Methodist Urbanism: Ocean Grove

Johnny Sanphillippo is a Strong Towns founding member who blogs at Granola Shotgun about how we inhabit the landscape and how places grow, change, and decline or persist over time. We love his photo tours of idiosyncratic places that have universal lessons to teach us. Here’s a new one, republished from his blog with permission.

Here’s the ubiquitous American landscape with a dash of central New Jersey local color. It’s not the rain and dark skies that make it look so bleak. No amount of sunshine can brighten this much asphalt, synthetic stucco, and vinyl siding. There’s no point in complaining about any of it. It exists and will continue to do so for the duration. Shrug.

But pass through a set of columns and enter a little Victorian-era town trapped in amber that reminds us that we used to build better places. Ocean Grove was established as a Methodist revival summer camp in 1869. In the aftermath of the Civil War, people were hungry for faith, fellowship, and order. The (then) remote seashore location offered fresh air, tranquility, and escape from the smokestacks, heat, congestion, and disease of industrial cities like New York and Philadelphia.

The street grid was measured out and small lots were leased with 99 year terms to members of the church. The town began with tents pitched on simple wooden platforms. There were 200 tents for every solid home in the early years. Religious services were held in larger tents and tabernacles. 114 tents still remain in use after a century and a half and are inhabited from May to September each year.

Over time, cabins were added to the back of each tent to provide sanitary facilities and kitchenettes. At the end of the season, the tents are folded away inside the cabins. Because the people who choose to live here are all self selecting members of the same community with common sensibilities, the tent city is remarkably safe, clean, and well maintained. People come to Ocean Grove intentionally to be together. That’s the whole point of the town.

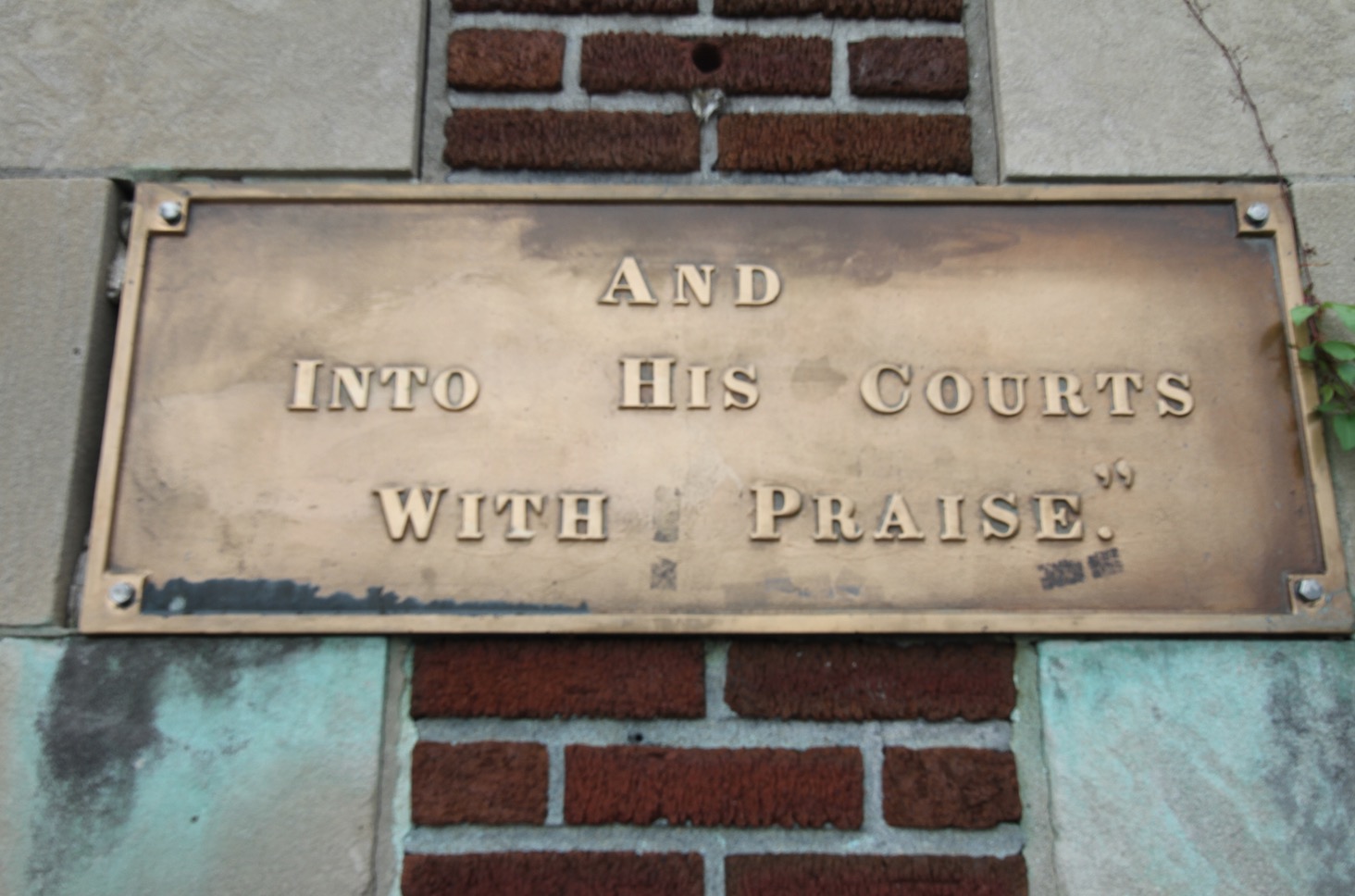

The first iteration of church building was the natural landscape itself along the beach. The current pavilion is inscribed with Psalm 24:1:

“The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it, the world, and all who live in it.”

