A Town Well Planned: Geographic Form Plans

This article is part of a series in which Strong Towns member and contributor Alexander Dukes proposes a “Civic Development System” whose regulations are split into three core mechanisms: Master Street Plans, Land Use Zoning, and Form Plans. We hope it serves as valuable inspiration when thinking about design options for your own neighborhood.

Read previous articles in this series:

Form codes and plans are relatively new regulatory tools in the civic planning toolbox intended to better control the design of developed land. In regulating the form of land, planners primarily seek to control building heights, footprints, frontage and setbacks. Note that form codes and form plans are not the same thing. A form code defines the terms by which the design of the land will be regulated such as: “the city’s building height limits will divided into three 30, 50, and 70 foot increments.” A form plan applies that form code to specific blocks or parcels, such as: “the city will apply 30 foot height limits along Oak Street, and 50 foot height limits along Spring Street.”

In this article we’ll continue to focus on a form code for the Auburn Mall Site. However; unlike the universal form codes applied to all parcels in the previous article, this article will describe form codes that must be applied with geographic context in a form plan. After describing these geographic form codes, we’ll apply them to the mall site to produce a form plan — the final element of the Civic Development System at the heart of this series.

Listed below are the new form code elements that we will be dealing with in this article:

Auburn Mall Site Form Code (Part 2 of 2)

Building Across Lots – A single main structure may be built across up to three lots. The combined length of these lots’ street frontage on any one side may not exceed 150 feet. Any structure that spans multiple parcels must be built in such a way that the portion of the structure on each parcel may be severed from another portion on an adjoining parcel with no reconstruction of load bearing features.

Main Structure – The primary shelter providing portions of a building including the building’ roofs, which provide direct utility related to the land use function(s) undertaken on the parcel. The “Primary Structures” and “Auxiliary Structures” defined within the previous article are both considered different types of “main structures.”

Main Structure Height Limits – Height limits for the primary structure.

Main Structure Roof Shapes – Gable, hipped, gambrel/arched, mansard, flat, and “shed” roofs are allowed. Up to two gable roof features may be combined with one hip roof shape without requesting a variance. Other allowable roof shapes may be listed by the city, or permitted on an individual basis by the city.

Accessory Structure – Significant aesthetic portions of a building that do not provide direct utility related to the land use function of the main structure on their parcel. Accessory structures include: steeples, pediments, cornices, statues, bell/clock towers, and other forms listed by the city, or permitted on an individual basis by the city.

Only banks, schools (public and private), individually permitted civic institutions, religious institutions, and government facilities are allowed to feature up to two accessory structures by right. Other institutions or individuals may be allowed to construct accessory structures by applying for a variance.

Accessory Structure Height Limits – Height limits for aesthetic portions of a structure.

Primary and Secondary Entrances – Primary entrances of a structure usually (but not always) meet a main boulevard or street. Generally, the primary entrance to a structure will be the same as its “lot front” (described in the previous article). A secondary entrance (colloquially known as a back or side entrance) connects to an alley, or a rear yard on the parcel itself. The city requires at least two entrances for each structure.

Façade Transparency Range (x% thru y%) – The percentage range of a structure’s indicated facade that must be transparent (i.e. a window) at street level for the length of the building’s facade through the vertical dimensions of 2.5 feet and 7 feet from the ground. This regulation does not apply to residential land uses.

Terminating Vista – A structure which serves as a central landmark for residents. A terminating vista is usually tallest building in an area and features aesthetic accessories to differentiate it from the structures surrounding it. Within the Auburn Mall Site, a terminating vista may feature a main structure up to 15 feet taller than its height as defined in the form plan, and include up to two accessory structures.

The Building Across Lots regulation allows a developer to construct a building larger than a single lot, while the city retains existing lot lines. Buildings built across lots must be constructed in such a way that they can be structurally cut into separate buildings along their parcel dimensions. All portions of a building built across a lot must follow all regulations associated with the parcels it sits upon.

The illustration on the right demonstrates how building across lots would work.

The top image shows how developers may build on up to three lots or 150 feet of street frontage. If a developer encounters the three lot limitation before reaching the 150 foot limitation, the building must stop there, and vice versa. Any building that runs across lots must be structurally severable at the “build across lot divisions” indicated by the hashed lines, as demonstrated by the middle image.

The bottom image shows the flexibility build across lot regulations provide developers. Should the owner choose, they can easily sell sections of their building off to other entrepreneurs. This is only possible because the city has required that these structures be severable from the beginning. With a little elbow grease and a relatively small investment to separate HVAC, electric, and water/sewer functions, one building can become three for much less than what it would cost to deconstruct and build anew.

Primary and Secondary Entrances govern the orientation of structures and buildings as it relates to streets and alleys. The form plan will indicate which side(s) a developer will be allowed to use as their primary entrance. A primary entrance of a structure is one that is typically used by the public to enter the building. Secondary entrances are those which the public does not typically use to enter the building, and are intended to accommodate more utilitarian functions.

