Think Big, Work Small

Jason Segedy is a Strong Towns member and the Director of Planning and Urban Development for the City of Akron, Ohio. The follow essay is a shortened version of a post from his blog, Notes from the Underground. Follow all our coverage of Akron here.

Akron, Ohio is a city in flux. Once the center of the global rubber and tire industry, Akron hit its peak population in 1960, expanding to 290,000 residents. Since 1960, the city has lost 31% of its population. Today it is home to just 198,000 residents.

Despite its significant loss of population and manufacturing jobs, though, it is inaccurate to pigeonhole Akron as a “disappearing Rust Belt city”. The fact that the city once contained the corporate headquarters of at least half-a-dozen Fortune 500 companies, and all of the wealth that they generated; and the fact that it has since diversified its economy, retaining and attracting new high-paying jobs, means that it is still home to some of the most stable and affluent urban neighborhoods in the entire Great Lakes region. It should not be painted with an overly broad brush.

If we want to prepare this city for an economically resilient future, we must focus on restoring housing, attracting new residents, strengthening neighborhoods and taking the small but powerful steps to make Akron a strong town.

It's Time to get Housing Back on Track

Today, when it comes to housing, Akron is a city of contrasts. It is not one real estate market, but half a dozen. Approximately one-quarter of the city’s housing is in great shape, while another one-quarter is extremely distressed. The remaining 50% could be characterized as being at a tipping-point of sorts — largely solid, older homes, in middle class neighborhoods — for now.

The city contains approximately 96,000 housing units. The median housing unit (houses and apartments) was built in 1952. 64% of them were built prior to 1960. More housing was built during the Great Depression than has been built since 2000.

When you look at the housing on Akron’s near-west side, for example, you can see the radial pattern of the pre-1920 homes that were built along the former streetcar lines. You can also see the way that adjacent neighborhoods evolved and filled in between 1920 and 1960, along with scattered pockets of more recent infill development. You can also see, on the bottom right, a downtown where very few people currently live.

This map of housing in Akron and its inner ring suburbs illustrates the radial streetcar pattern even better – neighborhoods with the highest percentage (88%+) of housing built before 1960 are the darkest red, while those with the lowest (less than 12%) are the darkest blue.

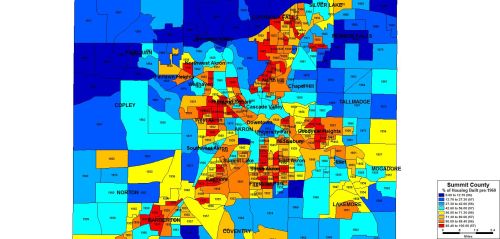

Akron (from akros - Greek, for “high place”) is a city of hills that was home to an incredibly dirty industry. The wealthy moved northwest — uphill and upwind of the pollution. That pattern holds to this day; the neighborhoods with the highest median house prices (over $120,000) are in dark red, the lowest (under $57,000) are in dark blue.

A similar pattern holds for annual median household income; the neighborhoods in dark red have a median household income of $54,000 or more and those in dark blue have a median household income of less than $18,000.

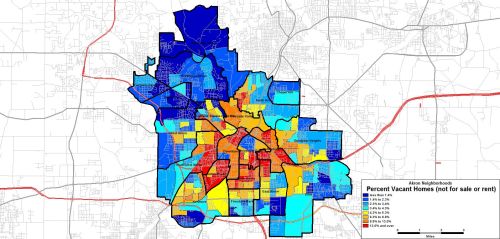

Approximately 6% of the city’s housing is vacant (and not for sale or rent). Vacancy is not evenly distributed. In the darkest red neighborhoods, over 13% of the homes are vacant; in the darkest blue, less than 1.4% are.

We, at the city government, are presently hard at work crafting a housing strategy that reflects today’s reality — that of a city that contains thousands of solid, beautiful, well-maintained historic homes, and that of a city that has torn down 2,100 abandoned houses in the past five years.

We are committed to pursuing a growth strategy in Akron — one that looks at reality with both eyes wide open, and that employs time-honored urban design principles and innovative placemaking strategies to build on our considerable strengths, and to turn our liabilities into assets.

It's Time to Bring the People Back to Akron

We are reinventing Akron as a place to not simply work, or play, but to live. Our long-term goal is to grow back to 250,000 residents by 2050, and our short-term goal is to get our current population of 198,000 back over 200,000 by 2020.

I don’t believe that a “Shrinking Cities” model of mothballing infrastructure and relocating residents will work for us. Instead of putting precious time, energy, and money into shrinking, let’s build on our neighborhood assets and figure out how to grow again.

Why does it matter if we keep losing population? Because the size of our population has incredibly important ramifications for our tax base; our employment base; the performance of our schools; the distribution of everyday amenities like grocery stores, shops, and restaurants; the delivery of public services; and less tangible, but equally important things like our sense of place and our sense of ourselves. Here’s how population impacts three key aspects of our city life:

- Fiscal: We will have the same amount of infrastructure to maintain and the same level of public services to provide, whether we grow or shrink. Permanent contraction of our population means the same amount of services to pay for, with less people to help share the cost of paying for them.

