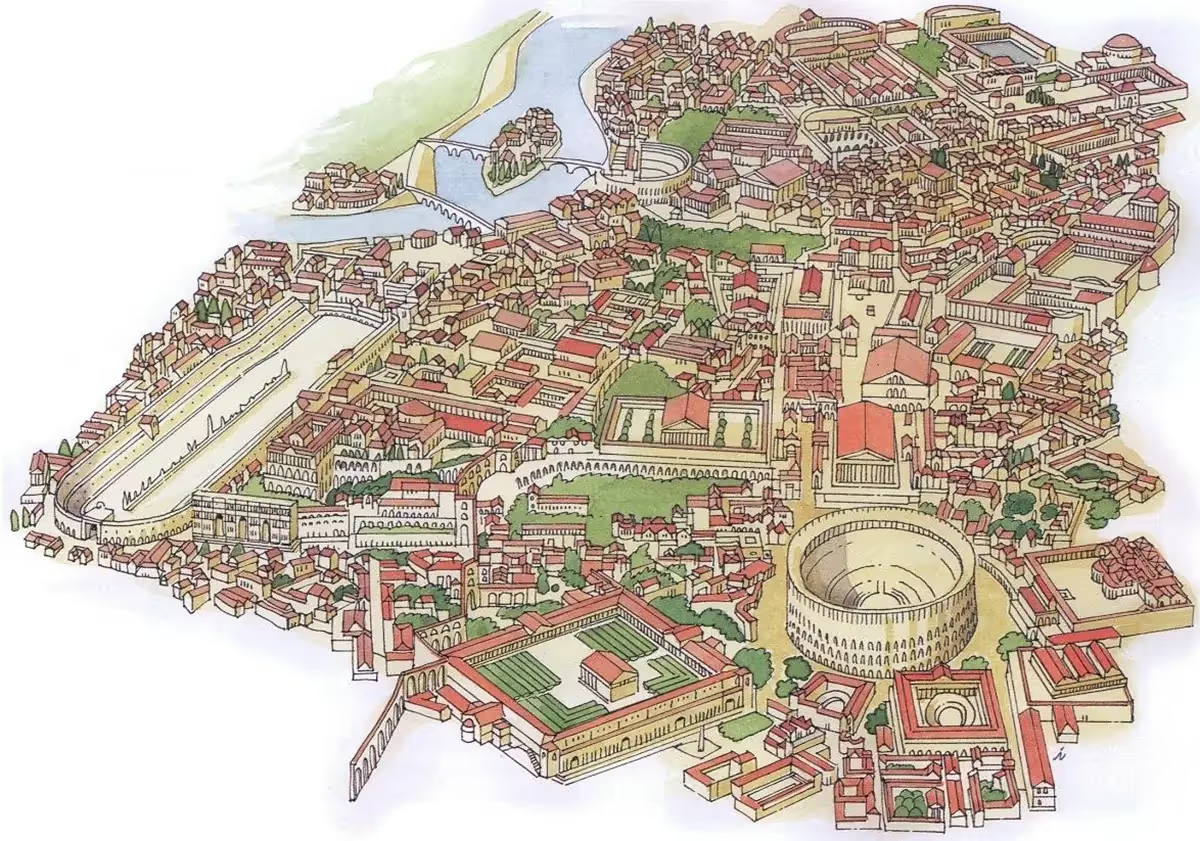

The traditional development pattern refers to the approach to growth and development that humans used for thousands of years across different cultures, continents and latitudes. Pre-automobile cities, big and small, in countless societies, share an eerie similarity of design. Public spaces are built to a human scale, where a person on foot can feel comfortable and safe. Most of a person's day-to-day needs are accessible by walking. Finally, traditionally-developed towns and cities are built incrementally over time, rather than all at once to a finished state.

When we look back at the way prior human civilizations built their places, when we study the way they assembled their streets, designed and placed their buildings and phased their infrastructure, we can start to appreciate the wisdom embedded in this approach, understanding that it was developed over thousands of years of trial and error experimentation. This is why Strong Towns refers frequently to the "traditional development pattern." We are describing not just a physical form but an approach to growth and development that history has revealed to be resilient and financially productive.

Four key features of the traditional development pattern are the following:

1. Traditional development is remarkably consistent in its design across societies and continents.

Visit cities around the world that existed before the advent of the automobile, and you'll find a clear commonality in these and other urban design features:

- Human-scaled design: Streets and public spaces provide a sense of enclosure, like an outdoor room, that makes people feel safe and comfortable. A space that is too expansive and imposing is uncomfortable to linger in.

