Best of 2018: Stop Playing Public Hearing Bingo

We’re continuing our run of some of our best and most popular content of 2018 with this piece by longtime Strong Towns member and regular contributor Sarah Kobos.

Strong Towns is unlike most advocacy organizations in our space, in that our membership includes a very broad spectrum of dedicated #StrongCitizens and local community advocates who are working in their own ways to make their own places better. We don’t only speak to professionals such as architects, planners, and engineers.

Perhaps no writer on our site does a more eloquent job of speaking to the Strong Citizens in our audience than Sarah Kobos. She has a brilliant way of both laying out, in plain English, the stakes of things we might not always give that much thought to (like subdivision regulations and vehicle Level of Service), and also giving community advocates the tools and advice they need to strengthen their arguments and make real change.

This piece, “Stop Playing Public Hearing Bingo,” was one of her most popular pieces ever, and we’re glad to give it a well-deserved encore here at the end of 2018.

If you’re a civic-minded nerd like me, you’ve probably been to a lot of public meetings: planning commission meetings, city council meetings, advisory board meetings, board of adjustment meetings, neighborhood meetings, town hall meetings...

Every public hearing seems to be filled with the same sorts of people making the same tired arguments. (Source: Micheal Kappel)

After a while, you start to notice a pattern. The archetypal players in a public meeting are as predictable as the characters in a Hollywood rom-com. There’s the Long-term Resident Opposed to Change; the Humble Businessman Just Trying To Make a Living; the Passionate Neighborhood Activist; the Developer Who Has Already Bent Over Backwards; the Developer’s Buddy Who Thinks It’s a Great Idea; the Historic Preservationist Fighting To Avoid Catastrophe/Incompatible Design; and a Guy Who Bicycled Here.

No wonder the city officials in attendance appear to be deeply contemplating the state of their cuticles. Every meeting is different—and yet every meeting is the same. Like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, you can predict what everyone’s going to say before they even step up to the mic.

So let’s break that worn-out mold. Here are a few ideas to make you a more effective—and more interesting—public hearing participant.

1. Stop Playing Public Hearing Bingo

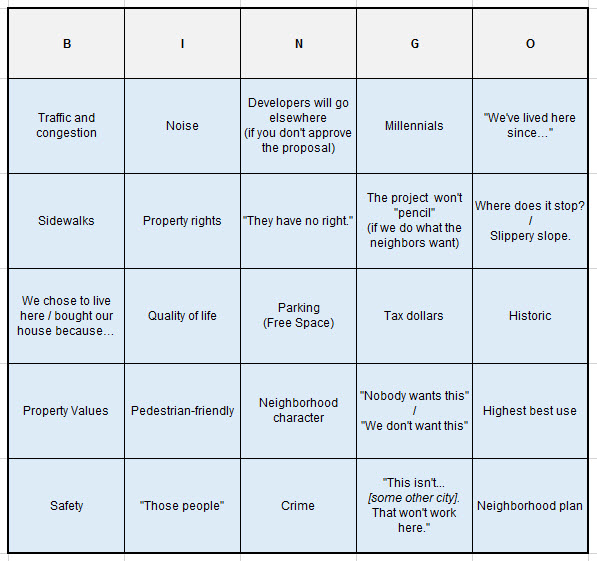

I'm starting to believe that there's a random argument generator at City Hall that allows people to pick from one of seven options. Every opponent of every plan argues that the dreaded proposal will destroy property values, create parking problems, and increase traffic, noise and crime. Every supporter of every plan claims that their proposal will generate jobs and tax revenue, while attracting young professionals to the community—and failure to approve it will have a chilling effect on business. What each side lacks in data and actual facts, they make up for in supreme confidence in their own opinions.

The first step to being a better advocate is to stop making those arguments. You can always pass the time by playing a little Public Hearing Bingo, but don’t fall into these tiresome tropes yourself.

Public Hearing Bingo by Sarah Kobos

2. Gather Facts and Information

The nice thing about a Strong Towns argument is that it’s fact-based. You can actually support your statements with data. So before your next public meeting, do some analysis. Land use proposals should answer the question: “Is the development fiscally sustainable and will it improve the short- and long-term financial condition of the city?”

If you’re lucky enough to live in a town like Fate, TX, local officials are already asking these types of questions. If not, do some research of your own.

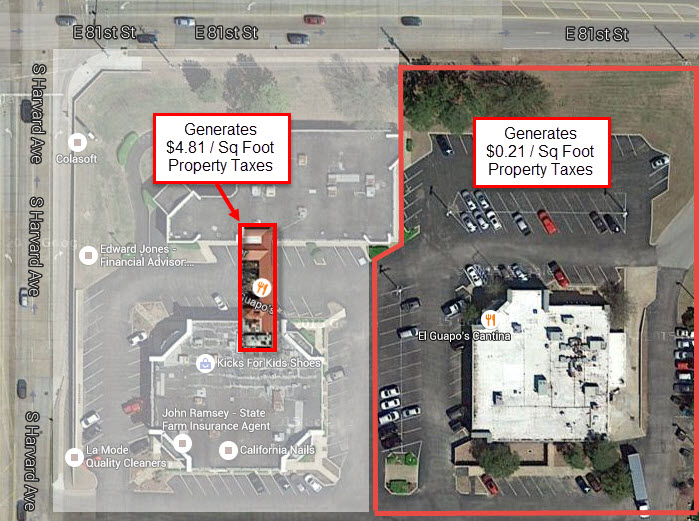

A good place to start is with local tax assessment data, which is often available online. If not, you’ll need to make a trip to the Assessor’s office to view property information. Use the tax assessor’s database to find details of a particular property: market value, annual taxes paid, square footage of the lot, building size, previous sales price, number of stories, type of construction, year built, current and previous owners, etc.

