Can Austin Keep Streets Weird (and Safe)?

Strong Towns member Heyden Black Walker together with colleague Jay Blazek Crossley are sharing today's guest article about their hometown of Austin, TX and their fight to make it a safer, more people-oriented place.

In Austin, Texas we have a perfect storm brewing. We all know there is a growing challenge to keep Austin weird when our artists, musicians, and neighbors are being priced out of the city; with the high cost of limited housing, many are forced to move further out, significantly increasing already high transportation costs and travel distances. The city's current plans call for adding housing with multimodal transportation choices along our urban corridors, transforming them into areas suitable for the complex environment of streets where people can live, work, and play. Once intended solely for cars, these places could begin to support healthy human interaction and serve everyone.

We want to make it through this storm stronger with a new understanding of what we expect out of these corridors. Design options are currently under consideration, giving residents the chance to really define our twenty-first century transportation networks. But with these future plans on the line, there's also a risk that the standard practice of prioritizing fast vehicle movement will take precedence again.

Our Core Values

Previous public input processes established core values for our corridors, stated in the form of a Contract with Voters and adopted by our city council. We have a clear vision for:

…making corridors livable, walkable, safe, and transit-supportive, and aligned with the principles and metrics in the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan, with goals of reducing vehicle miles traveled, increasing transit ridership and non-vehicular trips, and promoting healthy, equitable, and complete communities as growth occurs on these corridors.

Yet in the on-going public input process, it has become apparent that underlying engineering standards, if allowed to supersede these stated community values, will dictate designs that maintain the status quo of fast-moving, car-oriented streets instead of slow, people-oriented streets.

Our urgency to modernize our standards is driven, in no small part, by the fact that voters approved $482 million in a 2016 bond vote specifically to focus on completely rebuilding nine of these urban corridors by 2024, including a TxDOT arterial called State Highway Loop 275, known as North Lamar for those that live there. If we can get this right, it will be an important precedent for cities and states all over the country.

Fast-Moving Corridors in a Growing Region

Our corridors are poster children for the stroad. We ask them to move high volumes of traffic at high speeds of 40 + mph (a road), while loading them up with traffic lights, frequent curb cuts, disconnected sidewalk segments, strip shopping centers and parking lots.

These corridors were designed to move cars as Austin doubled in population every 20 years. Once a medium sized city surrounded by the Texas Hill Country, today Austin is the 11th largest city in the country and the urbanized Austin Round Rock Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) covers 4,286 square miles (3.5 times the size of Rhode Island). We have spread ourselves out over a vast area, straining our transportation systems.

To make things even more complicated, many of these corridors are still owned and operated by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) which focuses on building highways for cars, not streets for people. TxDOT is in a different stage of its own shift from twentieth century car-dependency policies to becoming a comprehensive steward of safe, multimodal networks. Texas State Highway Safety Plan Emphasis Area Teams are, right now, working on action plans to deploy countermeasures that include design speed, pedestrian safety, safe crossings, and other crucial urban transportation reforms. But TxDOT does not seem quite ready to rebuild these former state highways into the urban multimodal corridors that Austin envisions.

A lack of safe — or any — walking facilities on North Lamar Blvd forces people to walk in the ditch. (Source: Heyden Walker)

Redesigning Corridors

While working to meet the relatively short-term (8-year) goals of the bond, we are also fighting over a multi-year, multi-million dollar rewrite of our Land Development Code, CodeNEXT. There is general agreement that our largest land use issues are housing and transportation inequity, but reaching a solution for those problems has proven extremely contentious.

CodeNEXT envisions adding the missing middle housing we have prohibited over the last 30 years with our existing code, calling for hundreds of thousands of new housing units along these corridors.

At the same time our transit agency, Capital Metro, just redesigned their network, and is working toward an ambitious transit vote for 2020, with a regional transit vision that could include high capacity transit on many of these corridors. And the Austin Transportation Department is working on a new Austin Strategic Mobility Plan that includes the opportunity to rethink the city’s right of way prioritization policies to better allocate space for bus and future rail provided by Cap Metro. Yet there is a strong backlash from bureaucrats and some elected officials to maintain our twentieth century experiment in car-priority lanes. Which is why it feels like a storm brewing.

Click to view larger. (Map by: Farm&City. Data source: TXDOT CRIS Database.)

