Can a bike-friendly city be disability-friendly, too?

A few months ago, while spending my requisite billion hours per day browsing facebook, I ran across a pretty dumb meme:

I don’t usually devote much of my time to arguing on the internet, especially when I don’t know anything about the person who created the original post and especially if a silly photo of Canada’s national treasure of stage and screen (/rapper, I guess,) Aubrey Drake Graham, is involved. But there are only so many moments when the possibly-wonky urbanist stuff I’m passionate about penetrates the millennial meme-sphere and actually gets people talking about the way we build our world. The post appeared on the feed of a friend who isn’t a biking nerd; I’m not certain I’d ever seen them post about anything adjacent to urban design, period. And every comment on the post was some variation on “Amen,” or “I’d never thought about this before, but I totally agree.”

In a decade plus of riding a bike in cities, I’ve run across a lot of reasons why some people unilaterally hate bikes and bike lanes, many of which boil down to an unexamined attachment to auto-centric development, a lack of basic compassion for people without access to (or passion for) motor vehicles, or a simple ignorance of any alternative to a world built for cars. (And sometimes, a combination of all three.)

But I’ve never run across someone who opposed bicycling and pedestrian infrastructure specifically because they perceived that it harmed life for people with disabilities. That’s not to say I’d never considered the plight of a mobility-limited person in public space; one of the reasons I became passionate about biking and walking, specifically, was because I recognized how intensely isolating auto-centric development made the lives of so many people I care about, especially those with physical impairments or special mobility needs.

Here are a few things I think this meme gets wrong—and why, if we want to build a better world for people with limited mobility, we might need bike lanes more than ever.

1. “Bikes have the second-lowest road space utilization efficiency behind single occupancy cars.”

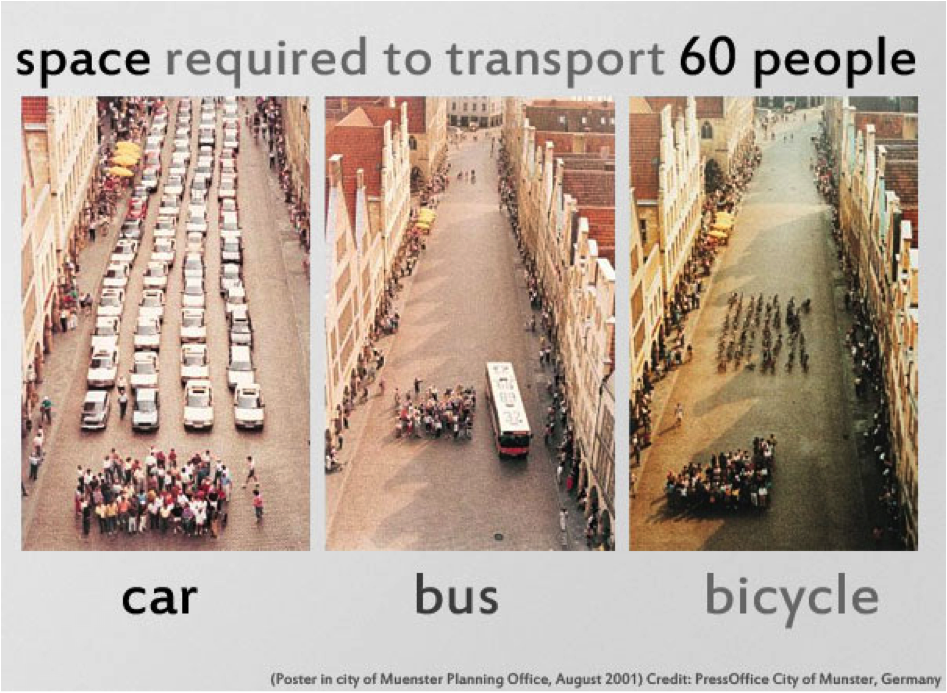

Just to get this out of the way: if you’re at all interested in street design, there’s a high probability that you’ve run across a variant of this image at some point.

It’s famous for a good reason: it’s an easy, visual way to showcase just how much space we need to build if we insist on putting every commuter in a separate car of their own.

But the author of the Drake meme saw something different: a herd of unruly bikes, sprawled over a square of asphalt almost three times the area as that of the bus. I can’t dispute that observation; a human being on a bicycle will, indeed, take up more room than one person seated next to a neighbor on a city bus. But as much as I love an occasional critical mass ride, bicyclists don’t tend to ride in bus-sized packs for everyday commuting.

And even if they did, road space utilization is a truly terrible metric by which to judge a mode of transportation, at least when taken in isolation from any other factors. For one, emphasizing square feet of asphalt used in our transportation conversations buys into the wildly incorrect assumption that road space is a scarce and precious resource that we must jealously guard. If we’re scared of losing lane space because we’re scared of ending up in traffic on a few key roads, we need only look to the miles upon miles of empty asphalt arterials that we indebt our cities to build and maintain, often without even considering data-responsive solutions to better distribute that traffic, like tolls, before we freak out and start adding even more lanes to solve the problem (which it doesn’t). If the fear of bikes spreading out and taking the lane has to do with spreading damage to the edges of our roadways, I have some really bad news for this meme maker.

But when it comes to providing transportation options for our neighbors with handicaps, hyper-focusing on road space utilization is even more dangerous for a simple reason: it ignores the infinite ways we build in response to the dominant mode of transportation that’s taking up space in those lanes. Whether we’re discussing America’s decades of auto and gas industry-influenced suburban development or the tight, people-scaled streets of towns around the globe where cars aren’t allowed at all, the way we move through our cities shapes everything beyond our streets as well—and the world that results from cars might not be the most friendly to those who have limited mobility. (More on that later.)