Primary entrances require unique attention because in certain situations it may be advantageous to the city and landowners for a building to have multiple primary entrances. A great example of this can be found in the southwest corner of the Mall Site’s form plan at the end of this article. In this corner, several parcels are bounded by both a pocket park and a street in this corner of the site. The parcels are allowed to have a primary entrance on more than one side because a retailer like a restaurant might want to serve customers from both sides of their parcel in such a setting.

The Transparency Range regulation is designed to enforce a minimum and maximum amount of transparent features on a building’s façade within the “view zone” of an average person. The intention of these broad regulations is to ensure a comfortable, engaging experience for pedestrians, yet permit a reasonable amount of architectural freedom with respect to the design of buildings. Façade transparency range regulations only apply to the side(s) of a building that features primary entrances.

The illustration on the right describes the how transparency ranges will work.

The diagram at the top of the image demonstrates the relative size of the 50 percent minimum and 80 percent maximum transparency range as applied to a 10 foot tall building façade with a 25 foot wide street frontage. The middle and bottom drawings show a couple different ways a building can satisfy the minimum requirement. It’s easy to imagine the middle building having a traditional brick façade material, while the bottom building could feature a more modern curtain wall.

In the form plan for the Auburn Mall Site, different transparency ranges will be used to taper the visual intimacy of the built environment by allowing a transparency range of 50-80 percent on the edges of the mall site facing major streets, a middle range of 40-60 percent just inside the development, and a lower range of 30-50 percent in the more residential core.

Main Structure Height Limits and Roof Shape regulations control the vertical massing of “main structures” built within the Auburn Mall Site. A main structure provides a direct utility related to the land use function undertaken on the parcel.

The illustration below demonstrates how main structure heights and roof shapes would be regulated:

As shown, structure heights are regulated in 10 foot increments. Ten feet is the total height of a standard story in a building. Of course, buildings may have fewer stories than those illustrated here by featuring higher ceilings, but their total height must remain at or below the height limit described in the form plan for the Auburn Mall Site. Most of the common roof forms found in the United States are shown. Any of these roof forms are freely selectable by right, and shouldn’t overpower the overall visual cohesion of the urban environment. More unique roof forms like domes, cones, or butterfly roofs would require approval from the city.

Also note that 10 foot basements are allowed for every structure. Because the parcels within the Auburn Mall Site are so small, the city should afford landowners the maximum opportunity to reap value from their land.

Regulations for Accessory Structure Heights control how tall “accessory structures” are allowed to be. Accessory structures are significant aesthetic portions of a building that do not provide direct utility related to the land use function undertaken on the parcel.

The illustration below shows a variety of accessory structures with their height limits:

Generally, accessory structures may only be featured on buildings whose use is at least partially that of a bank, school (public or private), permitted civic institution, religious institution, or government facility. This restriction is intended to limit accessory structures to organizations that are important to the community. If every landowner had the right to erect a statue, giant flag, or steeple, the skyline would quickly become cluttered with too many focal points. Therefore, the tallest and most prominent structures in the community should be reserved for those entities that the community cares about.

One exception exists to the limits on accessory structure features: Any building on a parcel defined as a “terminating vista” is allowed to feature up to two accessory structures, regardless of the use of the building.

Terminating Vistas are structures at a major intersection or end of a street that are typically composed of a main building and at least one accessory structure. Because they tend to be so prominent and adjacent to well trafficked areas, terminating vistas serve as orienting landmarks that define a place and a community’s brand.

We’ve all had the experience of going to a new place and having a resident tell us to “meet by the clock tower” or ask “do you see the water fountain?” Such helpful landmarks tend to be designed into areas to help give the place an overall sense of visual cohesion that is hard to achieve without some intentionality. Pursuant to this, the form plan for the Auburn Mall Site permits developers to construct four terminating vistas within the site.

Some great examples of terminating vistas that have been designed into places are shown below.

