L.A.'s Lost Transit

They don’t build neighborhoods like they used to. That’s at the root of the housing crisis that plagues rich coastal cities like New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

I’m going to use LA as an illustration. In the popular mind, Los Angeles is defined by the freeway, the automobile, and endless suburban sprawl. Four million people live in the city proper, and nineteen million live in the megalopolis. Four in five Angelenos drive to work, while only one in twenty takes mass transit.

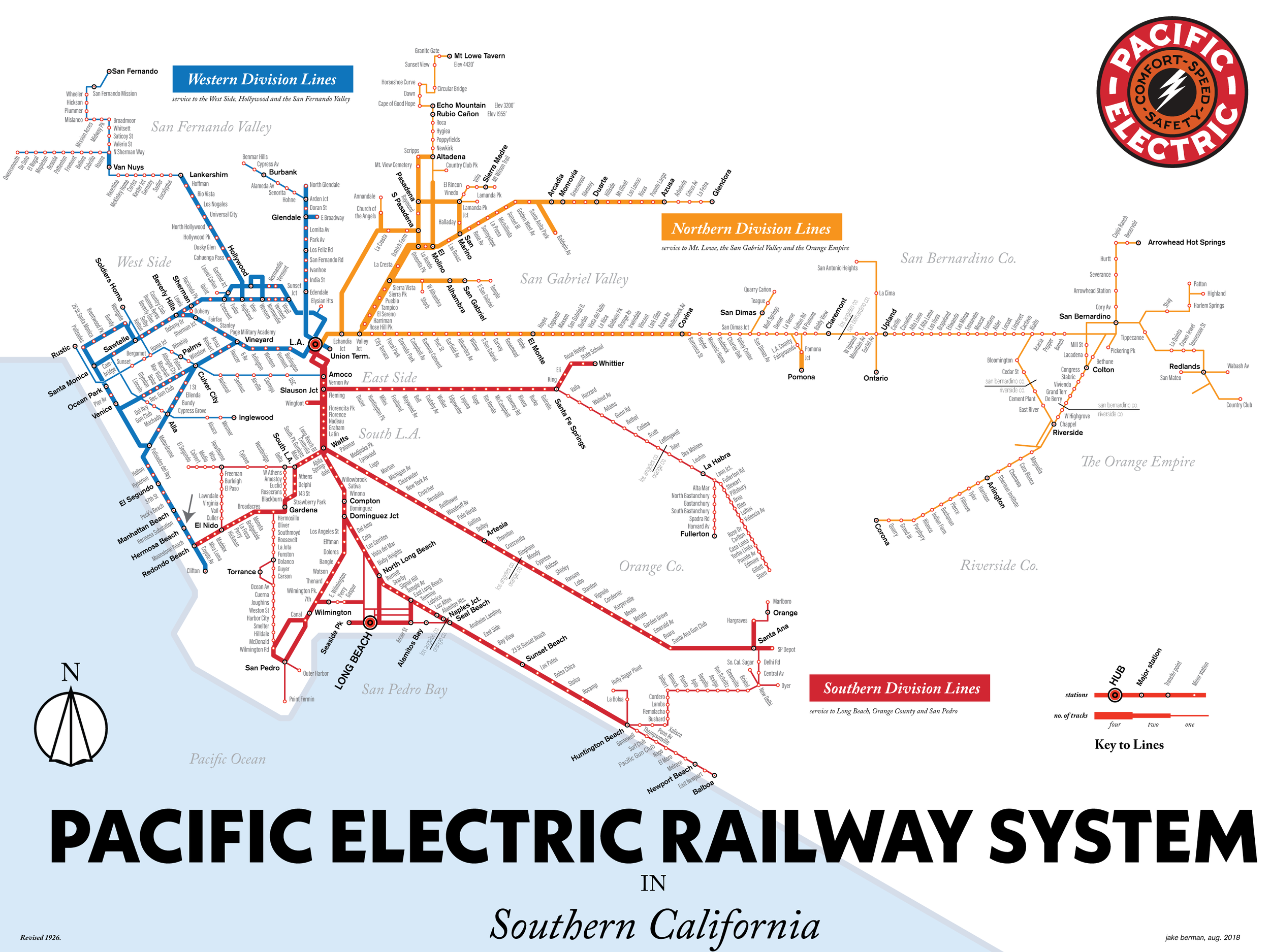

The horrible irony of all of this is that LA was never designed to be a car city. Quite the opposite. The bulk of Los Angeles was laid out before World War II around the old Red Car system of the Pacific Electric Railway. They just overlaid the postwar freeway system on top of it. At its peak, the Red Car system had over 1000 miles of track, but the system went into a terminal decline as the automobile and the bus gained popularity.

1926 Pacific Electric Railway System. Image credit: Jake Berman.

Modern LA Metro. Image credit: Jake Berman.

Let’s focus on one of those neighborhoods which was built around the old Red Cars. This is downtown Hermosa Beach, incorporated in 1907. Hermosa Beach, like the other streetcar suburbs of its era, came of age in the 1920s as a place for vacationers who’d take the Red Cars to the beach.

Hermosa Beach was designed to be traversed on foot or by streetcar. There’s relatively little parking, street-level retail is plentiful, and the residential neighborhoods have little of the gigantism that characterizes modern developments.

This is what dense, walkable LA neighborhoods look like. This is a Los Angeles suburb denser than Chicago and Philadelphia.

LA began rebuilding its rapid transit network in the 1980s, but its modern light rail and subway lines were never coupled with the kinds of land use changes that accompanied the Red Car system.

To illustrate, I’m going to go three miles away to the modern Redondo Beach station on LA’s C Line. The Redondo Beach station is surrounded by acres of parking with nary a store, home, or business in sight. According to LA Metro, less than a thousand passengers board at the station every day.

When LA rebuilt its mass transit network, it never bothered to change the zoning near its stations to accommodate the new infrastructure. That’s why you don’t see a single pedestrian, and every building nearby is designed to be approached by car. Even if you did happen to work nearby, a pedestrian would have to spend five or ten minutes crossing parking lots to get inside.

And it’s not as though the C Line station is in the middle of nowhere. Northrop Grumman has 5,600 employees within a half-mile radius of the Redondo station—but none of those buildings is designed to work in tandem with the station. Instead, the only way to get there is to schlep across acres and acres of parking.

The sad thing is, this pattern isn’t unique to Los Angeles at all. It’s virtually the standard in postwar urban planning.

But the good news is these types of issues are fixable.

In this, the San Francisco Bay Area has shown the way. There, Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) has built apartments to replace the acres of parking that were originally built around its 1970s-vintage rapid transit stations. Compare the street view of one from 2011 (left) with one from 2019 (right).

And because the parking lots are already owned by government authorities, it greatly simplifies questions of land acquisition—there are no local residents to displace, and no thorny questions of eminent domain.

The question is whether local officials in Los Angeles have the fortitude to follow BART’s example.

Top image credit: Jake Berman

About the Author

Jake Berman is an artist working on a project to map the lost subway and streetcar systems of North America. He lives in New York. Jake can be found on Twitter at @lostsubways, or on the Internet at http://lostsubways.com.

In this episode, Chuck explains that we’ve created a political climate where you either take a chainsaw to failing systems or you refuse to acknowledge that they’re failing. He then shows how the Strong Towns approach offers a better way. (Transcript included.)