The Problem with Helicopter Urbanism

In his book The Art of Building Cities, Camillo Sitte explains that the best architects design the most impressive buildings and streetscapes from the angles where they first come into view to give a grand first impression. You design things from the perspective where you want the best experience.

This leads me to the antipattern of “helicopter urbanism”: designing cities from the top down (literally). The cities that are best experienced on foot look like a grey blob when viewed from above.

Beacon Hill in Boston. (Google Maps)

Zurich, Switzerland. (Google Maps)

You will struggle to design such a place from the top down. You cannot put someone in a helicopter and say, “Draw me a grey blob.” If we are drawing from the perspective of a helicopter, we are going to have helicopter-scale buildings and streets so that the city looks pretty from a helicopter. In reality, very few people experience a city from the air compared to the large number of people interacting with the city from the ground.

Consider Le Corbusier's neat, geometric “Radiant City.” All of the plans I found were either top-down or from a helicopter perspective.

The only people who could appreciate this view are those that get around via helicopter. (Source)

Jane Jacobs, in the middle of the 20th century, dissected how horrible these places turned out to be for those on foot.

I like to pick on Newport in Jersey City, NJ, because it is the opposite of what I consider good design. Block-sized skyscrapers divided by stroads. A ton of “green space” (although there are also a few real parks). Anytime a developer promotes a project in Newport, it is from a helicopter perspective.

Compare the helicopter renderings with the experience of Newport on foot.

A street leading into Newport. (Wiki Commons)

One of the nicer streets in Newport. (Google Maps)

The perspective from the air is not a very good judgement of how a place feels on the ground because the most important signals (how the buildings interact with and frame the street) are lost when viewed from afar. Good cities and buildings are designed from the perspective where they should be experienced.

This is one area where technology has the potential to help us. 3D computer aided design in theory allows architects and urban planners to visualize their work from any angle, and professionals do take advantage of these tools, but often it doesn’t translate to real attention paid to the view as experienced by a person on foot. I suspect if we saw how their projects really would look, they would have a harder time selling them to the community and investors.

The perspective from which we design a place is where we end up putting the most attention to detail and where that place is best experienced. If we design from a helicopter perspective, the place will be best experienced via helicopter (which very few people have the opportunity to do). If we design from street level, the place will be best experienced from the street. Here are those ‘gray blobs’ on foot:

Walking around Beacon Hill in Boston.

Walking around inside that gray blob we call Zurich.

There is a technique in virtual reality called foveated rendering whereby if you know where the user's eyes are looking, you can spend much effort making that area very detailed, and less effort elsewhere, and the technique is not perceivable.

Likewise with good architecture and urban design, we should spend the most effort putting intricate details where the eyes spend the most time and at the closest distance—i.e. the street level—and fewer or larger details where the eyes are very far away from or spend very little time looking, such as the upper floors and roof.

When a 10 story building sits next to a 50 story building, from afar they look very different. But when you're standing right in front of them, your eyes are likely to be focused on the street scene around you. Even if you look up, the height difference is not very noticeable. Most of our attention is going to be concentrated at what goes on at ground level as we walk past. Perspective matters.

This is what one of the tallest buildings in New York City looks like next to a humbler mid-rise building.

Even when you look up, the height differences don’t seem that crazy, and it’s hard to appreciate or even notice architectual details beyond a certain height.

