Can This Texas Suburb Create a Downtown of Its Own?

A project involving master planned development, tax increment financing (TIF), and the questionable allocation of transportation resources does not sound like the Strong Towns cup of tea. In fact, Strong Towns has been consistently critical of manufactured downtowns for many reasons, primarily the fact that such projects are often costly gambles. When a whole neighborhood is built according to the large-scale vision of a single developer, it doesn’t benefit from the feedback that allows for a great place to incrementally evolve over time in response to the needs of its users.

Is there ever an appropriate time and place to think big and plan a whole neighborhood out of nothing? Sometimes, under less-than-ideal circumstances, it might still be the best option. Specifically, when you have a large piece of land that existing infrastructure has made far too valuable to waste on a business-as-usual suburban development approach. This is the story in Leander, Texas. Through flexible development plans, low-risk financing and a new transit station, Leander is working to make the best out of the hand they have been dealt.

Leander, Texas

Leander, Texas is a northern Austin suburb about 23 miles from the state capitol. What began as a small, rural community built around an old railroad has been leapfrogged by Austin’s suburban expansion. Although Leander is part of one of the top 10 fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the nation, most of this growth has occurred in the nearby cities of Round Rock and Georgetown. Today, the population of Leander is roughly 50 thousand and there is not much commercial activity; it’s mainly a bedroom community.

Figure 1. Click to view large image. (Source: Urban3)

In cities all over North America, the geoanalytics experts at Urban3 have found that walkable, traditional downtown districts are the economic engines of their cities, visible on a map as “spikes” of economic productivity. Leander’s problem: it has no such downtown. Figure 1 maps out the value per acre (VPA) in Williamson County. Round Rock and Georgetown both show spikes of economic activity where a downtown and central commercial district lay, but Leander’s is nonexistent. The city consists of low-value auto-oriented development, a money-losing pattern. However, Leander now has a chance to save itself from financial danger.

A place once brought to life by rail is now along another life-giving rail. The Capital Metro Red Line runs from Leander Station, which opened in 2010, into Austin. While some may question why an expensive commuter rail station was built more than 50 minutes from Austin in an area with a completely auto-oriented development pattern, there is no doubt that it is a huge asset for Leander. A hospital and community college have recently been built and will continue to expand in order to accommodate and encourage growth.

With the metro station, new hospital and new community college, one thing is for certain: Leander will undergo a great deal of change in the coming years. The city must take control to dictate what that change looks like. Its decision is not simply a matter of aesthetic preferences. Rather, the city’s decision on how its future will look might easily be a matter of financial life and death.

One of the most critical areas for the future of Leander is a 115 acre property south of the St. David’s Emergency Center and north of Austin Community College near the metro station. Will Creasy, Urban3 analyst, explains the importance of the location:

“Thanks to the transit stop, this land is too valuable to be ignored. Something will be built there either way. We can either choose to build a mixed-use neighborhood that can sustain itself in the long term or we can choose to fill it with big box stores that return a quick income but all too soon become empty, ignored shopping centers.”

As Figure 1 makes clear, there is very little economic activity currently. This property is more than an opportunity. Leander simply cannot afford to see this 115 acres fill up in the same pattern as the rest of the city—spread-out subdivisions or big-box retail. It needs something radically different, in a place where developers aren’t used to doing different.