- Equity: As our neighborhoods are abandoned, decline, and become hollowed out, access to social and economic opportunities diminishes along with the population. The jobs disappear, the doctor’s offices disappear, the grocery stores disappear – relocated, often, to a distant and increasingly inaccessible locale. The sandwich cafe, hardware store, or barbershop that used to be a short walk around the corner is now a 45-minute bus ride away.

- Social: This is the intangible, but critically important issue of sense of place. As our once-vibrant neighborhoods and commercial districts become mouths full of missing teeth, our residents’ sense of place and sense of self is correspondingly diminished.

Akron was recently ranked as the most affordable housing market of the 100 largest metropolitan areas. The good news is that it is an inexpensive place to live. The bad news is that the low cost of housing makes it extremely difficult to cost-effectively rehabilitate many houses in most neighborhoods.

In many of the city’s most distressed neighborhoods, a house can easily be had for $20,000 or less. However, even after an investment of $60,000 or more to rehabilitate it, the owner may still only be able to sell it for $40,000. It is a difficult market proposition.

The Strategic Housing Plan that city leaders are working on recognizes our current reality — that of a stagnant housing market where new construction has been minimal, where it is difficult to cost-effectively rehabilitate homes, and where much of our urban fabric is being eroded by demolition. The Plan will examine three questions: What do we have? What do we need? How do we get there?

The last question is the most important and most complicated one to answer. We will need half-a-dozen (or more) different redevelopment strategies for our neighborhoods depending on which neighborhood we are talking about. We are reaching out to developers, home builders, and realtors to figure out how to strategically, intentionally, and creatively rebuild each one of our neighborhoods. Doing this well will require public, philanthropic, non-profit, and private sector leadership; in partnership with everyday people working together, one block at a time, one neighborhood at a time, to rebuild and transform their community.

No matter how great this city is to live in (and it is), we can’t grow again if we don’t figure out how to build and rehabilitate more housing than we tear down. It’s simple arithmetic. Right now, we have an oversupply of houses that people don’t want, and an undersupply of houses and apartments that people do want.

The time is right to take a fresh look at both supply and demand. The market has begun to change, especially downtown, as millennials, empty-nesters, and others interested in urban living, are demanding new multi-family housing.

There is also an untapped market for rehabilitating historic homes in many of our neighborhoods. The challenge is to learn how to make that happen in a cost-effective manner. The opportunity is the revitalization of the numerous high-quality, historic, irreplaceable neighborhoods throughout our community that can serve new generations of Akronites for the next 100 years.

It's Time to Strengthen Akron's Neighborhoods

As we rebuild Akron, it is important that we avoid false choices – neighborhoods versus downtown; commercial development versus residential development; people versus jobs. The answer to these questions is not a multiple-choice “either/or,” it is an “all of the above”.

We need to make our downtown more like a neighborhood, with thousands more people living in it.

Downtown currently has a 23% commercial vacancy rate, as many law offices, accountants, and other professional services have relocated to the suburbs. We can turn that current liability into an asset, through adaptive residential reuse of commercial buildings, as places to live.

As is the case for most cities in the Great Lakes region, downtown Akron is full of irreplaceable and high-quality historic architecture.

And, like most cities in our region, we did terrible things to our downtown through urban renewal.

We will be reforming our zoning code to adopt form-based overlays to encourage the type of mixed-use, walkable development that originally made our downtown so successful as a place to live, work, and play.

Conversely, we need to make our neighborhoods more like a downtown, with revitalized, walkable, mixed-use business districts. Neighborhood development is economic development.

The old Akron that remembers being the Rubber Capital of the World is fading away. A new Akron, with different memories and different needs is being built — looking forward, but standing on the shoulders of giants.

It's Time to Think Big, but Work Small

The key to rebuilding our community is to think big, but to work equally hard on doing the small things extremely well.

American cities have often gone astray, looking for that mega-project or that silver bullet. The urban renewal of the 1960s brought us expensive freeway projects like the Innerbelt, and cold, foreboding civic spaces like the original incarnation of Cascade Plaza. More recently, cities have placed their faith in stadiums, convention centers, and casinos. Few of these projects have delivered the civic benefits that they originally promised. It is not that these things are unimportant — they can be great things, and they may well be necessary — but they are insufficient. A sledgehammer is a valuable tool, but not if you are trying to repair a watch.

Does this mean that we should never do or dream anything big? Of course not. But we must be prudent, patient, and wise. Our cities are far more akin to living organisms than they are to machines. Given that reality, we must tailor our approach to fixing (healing) them, accordingly.

I believe that the way forward is to put people and places first. Big plans are important, but so are little plans. Because they often involve fundamentals, they are easier to pull-off and more readily establish trust, inspire hope, and build relationships. Trust, hope, and relationships are the indispensable ingredients necessary for doing bigger things further down the road. Without them, we labor in vain.

The end that we are seeking to achieve is the creation of wonderful places for the wonderful people that live in our city. May we all arrive at that end – working together.

(Top photo source:Tim Fitzwater via Akronstock)