The Problem with Drive-By Urbanism

How do you solve a problem like a sidewalk?

Back in July, The City of Austin released a timeline outlining the creation and potential passage of a new land development code. This came after the previous multi-year initiative, CodeNEXT, was canceled in 2018 after concluding the process had gone awry.

The new timeline, via City of Austin.

The reasons behind restarting the process make sense: Austin is seeing some of the largest growth of any city in the United States. The population of Austin has changed significantly over the past 20 years. 656,562 people lived in the city in the year 2000. That number is expected to cross the 1 million mark in 2020.

In order to accommodate for this growth, the city has zoned for multifamily to be developed in specific parts of the city, mostly along transit corridors. In theory, this is effective because this means that individuals have near-direct access to buses and can rely less on cars to carry out their day: go to work, shop for groceries, attend events and go out in the evenings, etc.

In practice, it does not work that way.

The problem with this form of urbanism is this:

Simply allowing for more development to happen along one street does not create an urban neighborhood with more than just housing units and a few small businesses.

Focusing all development along these corridors does not provide enough units to meet the city’s Strategic Housing goals (it is currently 6,000 units behind its pace for 135,000 in ten years)

Placing more individuals along major roads designed to get cars as quickly out of town (South Congress, South Lamar, North Lamar, Burnet Road, etc.) creates a conflict of perceived safety and does not solve the problem of walkability.

Living near a busy road increases your exposure to pollution and can cause a host of issues including asthma, dementia and premature death.

Drive-By Urbanism on 7th Street in East Austin, image via Austin Business Journal.

With the new development code, there is a strong belief that the issue of housing development will be addressed in a way that will allow for the city to meet its goal of a compact and connected Austin, per the Imagine Austin plan. However, if the plan is even a close continuation of what occurred during the CodeNEXT process, what we will see is more of the same: drive-by urbanism and a code that doesn’t address a need for more housing, let alone quality urban neighborhoods.

Using the tenants of compact and connected from the Imagine Austin plan, here is my vision for better Austin urbanism through land reform.

A Compact Code That is Clear and Concise

Compact means two things: compact in the length of the written rules and compact in the type of development created.

