What If You Built Hundreds of Miles of Roads and Nobody Came?

Many American cities have a pavement problem: specifically, there’s too much of it. But without digging into some numbers and putting them in context, it’s hard to understand what “too much” really means, or looks like.

In Palm Bay, Florida, we have a great example of what this looks like. The most populous city in Brevard County is in major financial trouble despite a history of consistent population growth for decades. Palm Bay city officials asked geoaccounting firm Urban3 to perform an in-depth analysis of the mismatch between the city’s tax revenue and liabilities, and how their city might be able to recover from the ramifications of an extreme embrace of auto-oriented development.

Roads…and roads…and roads.

Figure 1. Click to view larger image. (Source: Urban3)

Perhaps the most glaring issue in Palm Bay is surplus roads. There are 958 miles of roads in the City of Palm Bay—enough to reach Baltimore if you stretched them out end-to-end. This amounts to 46 feet of road per person in Palm Bay.

Without context, this figure may not stand out as startling, so let’s compare that to other Florida cities:

Gainesville: 22 feet of road per person

Miami: 10 feet per person

Naples: 3 feet per person

That’s not a typo. Palm Bay has more than fifteen times the pavement to maintain per resident that Naples does. Sure, Naples is much smaller geographically, but it still has a similar population density to Palm Bay. It has 1,772 people per square mile while Palm Bay has 1,675 people per square mile.

Here are Google Street View photos of major, centrally located intersections in each city:

How is this possible? How can the amount of road mileage in two seemingly comparable cities vary by such an outrageous amount? The explanation has to do with Palm Bay’s development pattern, and its wholehearted embrace of the Growth Ponzi Scheme. Let’s unpack its history to see what created Palm Bay’s road epidemic.

Figure 2. Click to view larger image. (Source: Urban3)

Vacant Property

Palm Bay has a huge number of vacant lots distributed throughout the city’s neighborhoods. This image, taken in the middle of Palm Bay, outlines all vacant properties in red. 16 percent of the city’s land, or 13.4 square miles, is vacant. But it gets worse: only slightly more—21 percent—is residential and actually has a home built on it.

With homes spread so thinly, the amount—and cost—of roads, pipes and other infrastructure soars above what is necessary.

Why is there so much vacancy in Palm Bay? This does not occur in a typical suburban neighborhood. To answer this, we need a brief history lesson.

General Development Corporation

In the 50’s and 60’s, a development company named General Development Corporation (GDC) established communities across Florida. Their strategy was to buy and subdivide huge tracts of land, pave a grid of streets, then sell cheap lots to people up North, promising they would gain value. GDC’s real-estate strategy was successful, oftentimes selling lots to customers who never even saw the property. Some built a house on their purchased land, but many did not.

GDC used this approach in Malabar Point, a subdivision of Palm Bay. They purchased and platted what would become the new community in 1959, just before the City of Palm Bay incorporated in January of 1960. GDC was behind the development of Palm Bay from then forward, and the city was built as a gigantic expanse of residential subdivisions, with no downtown and no mixture of commercial land uses within its neighborhoods that might have reduced residents’ need to drive. Because of the way the lots were divided and sold, homes were built seemingly at random, instead of being clustered around a downtown core.

GDC sold its customers promises of vibrant new cities with modern amenities that, in many cases, never emerged. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that GDC leadership was accused of fraudulent home sales. In 1991, GDC filed for bankruptcy but, unfortunately, the damage was already done in Palm Bay.

Figure 3. Click to view larger image. (Source: Urban3)

The Compound

The worst of the GDC aftermath is an area of Palm Bay known as “The Compound”: 2.8 square miles of completely undeveloped land with 65 miles of paved roads, according to Urban3’s analysis. Sixty-five miles of roads would cost Palm Bay over $2.5 million each year to maintain.

The Compound’s streets are not being maintained; however, while money is not being wasted on road repair, The Compound is still costing the city in other ways. According to Will Creasy of Urban3, the city police and fire departments are often called for accidents caused by both reckless driving and recreational activity, all of which poses a major safety concern on top of the financial liability.

Fire in the Compound, Palm Bay. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Palm Bay and the Growth Ponzi Scheme

Annexation

In an attempt to turn things around, Palm Bay has grown by taking on debt and acquiring even more land. Most recently, the City annexed more than 28 square miles, increasing the size of Palm Bay by 33.7 percent. Strong Towns readers will quickly recognize this as an example of what we call the the Growth Ponzi Scheme, in which new development is counted on to provide a short-term burst of revenue to pay for the infrastructure liabilities of older neighborhoods. We’ve written about the pitfalls of annexation before. Palm Bay’s root problem is already an unproductive, spread-out development pattern—growing even larger in land area is unlikely to help.

Additional Debt

Additionally, the City proposed a General Obligation (GO) Bond series of up to $150 million for road repair at the end of last year. It passed at 66% and the first series of bonds should roll out this summer according to the City website. This is yet another form of taking on debt, digging a deeper hole. Despite a change in city management, road repair remains a top priority. This does not mean that roads in need of repair should simply be left alone, but this tactic treats the symptoms as opposed to the cause.

So What’s the Solution?