- Walkable distances: The prevailing transportation technology for most of human history was two legs, and so traditionally-developed cities are compact enough that many daily needs can be met on foot.

- A fine-grained mix of uses: Homes and businesses are not strictly separated the way they are in many modern cities and suburbs. A common pattern found worldwide is a store on the first floor of a building, and an apartment upstairs in which the shopkeeper lives. This type of arrangement has persisted because it is cost-saving and flexible, and makes it easy to balance running a business with needs such as child care.

Notice how those three features appear over and over in the below slideshow of photos from around the world:

Traditional development is time-tested. These features of town design have survived disasters both natural and manmade—a natural selection process of sorts. We know they produce a functional, adaptable, and financially solvent city.

Further reading: Give it Another Century and We'll See How it Goes by Johnny Sanphillippo

2. Traditional development does not refer to a single architectural style or aesthetic.

The following photos are all of traditional development, even though the aesthetic influences vary by culture and geography, based in turn on pragmatic factors such as the available construction materials:

It's possible to miss what they have in common (notably the building and street proportions, layout, and mix of uses) by focusing on their differences.

Similarly, the traditional development pattern is not only a feature of bigger cities. It is prominent in small towns as well.

3. Traditional development occurs incrementally over time.

Today, we have access to heavy machinery, fossil fuels and other modern energy sources, and vast amounts of capital that make it possible to do huge leaps in development very quickly.

We can take on debt to pay for the up-front construction of streets, water and sewer systems, transit service, new public facilities like schools and parks, etc. When we do this, we are shifting the costs of acquiring them into the future, but enjoying the benefits of a finished building or neighborhood now. The question we must then ask ourselves is whether we will be able to sustain the maintenance of all we have built when the bill comes due.