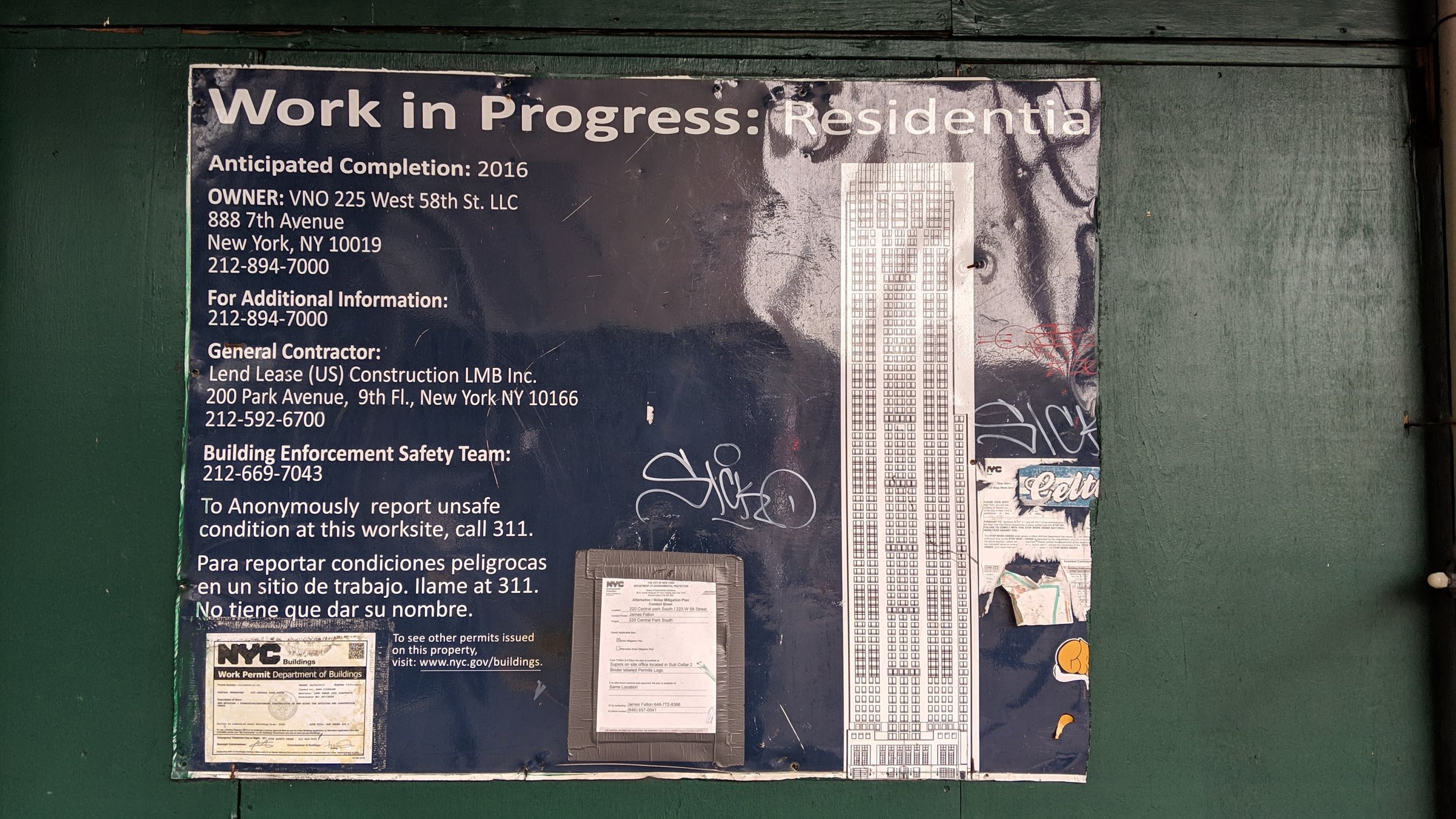

For example, at construction sites in NYC, a side profile of what the building will look like is often posted:

A Work in Progress sign posted on the outside of a construction site.

This works well for low and mid-rise buildings, but for tall buildings, there ends up being a disconnect because nobody will ever see the building from this perspective; it will always be obstructed (unless the building happens to occupy a corner lot that can be seen from afar, or faces a large open feature such as a park where you can stand back at a distance with an unobstructed view).

Instead, what people do notice, will remember, and influences the “neighborhood character” are the first few floors and how they interact with the street. Compare the photos below with streetscape of the Newport neighborhood above.

This staggared facade of a tall apartment building creates an interesting streetscape.

Faux-granularity by utilizing the ground floor of this tall building for small-scale retail is always a good idea.

It is important when we design a building or a neighborhood to look at how it feels and interacts with the street. Top-down plans and bird’s eye renderings do not convey enough information, and are an unrealistic representation of how people will actually experience a place.