The Problem with Projections

Like several American cities, Cincinnati recently built and opened a streetcar. There was fanfare, there were high hopes, there were big ridership predictions. It cost $148 million.

But after one year operating, the streetcar has failed to come anywhere close to the ridership targets set by city consultants. In fact, the amount of people who rode the streetcar on opening day is still the highest amount of patrons the line has ever seen. The Cincinnati Enquirer reports:

Source: Cincinnati Enquirer

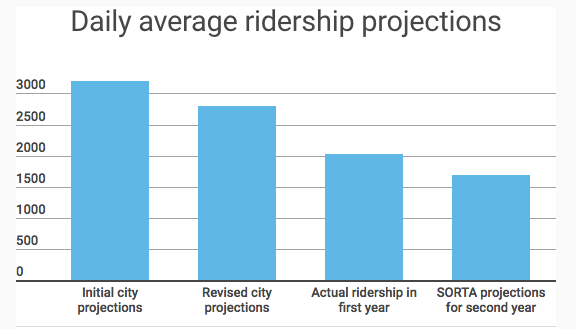

Within a couple weeks of its launch, it was clear the initial projections made by consultants for the city were wishful thinking. In 2011, consultants estimated the streetcar would see 3,200 rides each day. Last fall, those projections were lowered to 2,800 a day.

Those earlier projections did not take into account seasonal changes in use and other factors like holidays. SORTA's new projections do.

The most recent projections from SORTA run from July 2017 to June 2018 and estimate a total ridership of 609,300 or an average of 1,693 per day.

In other words, ridership projections have been nearly halved since they were initially made.

The Cincinatti Enquirer article also reveals some ridership datapoints that surprised those who planned the system and developed the projections:

- The streetcar is being used far more often as weekend transportation than for commuting to work.

- Streetcar use goes down in the winter months and back up when the weather warms.

Because the system was built to a finished state from the get-go, there’s a limited amount the city can do to respond to these revelations, and those responses (like buying additional cars to service busy weekend hours) are likely to be costly.

In contrast, an incremental approach to public transit like adjusting an existing bus system or opening a smaller scale van service could more quickly respond to changing needs based on the day and season by rerouting commuter buses onto weekend bus routes or relocating stops onto streets with warm waiting areas.

“This story from Cincinnati doesn’t so much reveal the risks of rail lines as it reveals the problem with projections and most cities’ reliance on them.”

But this story from Cincinnati doesn't so much reveal the risks of rail lines as it reveals the problem with projections and most cities' reliance on them. When we begin a conversation about a project with highfalutin, fallacious data, we easily fall into the trap of building that project around those predictions. Of course this streetcar will be financially viable because we'll have 3,200 people riding it each day!

If we approached transit from an incremental perspective instead of an all-at-once megaproject perspective (and yes, I consider something that costs over $100 million a megaproject, even if the streetcar route is only a 3.6 mile loop), we wouldn’t base our standard of success on ridership numbers. We’d be looking at how much the transit improved our town, how it helped get people to work and doctors appointments and grocery shopping, how well it used the small amount of money it began with to help the most amount of people. And where we saw success, we would expand the system. The goal would be getting people to their daily needs in an affordable manner that didn’t require driving, not filling up seats on a streetcar.

Towns big and small could stand to implement a strong towns approach when considering transportation access in their community. It isn't about how many lanes your highway has and how many seconds that might save on travel time. It isn't about how fancy your streetcar line is and how that will attract new users to public transit. It's about getting people where they need to go in an affordable, safe and quick manner that won't sink your town into debt in the process, or leave you stuck with a system that doesn't work the way you need it to.

(Top photo source: Rick Dikeman)

Why don’t the small things get funding?