2. “[Bicycles] are largely inaccessible to large swaths of the population with disabilities.”

A military veteran uses an adaptive bicycle. (Source: U.S. Air Force photo/ Senior Airman Dennis Sloan)

First, a few numbers: according to the US Census, about 19% of the country’s population has some form of disability. About 12.5%, or one in eight Americans, have a mobility impairment, and about 8.5% of Americans use some form of mobility assistive device, like a wheelchair, walker or cane. That’s not an insignificant portion of our citizenry, and it’s crucial that we provide viable transportation options for every one of those people.

But the assertion that bicycles are “largely inaccessible” to the entire mobility-impaired community is just false. There’s an incredible variety of adaptive cycling options, from hand cycles for those with lower limb impairments, to tricycles for those with balance issues, to tandem recumbent bicycles for visually impaired cyclists to ride with seeing friends, and so many more. Some adaptive cycles are covered by insurance. (Here’s a guide on getting coverage through Medicaid). In Wauwatosa, WI, a new bike share program became the very first in the country to offer adaptive cycles along with the rest of their fleet.

And no matter which way you cut it, the cost of an adaptive cycle doesn’t outstrip the extensive costs of owning an adaptive motor vehicle; installing wheelchair accessibility equipment into a van can cost $10,000-$20,000 for the conversion equipment alone, never mind the cost of the gas, insurance, basic maintenance, and the car itself. That’s not even taking into account people who can’t drive at all due to “invisible” disabilities such as severe epilepsy. Strong Towns member Eli Damon uses a bike for transportation precisely because he has a visual impairment and is not able to drive a car.

3. “[Bicycles’] limited range doesn’t help to connect neighborhoods cross-city.”

So...because we built a spread out world for cars, we can’t possibly bike through it?

I’m being glib, but nothing bugs me more in conversations with biking haters than the idea that you can’t really expect anyone to ride a bike, because biking in the street isn’t safe, and bike lanes don’t go anywhere, and have you even tried biking lately, because it’s scary and hard and it takes so long to get anywhere you want to go...

It bugs me because in many of our cities, all of those statements are true. But we can change every one of them. The fact that we need to drive miles and miles across town to meet our basic needs is not often a natural feature of our landscapes; usually, it’s a choice we made, and a bad one. And we can unmake it. There are infinite low-cost, incremental ideas we can use to make our development pattern more compact and our neighborhoods more habitable for human beings, rather than cars.

And for what it’s worth; this wimpy, not-terribly-athletic biker (a.k.a. me) biked five slow miles to work every day for years in about twenty five minutes, passing through about five cross-town neighborhoods on the way. Give it a try; the range of your bike may not be as limited as you think.

4. “Cities over-focusing on bike accommodation risk impeding and atrophying more accessible and connective public transportation, like trains, and especially busses [sic], which must compete with bikes’ terrible road space efficiency.”

Buses and bikes can provide a myriad of transportation options on their own or together for people who can't or don't want to drive. (Source: Oregon DOT)

Of all the misstatements in these two jam-packed sentences, this is the one that really gets under my skin.

But to do my due diligence, I went searching for any evidence that extending bike infrastructure represents a barrier to extending transit options. I tried to find that mythical city where an evil bike advocacy organization (perhaps the infamous bicycle lobby?) swooped in and claimed the money and (ugh, this again) road space that should have rightly been designated to a train or a bus.

I didn’t find it. What I found instead were images of shared bicycle/bus lanes, and bus rapid transit systems that developed in seamless tandem with bike lane systems, saving their cities billions. What I found was significant overlap between the country’s top cycling cities and our top transit cities.

While I’m not sure an official study has been conducted correlating the development of good pedestrian and bicycling infrastructure with good transit, the experiences we all have from living in cities and towns with and without transit can, at least somewhat, can speak for themselves. When cities listen to their citizens and truly build a transportation system responsively and from the bottom up, they tend to build for all their citizens’ needs; buses, bikes, and beyond.

-------

I’ve critiqued every word of this meme by now. But one thing I may not have underscored strongly enough yet is that none of this is just about streets. When we talk about how we move through our cities, we’re talking, fundamentally, about our freedoms. Communities of people with mobility impairments know this as acutely as any of us, if not more so.

In a world that’s designed for a very specific kind of body—highly mobile, upright, seeing, hearing, without pain, neurotypical, this unending list of assumed privileges that we may not even realize shapes the design of every structure and street around us—it isn’t hard to empathize with those who have impairments, even if you don’t personally struggle to find accessible parking just to manage a simple trip into town, or love someone who does.

That’s why we need to be generous and wide-reaching in our conversations about transportation. We need to consider not just a narrow range of choices we think are available to us in the way we build our streets—e.g. a parking spot near the restaurant door or one an insurmountable number of blocks away because they put in that damn bike lane—but at the vast choices that we can discover if we think more imaginatively: assistive cycles, a dedicated bus lane, a wide sidewalk in a fine-grained neighborhood designed so you don’t have to walk or cycle an insurmountable number of blocks to the grocery store, on and on.

If we recognize that bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure are often far better economic bets for our cities and safer options for more of our citizens, we owe it to ourselves to think that expansively. We owe it to ourselves to bring everyone along for the ride.