Palm Bay has an extraordinary amount of infrastructure: achieving balance won’t be easy, but it has to mean adding population without adding new roads. Urban3 has demonstrated in city after city that walkable, mixed-use downtown areas are the cash cow subsidizing unproductive development. Palm Bay lacks a historic downtown core—but it could seek to create one.

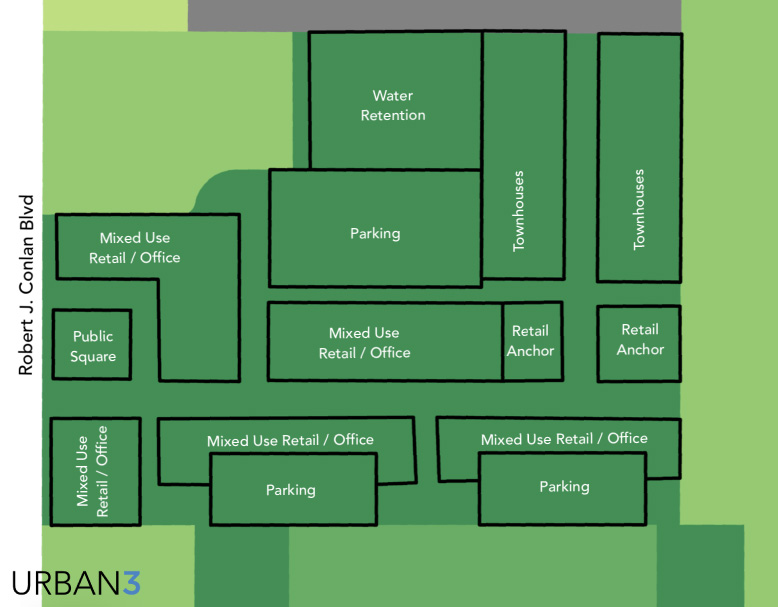

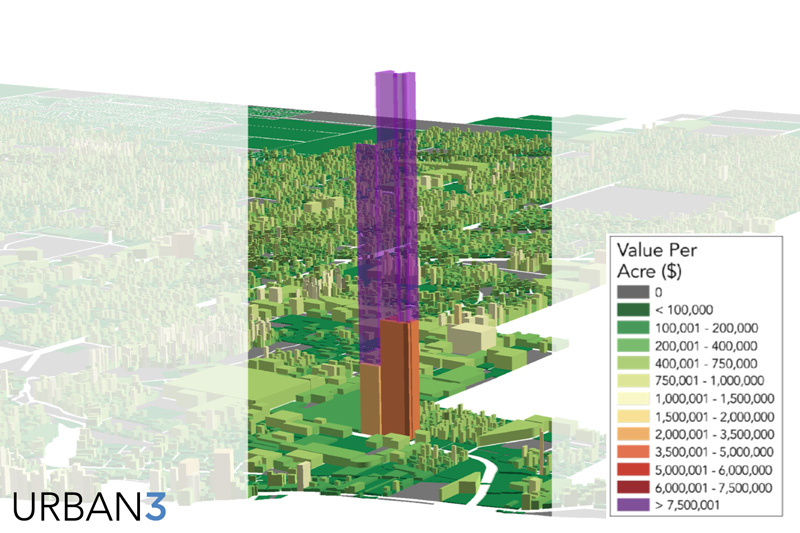

Urban3 presented an urban design using mixed-use development in a potential site near the middle of Palm Bay (Figure 4). Based on similar construction in the area, Urban3 projected the land value of their hypothetical design using a 3D model. In Figure 5, the opaque orange spike represents the lowest possible value while the transparent purple spike above it represents the highest possible value of Urban3’s mixed-use design. If constructed, the actual value of this project would lay somewhere between the two spikes. As you can see, even a worst-case-scenario yields some of the most valuable property in Palm Bay.

This project would take a major step in permanently solving Palm Bay’s problem. How? Multiple stories literally stack value on top of value. Using existing infrastructure avoids additional liabilities that are involved in building a new community or big-box store. Mixed-use development means the space is used more hours during the day and is hence more productive. It is a flexible design—spaces can be put to different uses as needed—which enhances the site’s long-term resilience. The list goes on.

Palm Bay needs to get back to the basics of the Strong Towns approach: use its existing infrastructure as a platform to build real wealth, instead of gambling on more growth at the edge of town. Even places that do not face the extreme circumstances seen in Palm Bay—a street network that would stretch from Florida to Maryland and huge swaths of vacant land—can benefit from this tried and true approach.

Cover photo via Flickr.

Robert Sulaski is an intern with Strong Towns and the geoanalytics firm, Urban3, for the summer of 2019. Rob is pursuing an undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) in Media and Journalism, concentrating in Interactive Multimedia, with a minor in City Planning and Urban Studies. Growing up in the Asheville area has given him a love for the outdoors, southern hospitality and good beer.

Rob is a storyteller at heart with a passion for exciting, walkable communities. With previous digital communications experience, he is excited to use these skills in the context of planning. Prior to joining Strong Towns and Urban3, he studied in Pamplona, Spain where he found an even deeper appreciation for urbanism and also produced a study abroad/travel podcast, sharpening his storytelling skills. He will be writing about Urban3’s work throughout summer 2019 before returning to UNC for his senior year.