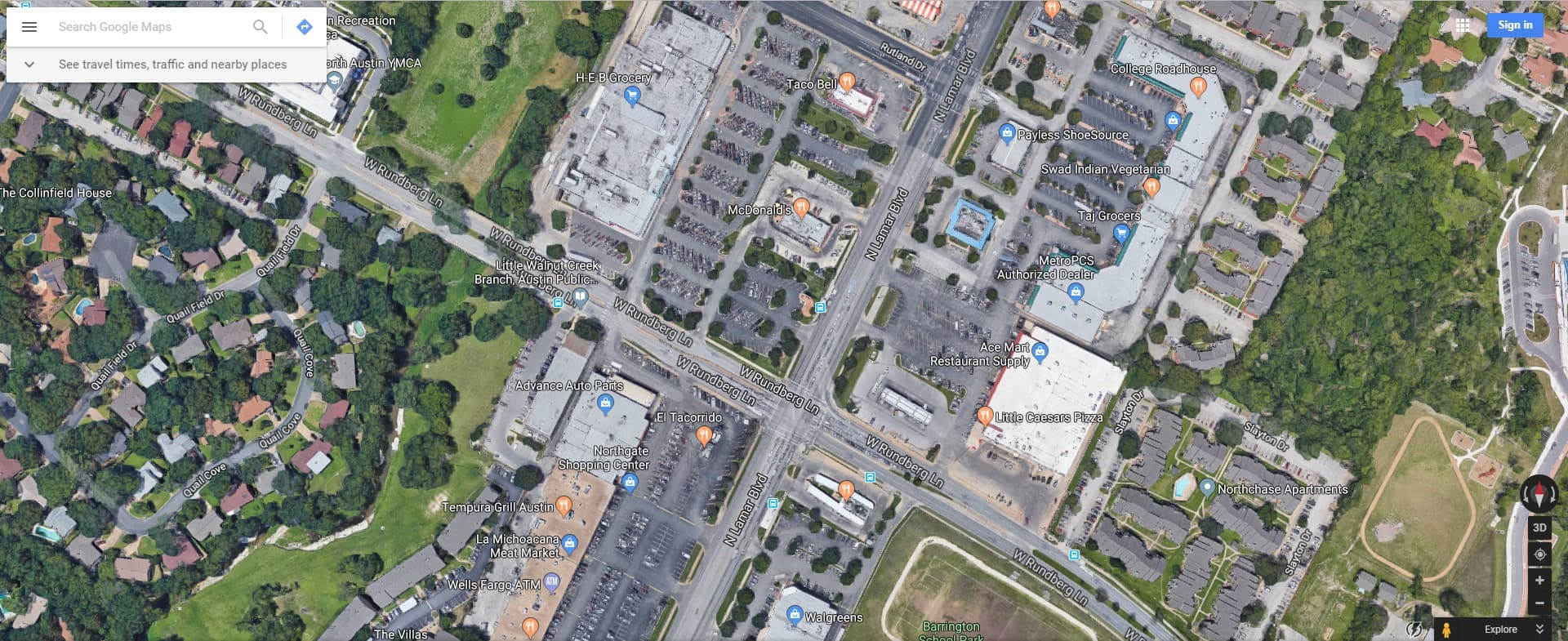

North Lamar Boulevard

To better understand these tensions, let’s take a closer look at North Lamar. One of the nine corridors identified in the City’s recently released Proposed Corridor Construction Plan, North Lamar has astounding room to change and provide a rapidly growing area with a walkable urban core.

North Lamar’s neighborhoods provide much of Austin’s workforce housing, with more residents per square mile than anywhere outside of downtown. Many people who live here walk to buses, both local and frequent rapid service.

TxDOT controls North Lamar, which has, over time, morphed from state highway to stroad as the region grew up around it. Under TxDOT’s stewardship, the right-of-way has seen little significant change or improvement: drainage “bar” ditches line the sides, beaten paths clearly indicate the need for sidewalks (see image above), and people drive at dangerous speeds. Austin wants to improve it.

Like most stroads, North Lamar is a very dangerous place for people. In the last 7 years, 15 people have died on this 6-mile stretch, and 64 people have suffered incapacitating, life-altering injuries. People walking or using wheelchairs account for an astounding 62% of traffic deaths along this section of North Lamar.

One of those 15 people was a man named Donald Norton, who was crossing North Lamar in a motorized wheelchair. The police report notes that he was “crossing the roadway where there was no crosswalk or intersection.” The same report fails to note there is no continuous sidewalk network available for Mr. Norton to get to a crosswalk (motorized wheelchairs are not made to navigate drainage ditches).

The corridor bond money could be used to honor Mr. Norton and the many others who died or suffered incapacitating injuries along North Lamar with a new design that prevents more families from suffering as they have.

