We Need Growth. But Only If It Generates Real Wealth.

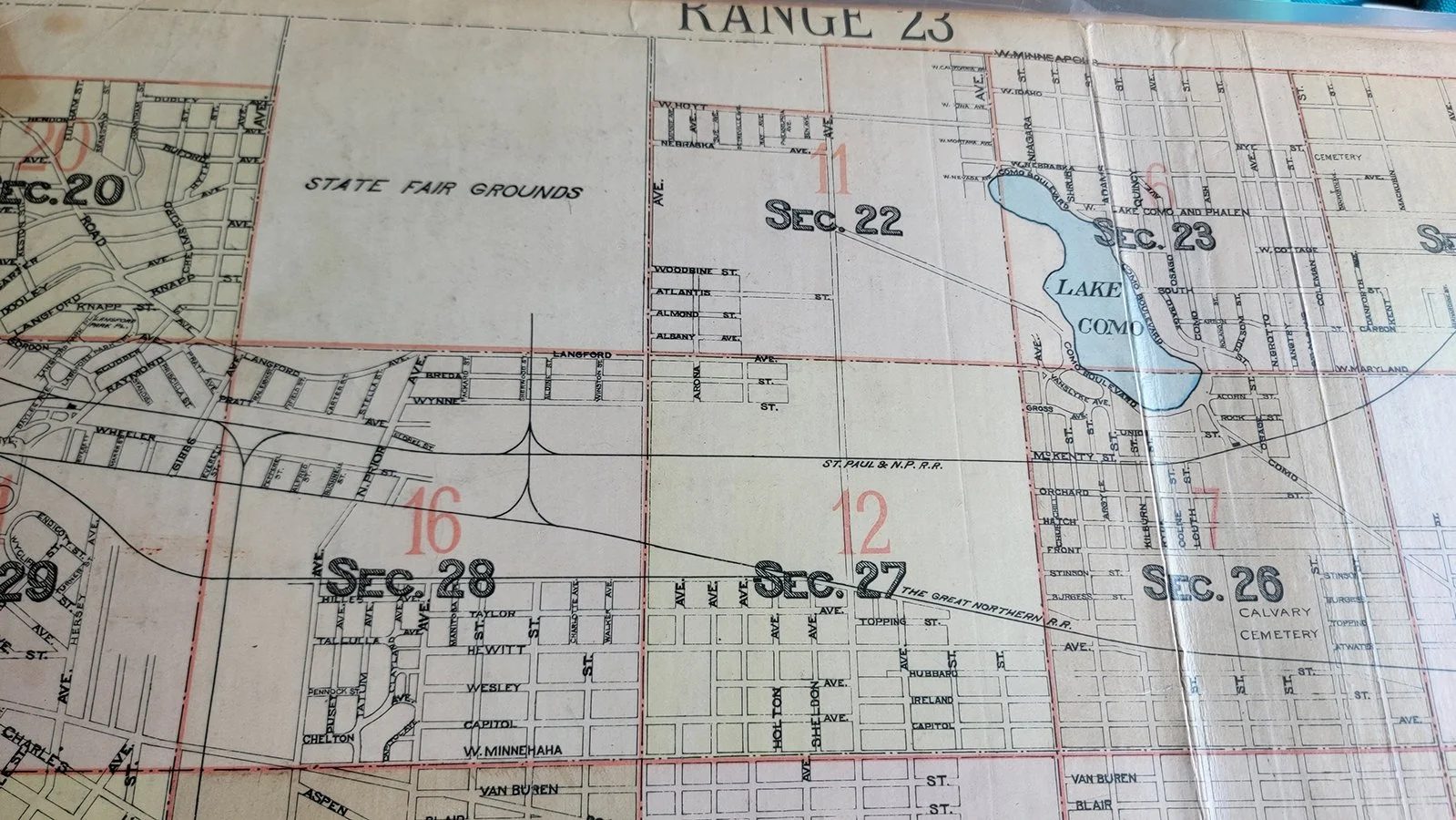

Image via Flickr

We are the inheritors of a profound cultural misunderstanding about growth.

Those born in much of the 20th century grew up immersed in the gospel of growth as an unqualified good—the simple result of the march of progress. The swelling suburbia of the postwar era was a self-evident good, mass car ownership a self-evident good, a rising stock market a self-evident good. We had more elbow room than our parents and their parents. We had ever-bigger houses, bigger yards, a higher material standard of living. And if we were uncomfortable with the way strip malls stomped across a once-pastoral landscape, we saw it as part and parcel of that same progress: This is the price of a society getting richer.