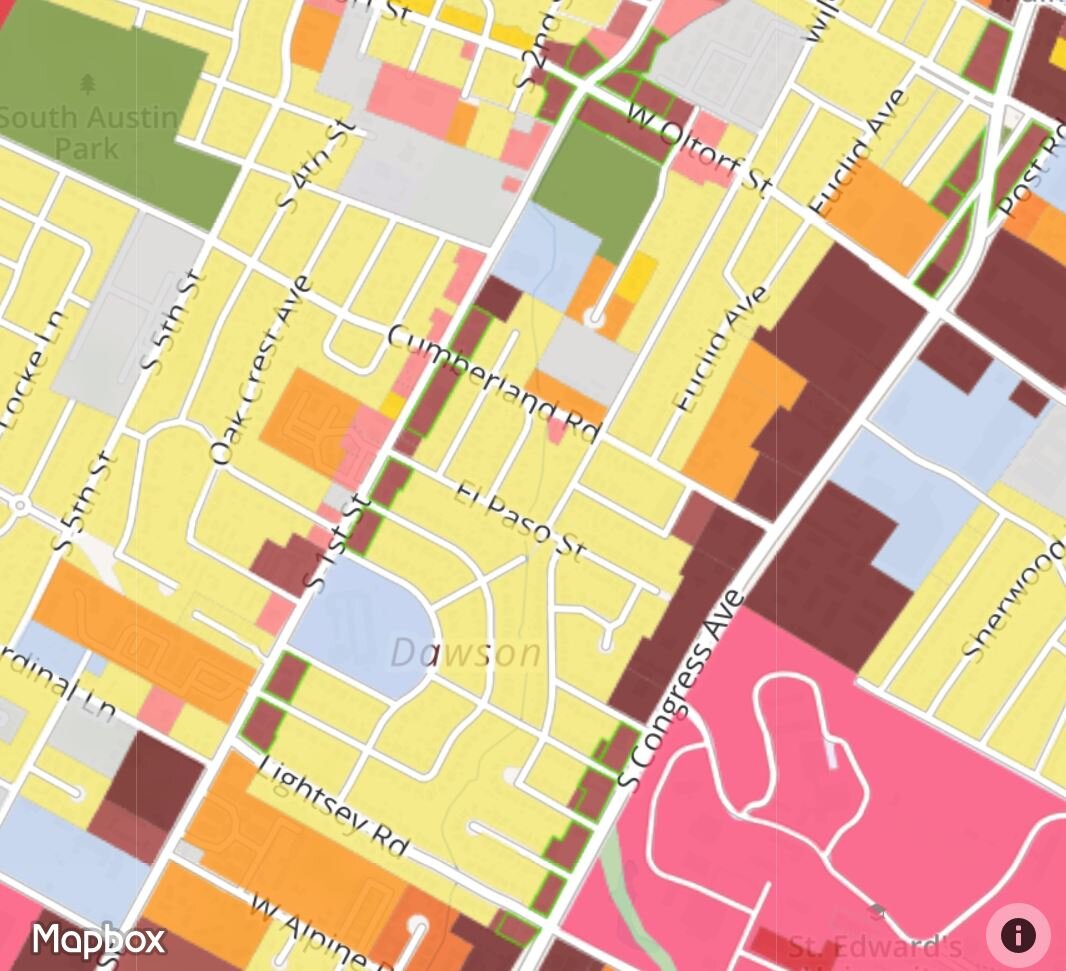

An example of single-family zone (in yellow) existing in close proximity to two streets with transit and more dense development, via City of Austin

A compact zoning code means that it is easy to use and easy to implement, ideally saving time, stress and energy for all parties involved and reducing the costs of development in the city. The new zoning code should have less uses/zones than the current code and be straightforward enough that a non-design professional can easily understand what they can build on their property. A simple system that just has maximum heights, lot setbacks and impervious cover limits would allow for more time for design and/or shorter project timelines. This could also allow for creativity in regards to the number of units provided on smaller lots, allowing for smaller scale missing middle housing to be a viable option for many. Any complexity in treating zones differently should be solely related to preservation of existing parkland and environmentally critical areas.

The importance of not developing in those environmentally critical areas is also why the code should focus toward compact development within existing neighborhoods. Per the images shown, even in the last version of CodeNEXT there were many locations where spot zoning and neighborhoods within walking distance of transit were kept as single family. Zoning should be implemented in such a way that true urban neighborhoods can flourish and not simply be relegated to single streets. This also means removing single-family zoning from the city center, particularly in neighborhoods that are not at risk of gentrification.

An example area of where single-family zoning should be removed, which represents areas within 3 miles of downtown and fairly direct access to streets or transit. (made in GoogleMaps)

A Connected City with Great Streets for All Austinites

As a rule, sidewalks in Austin are bad. At best, the sidewalks are rarely more than three-foot-wide strip of concrete (read: not wide enough to pass somebody without stepping on grass); at worst, there is no sidewalk at all. There is one place in the city with excellent sidewalks: downtown. Through the Great Streets program, truly walkable spaces have been created throughout the city center, providing elegant and accessible facilities for movement and making places like 2nd Street possible.

A great example of a fully protected bike lane outside of downtown can be found in Mueller

Programs like Great Streets need to be created for areas outside of downtown. Additional efforts to create full sidewalk networks in neighborhoods and protected mobility lanes (for bikes and scooters alike) need to be prioritized, not only so people can get to transit safely from their home, but so they can safely navigate their own neighborhoods without the difficulty of traversing both streets and front yards—or worse, around parked cars with other cars whizzing by.

A connected city also extends to the street grid. Creating a more gridded city improves movement for everyone, including cars. Connections can also be things as simple as bridges across bodies of water and railroad tracks that also allow for the passage of people and bikes, ensuring safe and easy access to all parts of town. Improved grids should also extend to creating a cohesive bike lane network. Along with providing safe places for individuals to use scooters, there have been studies that show protected bike lanes improve patronage of businesses along them. Given Austin’s pro-business environment and excellent weather conditions for most of the year, the choice to build more bike lanes is a no-brainer.

Moving Forward

Hopefully the land code reform will build upon recent policies like Affordability Unlocked and specifically address the problem of more housing that is affordable in the near future.

That said, the lack of truly human-centered design when it comes to streets and public space, as well as the inability to create more than one home on a significant portion of Austin, means that the city will simply be a place where most people will continue to drive from building to building because that is the safest and fastest way to get to where they need to go. For the reasons described above, as well as others we didn’t have time to get into—for example, the climate crisis—the status quo is no longer acceptable.

Austin needs to take bold action in zoning and urban space design to develop world-class neighborhoods that allow people of all ages and abilities to feel truly at home, both inside and outside their own four walls.

Top photo via Ryan Magsino.

About the Author

Ace Houston is an architect and founder of House Cosmopolitan, an architecture and design practice focused on celebrating culture and designing places where people belong. Ace is a resident of Seattle, however, as a fifth generation Texan, he also spends time in his adopted hometown of Austin.

Tactical urbanism is changing the way we approach city-building—here are five studies, toolkits, and guides to help you get started where you live.