The Millennial Housing Shortage Fallacy

Pete Saunders is a planning consultant and journalist based in Chicago. He blogs at The Corner Side Yard and today's article is republished from his blog with permission. It's a few years old but it rings quite true today. Pete prefaced its republication:

I'm beginning to believe we're at an inflection point when it comes to our nation's cities, gentrification and race. Many of the low to moderate income neighborhoods that were largely white in major cities have been revitalized. Many of the low to moderate income neighborhoods that are largely minority—particularly African-American—are patiently waiting their turn, yet nothing is happening. What's happening instead? Calls for upzoning as an affordable housing solution, or humorless and data-sourced attempts at letting potential gentrifiers know what areas should be avoided.

The continued revitalization of cities depends on breaking through this inflection point -- but it may require a social and cultural transformation in this nation far bigger than we're even ready to acknowledge.

Andersonville, a trendy and increasingly expensive neighborhood in Chicago. Source: Kevin Zolkiewicz

There is no shortage of housing in most U.S. metro areas. There is a shortage of housing in the areas most attractive to today's young and affluent urban pioneers. Their efforts to increase supply in cities—in the most desirable areas—are misguided and could ultimately cause more harm than good.

There is a spreading meme that the dominance of single-family zoning districts in major cities is artificially reducing housing supply. Economists like Harvard professor Edward Glaeser have been stating for some time that super-tight regulation of land use in large metro areas has depressed housing construction, through a complex mix of zoning districts, air rights, historic preservation districts or byzantine permitting approvals and NIMBY-oriented residents Others, like Matt Yglesias, have made the same point, and it's becoming increasingly common among a growing group of young urbanists seeking to address their most pertinent concerns.

Admittedly, there is a shred of truth to this in many coastal metros, and in a select group of interior metros like Chicago. They are, in fact, not adding new housing supply relative to the demand for housing. Yglesias showed this in a recent article in which he suggests that the lack of recovery in the housing industry is a drain on the national economy. He uses two charts to make the claim; he compares the number of housing permits authorized between Houston and the San Francisco Bay Area:

and for Atlanta and Boston:

True enough, Houston adds more units than the Bay Area, and Atlanta adds more than Boston. But there are other factors contributing to that besides land use regulations:

- Geography. Boston and the Bay Area, among other coastal metros, are some of the most geographically constrained metros in the nation. Water and terrain limit the amount of buildable land in the most desirable coastal metros. This puts a bigger cap on the amount of development than anything the regulatory environment can do.

- Old vs. New. It's not entirely fair to compare metros that may now be of comparable size, but come from entirely different places over the last 60-70 years. The Bay Area's metro population in 1950? It was 2.5 million. Houston's was just 920,000. Boston's metro area population in 1950 was 3.5 million, while Atlanta's was just 727,000. Even though all are relatively comparable in size today, they certainly did not start from the same base.

- Redevelopment vs. Development. Developers who specialize in redevelopment — dealing with numerous owners to slowly packaging multiple parcels of land over time, dealing with demolition and cleanup costs, and obstructive NIMBY residents — have an entirely different playing field than those who specialize in conventional greenfield or large parcel development. Even in today's shifting development landscape, we have an abundance of developers who specialize in the latter, and relatively few who are competent in the former.

However, in answering his own question in a recent blog post, blogger Daniel Kay Hertz sheds some light on the thought process behind the growing meme:

Why are there no apartment buildings in your standard affluent single-family-home neighborhood, common in metro areas from Chicago to Kansas City to New York to Memphis? Not because people don’t want to live in them. Not because you couldn’t make money by building them. They don’t exist because they’re illegal.

The emphasis is added because it highlights the salient point, which can be reduced to this: "Why isn't there more housing where I want it?" Because there are plenty of apartment buildings with plenty of vacancies in other parts of the city. Let's fill those up, and then talk.

If young urbanists are serious about moving back to the city, maybe they ought to consider more of the city to live in. For every highly desirable attractive urban neighborhood, even in the most in-demand metro areas, there are just as many languishing neighborhoods that aren't even part of the conversation. For every Lincoln Park or Lakeview in Chicago that lacks affordable housing, there is a Garfield Park or Woodlawn with tons of it.