This post won't be devoted to refuting the gospel of growth-as-progress, because that would likely be preaching to the choir. It's not hard in 2019 to find people who have rejected the idea that a sane economic system can be premised on indefinite growth. The world millennials have grown up in is one in which economic recession, growing inequality, failing infrastructure and looming environmental catastrophe are the backdrop. And the hollowness of material affluence—its lack of connection to a meaningful, happy life, beyond a certain point of having enough to subsist comfortably—is, to many, more obvious truth than provocative heresy these days.

Rather, this post will be dedicated to what we need to prioritize, as a society, instead of growth-for-growth's-sake. What we need is productive growth that generates real, lasting wealth across generations.

Can’t Live With Growth. Can’t Live Without It.

Today, we cling to the ideology of growth not because we have any real expectation that it will make our lives richer, but because we can't imagine an alternative that isn't inhumane in its implications. We have to grow because the economy, and therefore people's well-being, depends on it.

The domain of Strong Towns is cities and the built environment, so let's talk about what it means to flat-out reject growth in the place you live. Local growth-control advocates seem too often to evoke a world in which the spoils of a bountiful way of life accrue only to those who got there in time to pull up the drawbridge behind them. "We're full; there's no room here to grow" is an easy thing to say for the owner of a home in San Francisco, in a state in which half of residents (and two-thirds of millennials) say they have considered leaving because of the high cost of living brought on by a shortage of homes.

Anti-growth sentiment for environmental reasons takes on an even more unseemly cast: when, for example, an anti-development activist suggests that restricting building in his city will reduce carbon emissions (a baffling claim which ignores that if people are deterred from moving to one particular city, they'll still live somewhere) the misanthropic implication not so far below the surface is that the maybe the actual people whose needs are met by growth are the problem, and shouldn't exist.

When growth stops, the pain isn't felt equally. If we were to utterly stop building new homes and businesses in retiree-haven Florida, whose economy is powered by real estate, the losers wouldn't be those retired doctors and lawyers in Michigan contemplating a move south. Those folks would still buy the beach homes they want. The losers would to a large extent be the working class already in Florida, priced out in the world's cruelest game of Musical Chairs.

And yet, it's abundantly clear that the legacy of growth even in (perhaps especially in) a place like booming Florida has been ruinous, and growth's ongoing trajectory promises to be more so. Tampa fights an epidemic of bursting pipes with an eightfold maintenance spending increase; and the fastest-growing city in the country, The Villages, hikes taxes 24% because growth is failing to pay its own way. We have overbuilt and under-invested and our world is literally falling apart on us.

To contemplate doubling down on suburban hyper-expansion is lunacy. To contemplate freezing our cities in time is equally unthinkable.

We absolutely need to better understand what growth is and when it serves us or doesn't. Simply railing against growth is as untenable as expecting growth to deliver us true prosperity. The observation that "If you're not growing, you're dying" is familiar as an obnoxious business cliché—but it is also a statement that is self-evidently true of, say, an ancient forest, and of many things we'd like to see not die for a very long time.

The question is what kind of growth we should cultivate and seek, that can serve as a process not of hypertrophy, of cancerous expansion, but of regeneration and renewal.

Or, in short, what does productive growth look like? Here are 3 rules:

Productive growth means filling in, fleshing out, and maturing.

Productive growth doesn't look like merely getting bigger—though a city building resilient wealth will almost certainly be getting bigger in its downtown core and other successful centers of activity, as modest buildings give way to more sizable ones while the value of that centrally-situated land rises.

Productive growth looks, very often, like squeezing more value out of what we've already built. In a podcast discussion with Strong Towns board chair Andrew Burleson, Chuck Marohn describes the myth of "built out." The modern era adopted the false notion that once a place has been built, it is finished and there is no more room for change.

The reality: walk just about any suburban American sidewalk. Look to your left. Look to your right. Go another 20 yards, and do the same thing. You'll notice there is an immense amount of land in which there is literally nothing there. If you make a place vs. non-place map of suburbia, the vast majority is non-place.