The Form Plan

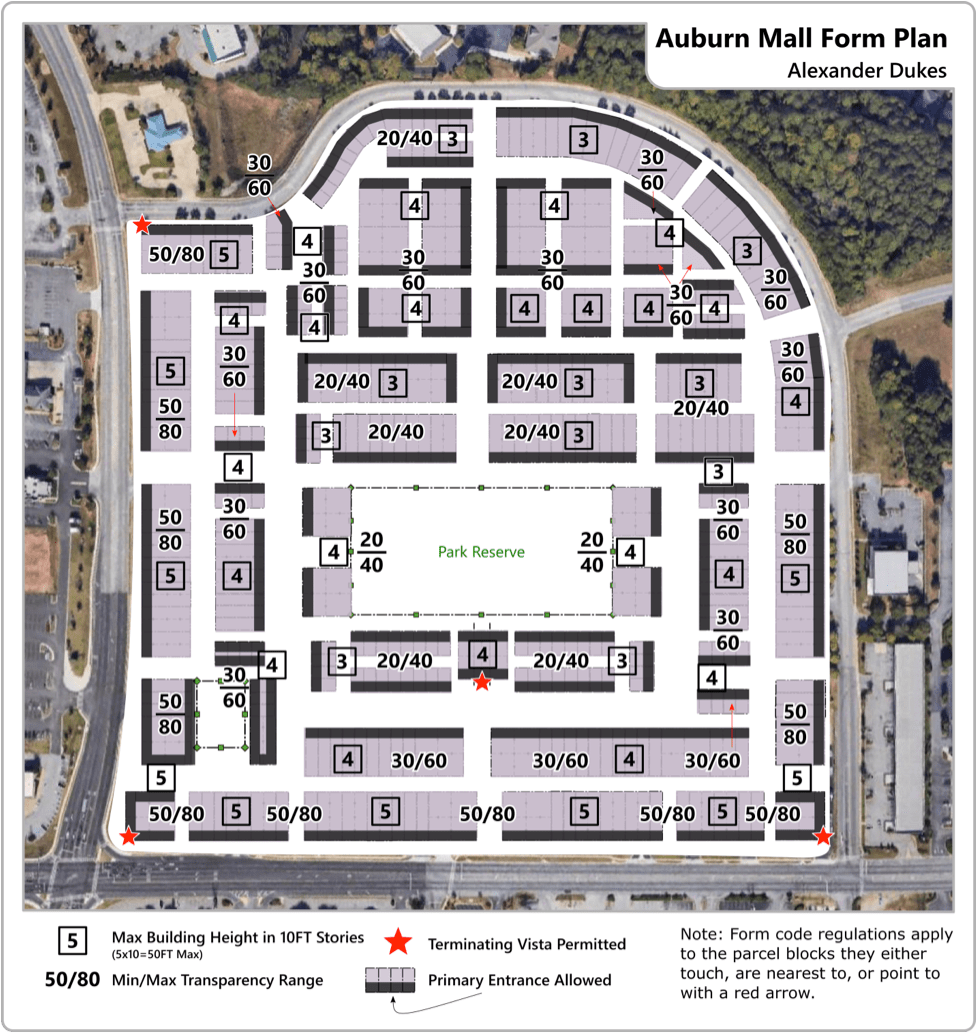

Finally, here’s where all of the regulatory tools we’ve been discussing throughout this article come together. This is what a form plan looks like when we apply our four major form codes with geographic context to the Auburn Mall Site:

As you can see each block of parcels has been given a maximum structure height, a transparency range, and an allowance for its building’s primary entrance. Four parcels are granted the privilege of using accessory structures to create terminating vistas for the community.

While the plethora of numbers on this plan may seem overwhelming, a couple of tips regarding these types of plans should help users better understand:

- First, think of the symbols in the form plan as pieces on a board game. Any purple block of parcels a piece touches and/or is directly adjacent to receives the regulations expressed by that “piece.”

- Second, there are only three tiers of structure height and transparency range regulations in the form plan. So any time you see a 30/60 or 4 in the plan, know that these are simply the middle tiers for transparency and building height in the plan. Anything higher or lower than these numbers is either the maximum or the minimum extent of that regulatory element.

Digging into the plan itself, I tried to taper the building heights and transparency ranges from their maximums on Opelika Road and University Drive to their minimums within the core of the neighborhood. Back in the zoning plan articles, I emphasized my preference for the exterior of the site to take full advantage of the economic dynamism that is bound to occur along the two major thoroughfares and their intersection, while the interior of the site should encourage a quieter, more domestic atmosphere.

To support this objective, the tallest and most transparent buildings are located where the most valuable land is — right off Opelika and University. Building heights and transparencies then scale down within the second ring of blocks within the Mall Site to foster an urban environment with greater privacy and less imposition. Finally, the third ring around the park affords maximum privacy to residences and encourages the establishment smaller specialty shops intended to serve customers who frequent the area enough to relax and enjoy their more unique offerings.

---

Hopefully through my work on this series over these many months I have provided you with at least some ideas on how we can better encourage more economically productive, cohesive, and engaging land development in our communities. I continue to believe that it will be difficult to achieve those goals without systemic change to the way we regulate land development in our cities.

From the individual citizen to the federal bureaucrat, we need to start having a fundamentally different conversation about how we build our shared living spaces. Whether or not you believe the Civic Development System I’ve described with the “A Town Well Planned Series” is viable or not (let me know in the comments!), I hope this series has at least started a conversation about the way we regulate land development in our communities. Thanks for reading!

(All graphics created by and courtesy of Alexander Dukes.)

Alexander Dukes (Twitter | LinkedIn) has been a regular contributor for Strong Towns since 2016, and works as a Community Planner for the US Air Force in California. He is a graduate of Tuskegee University and Auburn University, with a Bachelor’s in Political Science and Master’s degrees in Community Planning and Public Administration. With this background, Alexander focuses his planning work on public policy and urban design for both military and civilian applications. Alexander's goal is to build sustainable human environments that provide all citizens with access to cohesive communities, affordable housing, meaningful employment, and beautiful places.