When stroads in urban areas no longer look and feel like highways, they can become safe streets. One example is Queens Boulevard in New York City where design changes made the road safer and more functional for all users. Once known locally as the “Boulevard of Death” this road today is considerably safer. A recent New York Times article reports, “Not a single pedestrian or cyclist has been killed on the seven-mile long thoroughfare that slices through Queens since 2014.” Our own boulevard of death could benefit from this precedent.

Bond construction plans include protected bike lanes and sidewalks, continuous and compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). But does our proposed construction plan truly make these corridors safe for everyone traveling them today and in the future?

Designed for Speed

While adding sidewalks, bike lanes and safer crossings will significantly improve this corridor, it looks like underlying engineering standards that have proven unsafe for people are still being used.

Five lanes of traffic, large parking lots and setbacks contribute to the race-track ambience. There is nothing easy, comfortable or safe about walking across this stroad, a sad example of what Chuck Marohn talked about in his Gross Negligence webcast earlier this month.

North Lamar’s car lanes are 13 feet wide (highway sized), with a continuous turning lane and pedestrian areas kept clear of “hard target” obstructions (“clear zones”) so that cars have a safe place to recover when they run off the road.

These forgiving design features tell people this is an area where cars go fast (and they do). They also make these stroads extra dangerous for people — even those in their cars. Clear zones for errant vehicles are a design standard set out in TxDOT’s Roadway Design Manual (RDM). People walking along this roadway are considered “soft targets” in this system of designing streets.

In recent public meetings, the TxDOT engineer for North Lamar has stated that clear zones are required by the RDM for North Lamar. He specifically quoted RDM standards to legitimize resistance to modern urban street designs. This thinking discourages things like street trees, which provide shade on hot Texas days, clean the air polluted by thousands of cars and provide a safety barrier between cars and people. It is hard to reconcile the vision of a parent walking with their child along a sidewalk placed intentionally in a clear zone.

Another contributor to the safety of people using this corridor is the speed of vehicles. We must remember the core values set out in the Contract with Voters. The City of Austin has had well-documented successes in right-sizing streets to improve both safety and transportation efficiency. This work should guide plans to wrangle these stroads into streets for people.

The design speed of these corridors can and should prioritize safety for people. Per the engineering team, those design speeds are currently set at 40 mph. When hit at 40 mph, 9 out of 10 people will die. 40 mph is not a safe speed for a multimodal, complex corridor. The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) states that urban arterials should have a target design speed of 35 mph or less, explained in this easy to understand guidance. As in the example of Queens Boulevard, multiple techniques can be used to create a safe environment for everyone using the street.

Should we decide to continue designing a corridor made for driving through this neighborhood at dangerous speeds, we will not achieve our goal of building healthy, mixed-use, mixed-income urban places suitable for Austin’s twenty first century.

Corridors of the Future

Adding people, housing, jobs, retail, and all the elements necessary to build complete communities on our corridors is consistent with the vision we set out when we agreed to spend almost half a billion dollars. The work we do in the short term sets us up for success in our long-term planning. It is critical that this work be guided by our shared value statement.

As community advocates we are pushing back against these long ingrained engineering standards. The work can often feel inspiring and hopeful, but sometimes we wonder if the many consultants and overlapping jurisdictions involved really have the fortitude to #slowthecars enough to convert these stroads to streets. Austin is fortunate to have the funding and political will to make these important changes to our most egregious stroads. So, we’ll see… maybe something really special is brewing and we’ll be able to keep Austin weird.

(Top photo source: Tendenci)

About the authors

Heyden Black Walker, CNU-A, is an urban planner, former teacher, and mother of two young adults in Austin, Texas. She co-founded Reconnect Austin, a community-based call to lower and cover the main lanes of I-35, creating a vision for a multimodal corridor that reconnects communities. Heyden holds a Masters in Community in Regional Planning from UT-Austin and serves on the City of Austin Pedestrian Advisory Council, Multimodal Community Advisory Committee, Bond Corridor Focus Group; the Congress for the New Urbanism; VisionZeroATX; and Walk Austin. Heyden is a 2016 Fellow of the national Walk College.

Jay Blazek Crossley is Executive Director of Farm&City, a charitable nonprofit think tank dedicated to high quality urban and rural human habitat in Texas in perpetuity. He holds a Masters in Public Affairs from UT-Austin and serves on the board of Vision Zero ATX, the City of Austin Multimodal Community Advisory Committee and several Texas Strategic Highway Safety Plan Emphasis Area teams.

Amy Emery is a community leader focused on fostering sustainable growth and smart development in Warrenville, Illinois. She joins Norm to discuss several ways the city is working to build a core downtown. (Transcript included.)