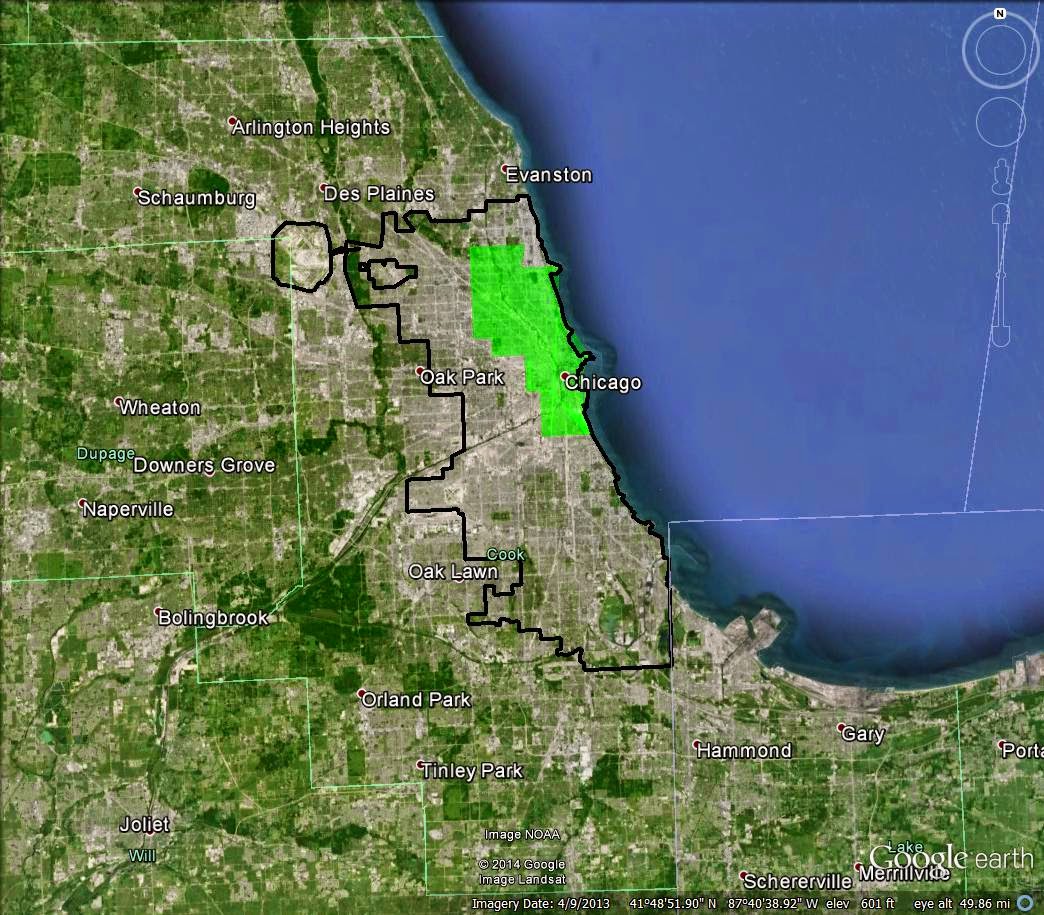

Let's dig deeper into Chicago. I recently wrote a post where I tried to define the differences between the most in-demand parts of Chicago with the rest of the city. In it, I identified what I called "Global Core Chicago":

The area highlighted in green corresponds roughly to the ten Chicago Community Areas (Chicago's officially designated neighborhoods) that make up Global Core Chicago. Let's see how it compares with the balance of the city, which could be called Rust Belt Chicago, on a few data points:

This data is from the 2012 Census American Community Survey. You know what I see? I see a "Global Core Chicago" that, in terms of density alone, already looks very similar to the most desirable urban areas in the nation, like New York, Boston, Washington, DC and San Francisco. Not only does this core have 55% more people per square mile than the remaining parts of the city, it already has 2.2 times more dwelling units than the rest of the city. A big factor in this disparity is the difference in household size — households in the global core are only two-thirds the size of those in the rest of the city. And this makes no mention of the income and wealth differences between the two parts of the city.

I don't believe we should be talking about expanding the global core at its margins. We should be talking about expanding development throughout the city. If young affluents are serious about returning to cities, they should consider Austin, Bronzeville, Woodlawn and South Shore, and not just Wicker Park and Logan Square. The same applies to every metro area in the nation.

“This push for more affordable housing in affluent city neighborhoods, because we like it there, is akin to the push for more suburban housing at the urban outskirts 60 years ago.”

We haven't learned. This push for more affordable housing in affluent city neighborhoods, because we like it there, is akin to the push for more suburban housing at the urban outskirts 60 years ago. "The demand is there! Accommodate our needs!" And that led directly to a disinvestment in cities from which we are only now beginning to recover from.

We must be very careful in what we ask for in the development of our cities. Simply requesting relaxed land use regulations so that more units will be built could result in serious unintended consequences. Doing so in Chicago, and in many cities around the nation, would result in a spurt of housing growth in the most desirable areas—and in the most desirable areas only. The global core would add far more units relative to the rest of the city. It would not reduce residential and economic segregation, it would increase it, and contribute to one of the most vexing problems of our cities today — the exploding bifurcation of our cities by race, class and opportunity.

Doing so would result in cities made up of contiguous enclaves of affluent, dense, walkable and self-sufficient communities. They would be beautiful, and they would be made up of the kind of development that is most preferable to me. Yet they would be adjacent to but wholly disconnected from half-empty expanses of impoverished, working class and middle class neighborhoods. I can't reconcile that in my mind.

Do we really want that? Can't we do better than that?

(Top photo source: David Hilowitz)