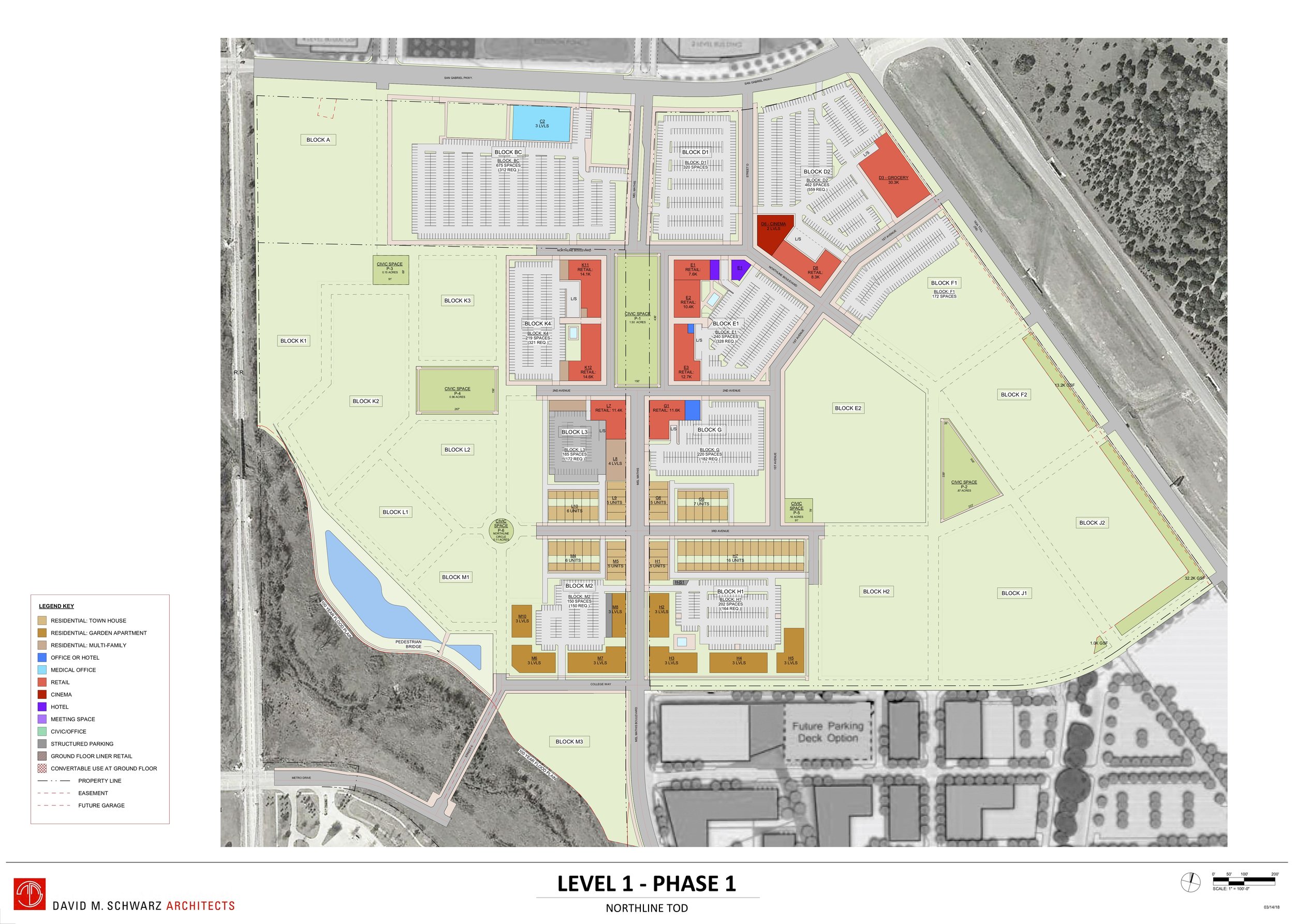

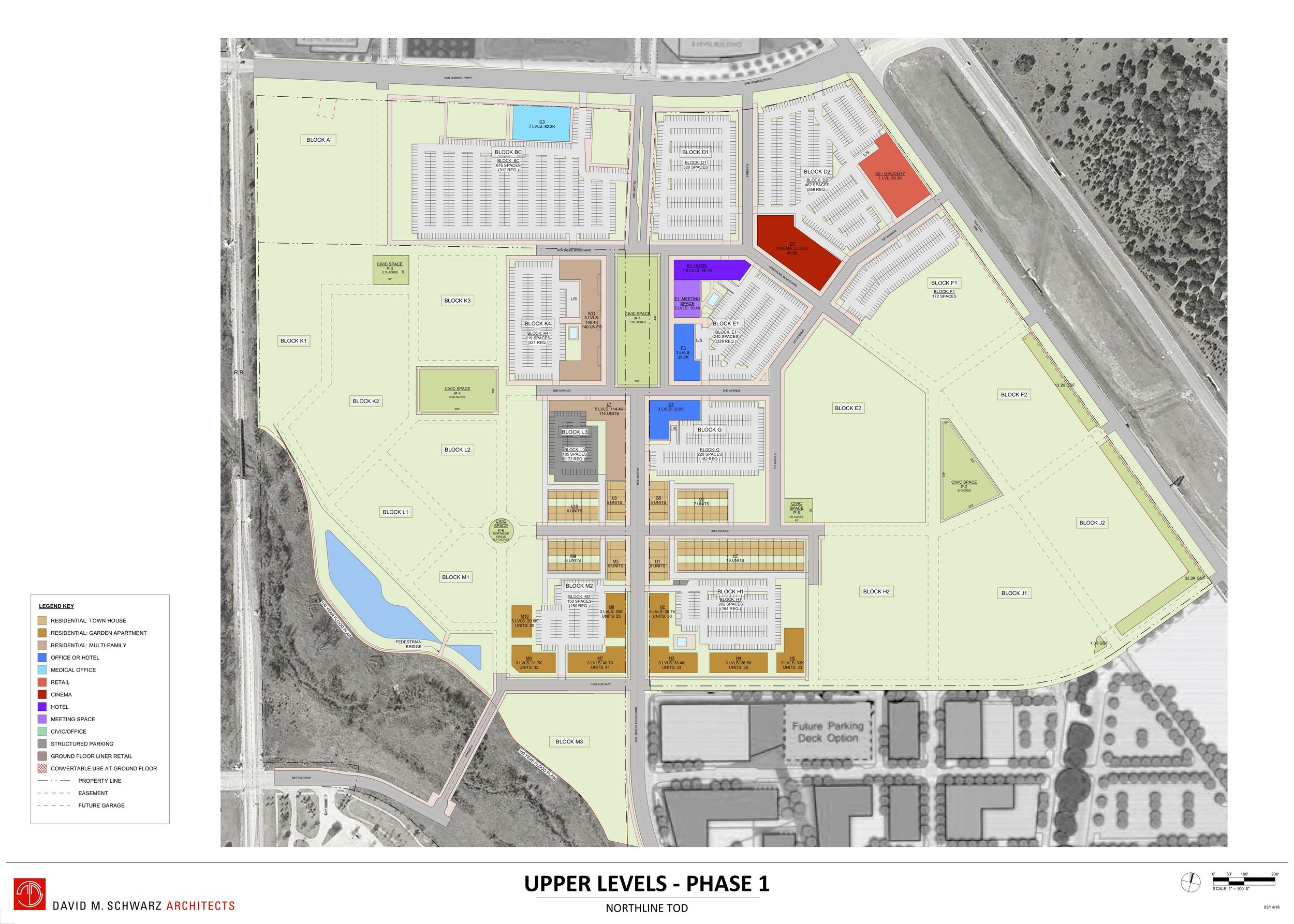

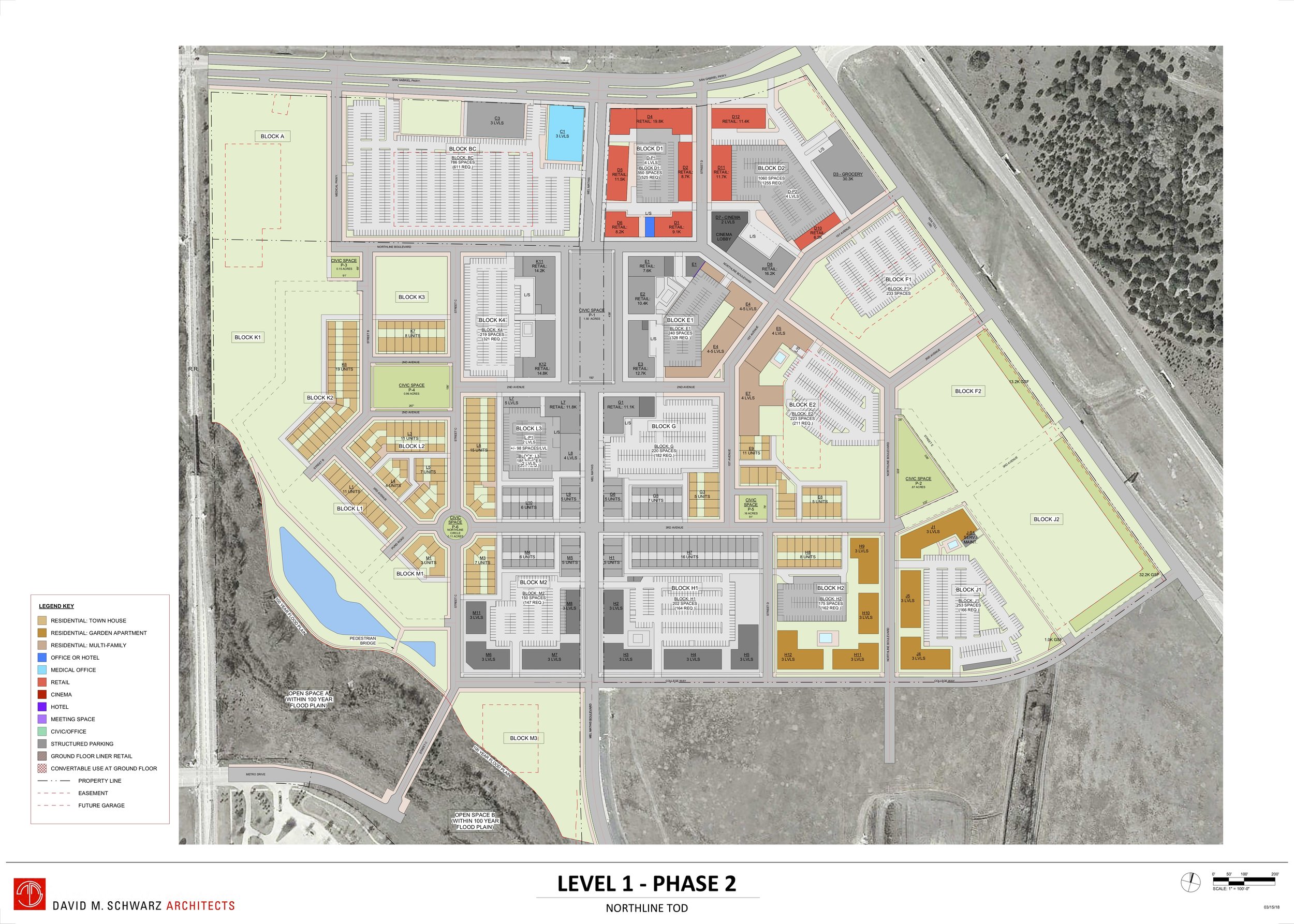

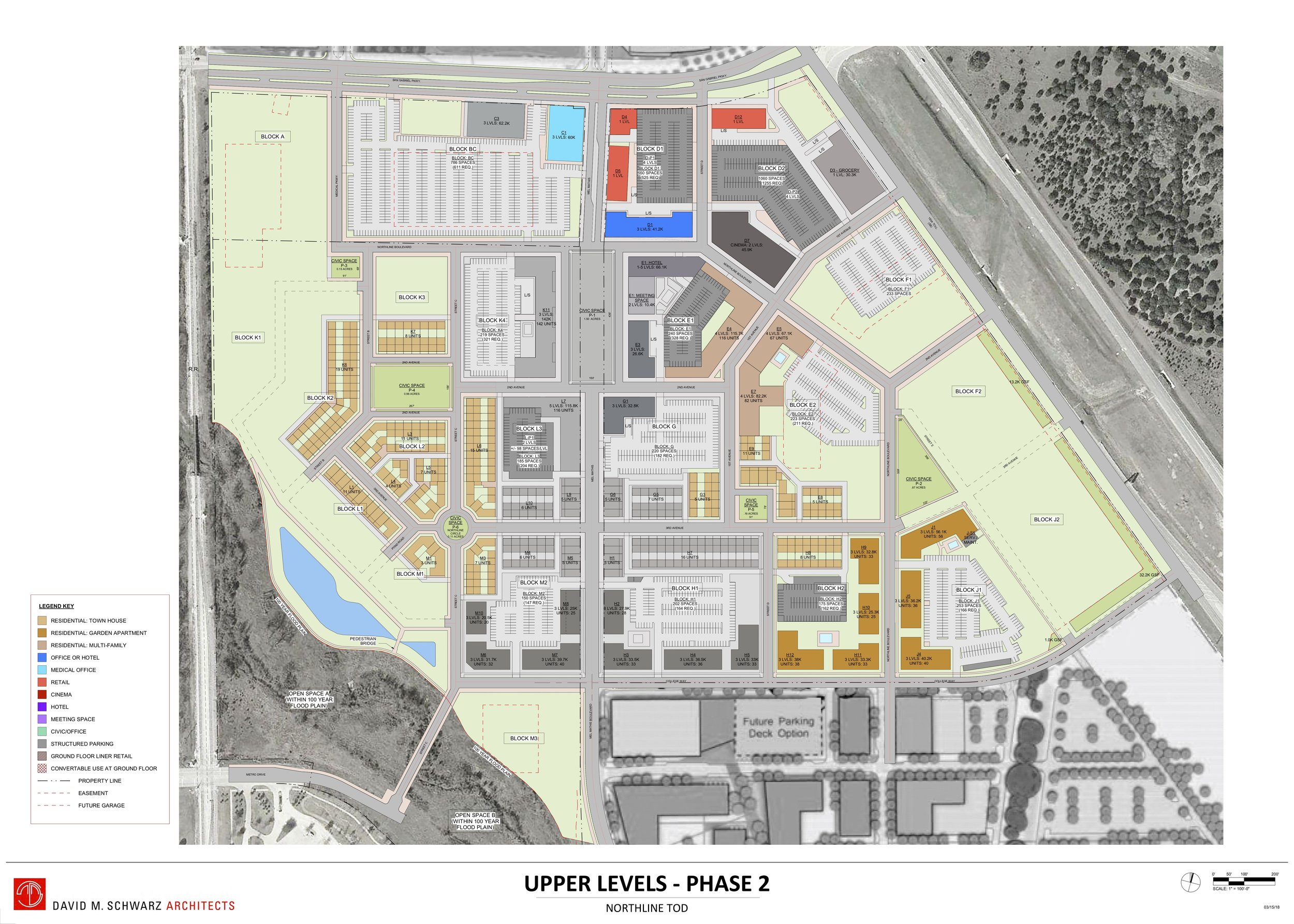

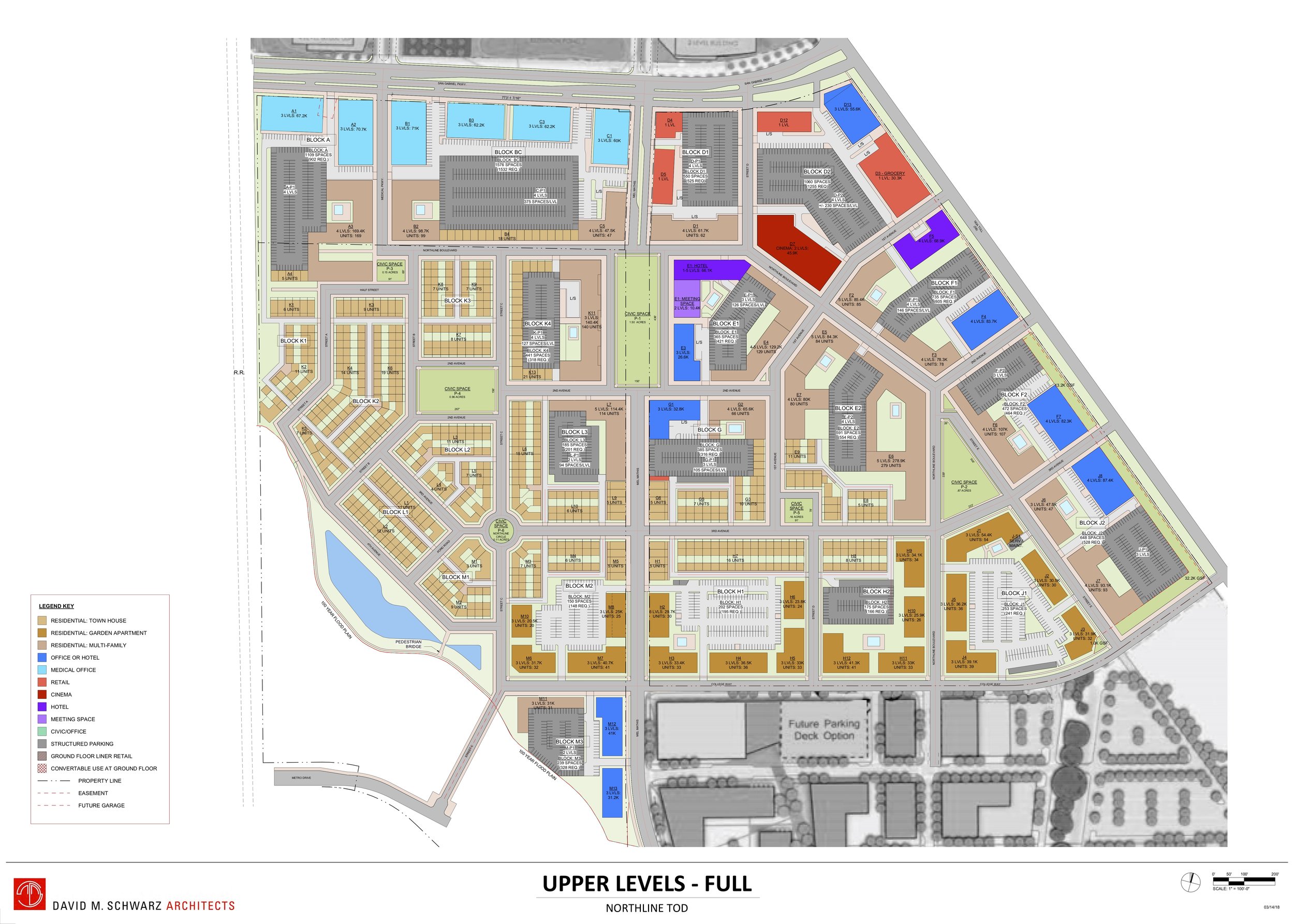

Figure 2. Click to view large image. (Source: David M. Schwarz Architects)

The Northline Project

Bearing this is mind, the City of Leander hired geoaccounting firm Urban3 to help inform the best financial decision for the property by projecting future revenue under different scenarios for what kind of development would be allowed and built on the 115 acres near the train station.

Meanwhile, Northline Leander Development Company, LLC had proposed a project, Northline, to be constructed on the site. Urban3 found that this mixed-use transit-oriented development (TOD) is Leander’s best shot at creating a downtown and a future for the city along with it.

Figure 2 shows an outline of the proposed project between the new hospital, community college and transit stop. The full plans feature more than 2,500 residential units and over 120 thousand square feet of retail space. The plans also include 360 thousand square feet of office space, a cinema and hotel.

The project has been broken down into three phases which build out from the center. In an interview last week, Alex Tynberg, president of Northline Leander Company, said, “Phase 1 horizontal infrastructure plans are going to be submitted to the City of Leander next month.” Tynberg anticipates breaking ground by the end of 2019.

