, Kenwick also hosts a welcome mix of non-residential uses. Kenwick Park, the Kenwick Community Center, Ashland Elementary School, and various churches act as hubs of neighborhood social activity that most residents walk to. Most unusually, the neighborhood also hosts a variety of commercial uses, including local shops and groceries, home-based businesses, and offices. Some of these uses enjoy special zoning carve outs, like Wilson’s Grocery. But most seem to be either legal or illegal non-conforming uses. The neighborhood's local groceries keep daily necessities like bread, milk, and beer—I can recall, once a week an older resident of my street used to walk to Thriftway Food Mart at 9:00 AM for a case of Milwaukee’s Best—and serve as hubs of community social interaction.

A backyard transformed into a local business and an additional unit. Watching the owner of the home in front work on this addition for over a year offered a daily reminder of the power of small projects. (Source: Google Maps)

Many homes also seem to operate as the headquarters for small local businesses—a computer repair shop, an art studio, and general contractor operated openly within a block of my home. While technically illegal under current Lexington zoning, these kinds of home-based businesses add welcome activity and local flavor to the neighborhood. They also help minimize start-up costs for entrepreneurs, which goes a long way toward enhancing economic opportunity for residents. Buildings that were once clearly commercial yet have been converted to residential—a switch required by the neighborhood’s R-2 zoning—indicate that this unplanned mix of residential and commercial was likely a normal part of life in Kenwick from the beginning.

This confluence of non-conforming elements create the kinds of positive feedback loops that build great neighborhoods: more Kenwick residents walk and ride bicycles, since they are within easy walking and bicycling distance of public services, commercial uses, and friends and family. This active and interesting street life in turn encourages residents to socialize and “people watch” on their porches and at local parks and shops, which helps to keep Kenwick safe and interesting. I can attest to this dynamic as a reminiscing former participant: on many cool summer evenings, I played my part, reading and having a few beers on my front porch to the ambient suburban bustle of neighborhood kids roving around, of residents visiting friends with dinner supplies from Wilson’s or Thriftway in tow, of commuters returning home from downtown by bicycle, of the general contractor down the street consorting with staff about tomorrow mornings job.

“The power of small increments to allow Kenwick residents to grow and adapt should not be underrated.”

The subtle joy of this non-conforming messiness is hardly limited to the superstar neighborhoods we often have in mind when we discuss the cost of conventional land use regulation, and yet it remains unavailable to the “conforming,” low-density, single-use neighborhoods of Lexington’s outer suburbs. As is the case with so many of Kenwick’s non-conformities—the disregard for bulk and lot restrictions, the addition of new accessory units, the small businesses that keep the neighborhood abuzz—the power of incremental steps to allow Kenwick residents to grow and adapt should not be underrated.

This speaks to the strength of “non-conforming” neighborhoods like Kenwick: they contain within themselves the capacity for self-renewal. The legal non-conforming elements of Kenwick that arose before zoning—the small setbacks, the high lot coverage, the tight lots—are indeed interesting. One would be hard pressed to try to build an urban neighborhood like Kenwick elsewhere in Lexington, as the city is mostly zoned for single-family houses and rural estates. But what truly keeps Kenwick alive is its ability to change and adapt, both within and beyond the restrictions of contemporary planning. Townhomes are being built on lots that once hosted single-family houses. New accessory dwelling units have naturally sprung up in the backyards of lots as demand for housing in Kenwick has grown over the years. Old commercial uses continue to thrive as new home-based businesses keep the streets alive.

You best start believing in informal accessory dwelling units, dear reader...you’re in one! (Source: Google Maps)

It is important to grasp how zoning transforms perfectly fine neighborhoods into legally ambiguous “non-conformities,” not only in order to help us understand how zoning might prevent the construction of new great neighborhoods, but also to understand how zoning holds back existing great neighborhoods. “Non-conforming” status makes securing permits and bank financing more difficult. Restrictions on density—setbacks, off-street parking requirements, minimum lot sizes—hinder the adaptive reuse of Kenwick lots for new urban development that conforms with the community's urban form. Use restrictions associated with Kenwick’s R-2 zoning prevent the legal construction of new apartments—which could help to moderate the rising cost of housing and keep Kenwick diverse—and the emergence of new, neighborhood-oriented businesses.

It’s one thing for a typical American neighborhood to end up “non-conforming” when the rules change. But what does it mean when the residents of a typical American neighborhood continue to peacefully disregard the dictates of zoning, maintaining legal non-conformities and adding new illegal non-conformities? The industrious residents with their small plans understand something that our centenarian Euclidian zoning system doesn’t: that great neighborhoods must change, that desirable neighborhoods must add new housing, and that it's natural for new businesses to come and go, mixed in with existing uses. Perhaps the greatest harm inflicted by zoning is not that it prevents us from recreating our best neighborhoods, but that it prevents our best neighborhoods from recreating themselves.

Update: According to Fayette PVA David O'Neill, median sales prices of houses in Kenwick have seen a ~50% increase, making it has been the most desirable neighborhood in Lexington for the past 20 years or so. How's that for revealed preference?

Related stories

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nolan Gray is a writer for Market Urbanism. You can follow him on Twitter at @mnolangray.