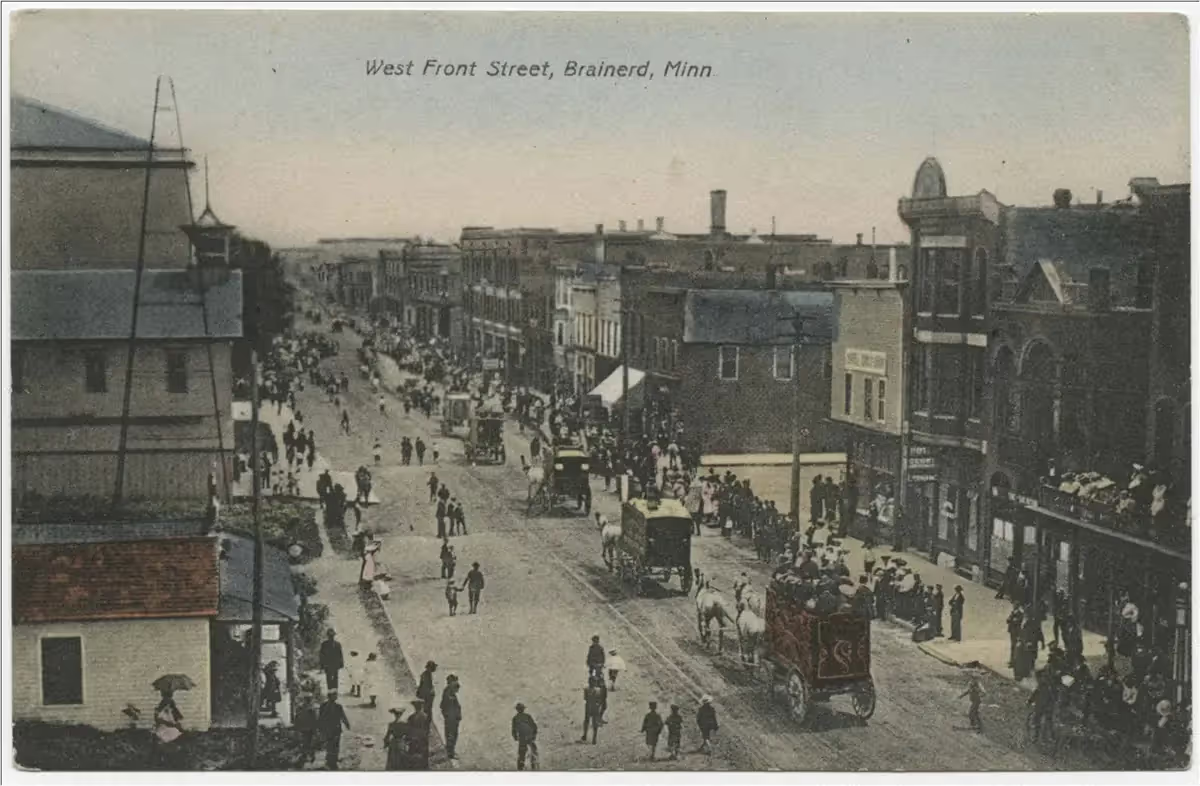

Our ancestors didn't have the same ability to build themselves into unsupportable debt. In "The Party Analogy," Chuck Marohn describes the incremental process of building out infrastructure in cities before a few generations ago, in the context of the historical development of Brainerd, Minnesota:

Consider the first iteration of the popup shack. Here we have a handful of people making small bets on the future of a place. There’s not much here beyond those little bets. No public sewer and water system. No paved streets. No public library. Not even a town sheriff. Maybe they could form a bucket brigade if something caught on fire, but that was the limit of what they collectively had to offer. This party was just getting started.

Of course, what the party needed was more people to show up and make additional little bets. As I demonstrated earlier, not only did more people improve the value of those prior little bets, they made the party better by adding to the capacity of the community. By the time we got to the early 1900’s, this city had a volunteer fire department. They had a law enforcement presence and the ability to deputize fellow citizens in an emergency. They had a rudimentary water system and a method of discharging their waste and garbage (largely into the Mississippi river). The more people who showed up, the better the city became.

In the last photo we can see how great this party has become. In the middle of the paved street is a stormwater drain. That stormwater system also would have served as a sanitary sewer system. A modern water distribution system was also in place. More people provided the wealth for a police department, fire department and public parks. While philanthropy built a public library, local wealth maintained it. This party was getting better and better and, most importantly, each improvement was legitimately achieved and financially sustainable.

Today, this incremental process is still apparent in many parts of the world. For example, on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, millions of people live in informal settlements called barriadas. Largely through the organizing efforts of residents, the city has gradually extended electricity, sewers, running water, and even mass transit to these places as the population has grown.

Expensive, ornate buildings can fit into a traditional development pattern. So can cheaply-constructed, utilitarian ones. These photos all exhibit the traditional development pattern in Mexico. The buildings and street in the Taxco photo (center) reflect a higher level of investment achieved over time, and those in Mexico City (right) reflect an even more mature stage of incremental development.

This does not mean that we are advocating that North Americans in the 21st century must go without electricity or running water. However, it is important to understand that the use of debt as a financing tool to construct whole, finished neighborhoods in one go is, in historical perspective, very new. And with it comes the temptation to expand our cities beyond our means, while failing to make ongoing, productive investments in neighborhoods that are already established, served by infrastructure we have already built.

Further reading:

- We're Not Dumber Than Our Ancestors, We Just Have Power Tools by Spencer Gardner

- Organically Grown Cities by Andrew Price

4. Traditionally-developed neighborhoods are never finished.

Under the traditional approach to development, all neighborhoods are on a continuum of improvement. The earlier series of photos showing the historical development of Brainerd illustrates this evolution.

A traditionally developed neighborhood can play host to a remarkable array of different land uses and inhabitants over time. Its buildings can be repurposed, reoccupied, and adapted to different uses.

In the post-World War II suburban era, we have largely abandoned this practice of building infinitely adaptable places. We now build places all at once, to a finished state, and with the expectation (often enshrined in zoning codes, HOA rules, or the like) that they will not evolve at all once inhabited. Places built according to this suburban model almost inevitably decline and lose value over time, rather than being adapted and renewed continuously as economic and demographic conditions change.

Further reading: The End of Incrementalism by Charles Marohn

For perhaps the most dramatic example possible of the power of incremental development to grow the wealth of a place, here are three photos of New York City’s Times Square from three very different eras:

The traditional development pattern is the only way of designing and building human habitat that has been tested and refined by thousands of years of experience.

The modern contrast to the traditional development pattern is what Strong Towns calls North America’s Suburban Experiment. Since the mid-20th century, more often than not, we have begun to build neighborhoods at a huge scale, all at once, and to a finished state. This debt-fueled approach has produced remarkably rapid growth and some very pleasant, even luxurious environments. However, it is also increasingly clear that it has saddled us with unmanageable amounts of debt and liability, and resulted in places that are very fragile to economic disruption.

It’s time to re-learn the lessons of the traditional development pattern. This is the key to building Strong Towns.

.webp)

.webp)