It seems like a lot of money, until you divide it by total square feet. This property is only generating 30.6 cents per SF, and revenues are declining. (Source: Tulsa County Assessor data.)

Gather information for the property in its “current state,” and then see if you can gather information for a property that is similar to that being proposed. (As real estate has become more and more commodified, it’s usually easy to find comparable projects because developers tend to mass produce a certain type of “product.”)

Data on sales tax is harder to find because it's considered confidential. Businesses simply don't want people knowing their business. Still, there are ways to extrapolate data and make rough estimates. One tool is to use regional average sales per square foot for various types of retail establishments. This may help you calculate a ballpark number.

Side note: New developments don't necessarily "add" sales tax. We're all buying our shampoo somewhere. Our budget for eating out doesn't change based on the number of restaurants in a city. We may shift our purchases, but we don't always increase how much we spend. Unless you're drawing customers from outside your town, or attracting new residents, you're probably not adding all that much sales tax.

Next, you can use Google Maps in satellite view to obtain fairly accurate measurements of street widths, and the length of adjacent right-of-way. (Zoom in, click on a location, right-click and select “Measure Distance,” then click on another point to see the distance between the two.)

Contact your town’s Public Works/Streets Department to obtain information about the maintenance and replacement cost of various types of public infrastructure. Study the development proposal to see if additional public infrastructure investment is being requested. Look for requests like designated turn lanes, road widening, new signalized intersections, etc. Try to understand the short and long-term costs associated with these amenities.

3. Use Graphics to Make Your Case

Architects and developers know that there’s nothing like a sexy, full-color rendering to get people excited about a proposal. Sometimes, it's better to show than to tell. So use the power of graphics to help make your case.

You don't need fancy software to make compelling graphics.

Here’s an example that I used to show the benefits of the traditional building pattern by comparing two restaurants. One resides in a traditional two-story downtown building (with a lovely rooftop patio), and the other is a typical auto-oriented, single-story building surrounded by parking. In this graphic, I’ve superimposed the downtown building onto the suburban shopping center to compare the two properties.

And here’s another example of how this very modest but productive downtown building exists on the same amount of land needed to park 11 cars.

You don't need fancy design software to tell your story visually. In the examples above, I used an inexpensive screen grabber called Snagit to capture and manipulate images from Google Maps. I won't win any prizes for graphic design, but these images tell a compelling story better than words ever could.

You can also use Excel to create professional looking charts and graphs.

Sometimes a picture really is worth a thousand words. So bring a few graphics with you to the public hearing.

4. Don’t Babble

There’s something about a microphone that makes people ramble. Whatever it is, resist the urge. Just because you have five minutes doesn’t mean you have five minutes worth of things to say.

Be clear and succinct. It will strengthen your argument. Plus, you’re more likely to be heard if you don’t exhaust your audience. Another benefit: public officials will appreciate you for respecting their time. Write down the major points you need to make and use your notes to keep yourself on track. Keep your tone friendly and your arguments rational and to the point.

5. Arguments Aren’t Won During Public Hearings

Having said all this, it probably won’t matter.

I used to believe that if you did your homework, showed up with facts, and made a strong, logical argument, it would influence the outcome of a public hearing. Oh, the idealism of youth...

Public meetings get everyone “on the record,” but your 3-5 minutes at the microphone are unlikely to change the outcome. (Photo by Michael Kappel)

As it turns out, public meetings are often little more than “democracy theater,” designed to make everyone feel good about following a process and “hearing” from constituents. By the time you reach the public hearing phase of the game, it’s too late. The real decisions have already made, during private meetings and preliminary work sessions where elected/appointed officials, city staff and various players hash out the details. Public meetings get everyone “on the record,” but your 3-5 minutes at the microphone are unlikely to change the outcome.

Why bother? Because there’s no need to go down without a fight, and because sometimes—amazingly— it does work. Perhaps a sympathetic official just needs political cover to do the right thing. Or maybe the members of an oversight committee actually have open minds. Or a small miracle occurs and the swing vote is moved by your argument. You never know, so it’s always worth a try.

More importantly, if you care about your city, you’re playing the long game—and you never know who’s in the room. If you make a powerful argument supported by data, and present it thoughtfully and respectfully, people in the audience will listen. New thoughts will occur. Wheels will start turning. Perspectives may change. Over time, you may be surprised to discover you’re not alone.

Remember, the best argument is the one you don’t have to make because someone else just made it for you. If you lose a vote but gain an ally, it's still a win.

6. Build Relationships

This is where the real work takes place. Not during those brief moments in front of a microphone, but during face-to-face meetings with elected officials and citizen appointees.

Old-fashioned meetings will give you time to have a real discussion: to speak, listen and learn from each other. They provide a chance to find common ground and understand each other’s perspective. They help you get to know people as human beings, not caricatures, which is a much better foundation for a good working relationship moving forward.

Don’t be intimidated to reach out to public officials. They deserve to hear your side of the debate, because they are certainly hearing from others. And as more and more people consider the logic of the Strong Towns philosophy, you never know what can happen

Stanis Moody Roberts is a business owner from Portland, Maine, who has been organizing local opposition to a highway expansion for the past year. He joins today’s episode to discuss this journey and the progress his community has made.