Current Plans By Phase

Urban3 believes Northline will create a critical source of wealth for the City of Leander if fully built out. Figure 3 shows the estimated land value per acre (VPA) in Leander during and after Northline construction. The opaque purple spikes represent the project land VPA in 2025 after Phase 1 and 2 have been completed. Going above these values in transparent purple is the projected land VPA for 2038 after the completion of all three phases.

Figure 3. Click to view large image. (Source: Urban3)

Compare that purple spike to the entire rest of the city: clearly, Northline has the potential to become the most valuable land in Leander. Urban3 analysts say that while the projected values dwarf what currently exists in the surrounding property, building higher-density residential would increase the land VPA of a much larger area around Northline.

Red Flags

So what’s the catch? Well, there are a few red flags about this project that may have you skeptical of the Northline project; after all, being critical and asking questions is crucial to good planning.

First, this is a master planned community (MPC). While MPCs can result in success, they have a bad rap. There are many examples of them not evolving to meet community and market needs in the long run because they are not typically designed to change. (Here’s an all-too-typical example of the kinds of struggles that are common.) Northline, however, will seek to avoid this using phased development and, importantly, flexible spaces.

Tynberg said each phase is “fluid,” and that after phase 1 is constructed, “the buildout will be market driven.” In addition to flexibility in each phase, the spaces themselves will be built to be adaptable. Rather than big-box retail, a mix of small spaces for retail, office and residential will allow Northline to serve many purposes and hold value in the long run.

There are examples of master-planned communities done well in similar situations. Baldwin Park in Orlando, Florida, began as a Navy training center just outside of downtown. Once the training center shut down in 1998, it left a 1,100 acre vacancy within city limits. Recognizing that sticking to the status quo would result in developers filling the area with standard suburban development, Orlando planners chose a master-planned, New Urbanist design. Strong Towns’s Daniel Herriges visited the community and argues that it works well for several reasons. These include its connection to the surrounding areas, decreased car dependency, and flexible work-live spaces. Northline can also hopefully check these boxes and be a successful MPC.

Perhaps the most concerning aspect is the use of a tax increment reinvestment zone (TIRZ). This is Texas’s name for what other states usually call tax increment financing (TIF). TIRZ/TIFs have a bad reputation for causing more harm than good because they pull property tax revenue out of a city’s general fund in order to pay off loans used to jump-start development. This can take money away from school districts and other general public needs.

Figure 4. Click to view large image. (Source: Urban3)

Big-box retail buildings have an average lifespan of 15 years yet a TIF normally lasts 23 years. A suburban big-box development receiving TIF could actually take property tax revenue from the city for longer than they are operating. It’s essential, if you’re going to use this financing tool, that you avoid this pitfall. The Northline TIRZ is a short-term financing plan which only runs for a total of 13 years. This amount of time pales in comparison to the lifetime of the completed project.

This TIRZ will not deprive schools and other public amenities of funds, either. Only 50% of property taxes from Northline will go towards funding project infrastructure while the other half will be put into the general fund as seen in figure 4. That is compared to a traditional TIF which only returns a small, constant base of revenue to the general fund, despite the increase in property taxes. This low-risk financing option provides just enough spark to get the initial project started and will result in long-term gains for Leander.

Leander’s unusual situation comes down to its metro station. The existence of commuter rail Leander may cause some to wonder, “Why did the line not run through Georgetown and Round Rock? How come Leander?” For our purposes, though, it doesn’t matter why or how the station ended up in Leander; that is an entirely different story to write. The metro is there and it is running. The question we should be asking ourselves is, “How can the city best capture real value out of Leander Station?” The answer is smart development which takes advantage of the station and creates sustainable wealth for the city.

As planners, developers and community members, we need to work with the hand we are dealt. In Leander’s case, they have a bad hand with one wild card. Leander cannot afford to use their wild card for something ordinary; the Northline land is its chance to do something bold yet smart, do the math and think about the long-term future. In doing so, Leander can become a stronger city.

Our most famous case study revealed the high cost of auto-oriented development. But what if a little creative rearrangement could make things a whole lot better?