Productive growth looks like filling in those spaces over time with activity—an abandoned property becomes a new neighborhood business, a vacant lot becomes fertile ground for a community garden, a garage sprouts an ADU, an underused parking lot gives way to new apartments. It looks like replacing lower-value buildings with taller, grander, more permanent ones. It looks like sprucing up a facade, adding light posts and landscaping to a sidewalk, or watching street trees grow from diminutive shrubs to grand shade trees.

Productive growth looks like taking the places we already care for, and making sure they will continue to not only house the generations yet to come, but nurture those descendants’ full lives and bequeath lasting wealth to them.

There's a gorgeous oak tree in my yard that has got to be 60 feet tall and at least as many years old. It's extremely likely the person who planted it never got to see the glory of what it is today. Planting a tree is an act of faith, in a way. What if we treated our manmade environment with the same reverence we treat a tree that is likely to outlive us? What if we committed to seeding places that our great-grandchildren will adore and look upon in awe?

Image via Flickr.

Productive growth looks like ecological succession.

A mature forest is the result of a successional process. The first grasses and shrubs that colonize an area make way for small trees, then eventually a multi-layered canopy. The understory, too, adapts to the increased shade, as different ferns and mosses take root. New species carve out new niches—for example, the bark of an acacia tree becomes a fortress for ants, and vines thrive by wrapping around tree trunks.

Organically grown cities follow an analogous process. Chuck Marohn describes this process in Brainerd, Minnesota through historical photos: succession means that downtown in 1930 doesn't look like downtown in 1904, which doesn't look like downtown in 1870. The reisdents, as they could afford to, improved the buildings; they improved the infrastructure; things got not only taller, but grander and more permanent and higher quality.

Crucially, it means that those who liked downtown the way it was in 1904 didn't get to say, "Okay, we're done. We're establishing a strict height limit and historic preservation standards and none of these buildings will be allowed to be replaced or expanded upon."

Imagine if they'd done that in Times Square in 1943, and the 2016 scene below of one of the world’s most iconic public places had never come to pass:

Productive growth generates a real return on infrastructure investment.

If all you are concerned about is growing (a city, a region, GDP, a job base, a transportation system) within a particular, short-term time frame, for most places growth is not hard to achieve… as long as you're willing to take on debt. A city that borrows enough money can extend sewer, water, electricity and paved roads into undeveloped areas; if this isn't enough to entice developers, we can always throw some subsidy at them in the form of tax abatement or economic-development incentives, like you might fertilize and irrigate a farm field in an arid landscape to get it to perform. (Just mind that you don't ever stop fertilizing!)

Much of this spending does not produce wealth. This is particularly true of things that increase the amount of energy we expend, and space we take up, in going about our lives, without actually enriching those lives or fostering better connections between people.

Cities produce real wealth by letting people connect with each other, specialize and exchange goods and services, information and ideas. Many of our urban "investments," though, do nothing of the sort. Countless billions of dollars have been squandered on highway expansions that have merely allowed us to commute 30 miles at 60 miles per hour, instead of 10 miles at 20 miles per hour. The quality-of-life returns to this spreading out (or, perhaps more accurately, thinning out) of our cities are greatly diminishing. The long-term economic returns are far in the negative at this point.

“Planting a tree is an act of faith. What if we treated our manmade environment with the same reverence we treat a tree that is likely to outlive us? What if we committed to seeding places that our great-grandchildren will adore and look upon in awe?”

On a purely financial level, any entity that wants to survive must produce enough revenues to cover its expenses. We've spent beyond our means on public infrastructure, and taken up far more land than we can occupy productively. As a result, we’ve constructed a world in which most of our places don’t generate enough revenue to cover the maintenance of the infrastructure supporting them.

The right response to this failed model of growth, once we understand it, is not to eschew the promise of growth altogether, or to stop recognizing the need to continue to build places for ourselves and our descendants. Nor it is to double down on growth in the hope that we can build our way out of our predicament.

We’ve been living for decades on the urban economic equivalent of anabolic steroids. It’s time for some good old-fashioned diet and exercise. It doesn’t have to be true that the more we grow, the poorer we become. The key is to reorient the way we approach growth: instead of expanding our physical footprint and infrastructure liabilities, we need to wring real, lasting productivity out of the places we’ve already got.

In honor of the season, here’s a short adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” which illustrates the damage that zombie projects — large, ambitious projects that drag out for years or never get off the ground — can do to a place.