It’s important to recognize that the most valuable real estate in Ocean Grove is not built upon or commercialized—unlike nearly every other inch of privatized beachfront property up and down the Jersey Shore. Here, nature was revered, celebrated, and preserved as part of God’s creation. The boardwalk is a gift to the public, maintained at some expense by the Methodist community, but you’ll find no amusement rides, cotton candy, tourist trinkets or pay-per-view beach passes. Only free musical events sponsored by the Methodist community are on offer. The lack of privatized commercial activity has a powerful effect on property values and desirability (as well as what might be called social equity or social justice) ten blocks away from the water. Since everyone in town has physical access to the waterfront, the value isn’t concentrated in a handful of expensive homes. That value is distributed throughout the entire community.

Open air pavilions were gradually supplemented by more substantial church buildings meant for seasonal use. In pre-air conditioning days the buildings were self ventilating with high ceilings, cupolas, and large doors and windows around the periphery, as seen here at Bishop Jane’s Tabernacle.

With 6,250 seats, the granddaddy Methodist church in Ocean Grove is the Great Auditorium built in 1894. It was the fourth iteration of the same basic building, as each successive version was larger and more substantial than its predecessor. Remember, this church began as a tent. Notice the high ceilings, upper windows and cupolas for natural passive ventilation like Bishop Jane’s Tabernacle. Also notice the huge barn style doors along the side walls that keep the church open to sea breezes during services, but secure the building when closed. The iron framework that made a building of this size practical and affordable – it was built in just 90 days – was a product of the same heavy industry that made a remote meeting camp site so desirable. That’s always the irony of new technology. It solves one set of problems while creating others.

Again, the generous use of public park space connects the Great Auditorium to the beach pavilion in a way that elevates the spirit, contributes to a better environment for everyone in town, and coincidentally makes properties more loved and valuable. As with many other places (Central Park in New York, for example) the most prestigious buildings are clustered along the public parks. That land could have been carved up into private back gardens, but the sense of community would have been compromised. This development style intentionally prioritizes shared interaction rather than insularity.

The quiet side streets of town are a study in incremental urbanism. These modest lots originally held tents. The tents were upgraded to cabins. The cabins were replaced by proper homes. The dirt roads, shared water wells, and outhouses were incrementally replaced by paved roads, sidewalks, and town services. First many small private investments were made, then collective funds were pooled to install more complex infrastructure with cash on hand. This is in contrast to current practice when all infrastructure is supplied up front and paid for with enormous amounts of debt.

This one group of homes speaks to the organic nature of growth in Ocean Grove. A tiny cottage remains next to an unassuming two story house on one side, with a significantly larger three story building on the other side. This is a snapshots of how the town evolved over decades. We don’t see this type of development anymore. Instead, entire subdivisions and master planned communities are built instantaneously and then prevented from changing in any way.

Ocean Grove has plenty of commercial activity along its main street (Main Avenue actually) and demonstrates that if the surrounding town is compact and walkable, the need for parking is greatly reduced. So is the need for super wide streets or special bicycle infrastructure. Most people can and do walk or bike to the hardware store, dentist, grocery store, ice cream parlor, restaurants, and post office. It’s not that people here don’t have cars or don’t buy things elsewhere. They simply have the choice of walking and participating in a more local economy. Notice how many buildings have a mix of commercial and residential uses. This flexibility allows the town to bend and adapt easily as the economy and culture shift over time. Yes, Ocean Grove has a tourist element, but it’s first and foremost a town for residents. It just happens to have a broad popular appeal, which coincidentally attracts outside visitors.

Like nearly all older towns in America, Ocean Grove endured a period of decline from the early 1960s to the 1990s. The Methodist community preserved the town through that dark time when most other places razed their historic buildings and urban fabric in a rush to install parking lots and Jiffy Lubes. In opposition to the overwhelming trends of the time, Ocean Grove made it illegal to drive or park within the town limits on Sundays, although that practice is no longer in effect. One of the reasons the town endured intact, and was able to be rediscovered and reinvested in by a new generation, was the presence of a religious community that had a higher calling and a longer event horizon than the dominant secular culture. There are lessons to be learned here even by people who may not identify with the church.

(All photos by Johnny Sanphillippo unless otherwise indicated.)

The Suburban Experiment killed the starter home. Here's how cities can bring it back to life.