Church to be Demolished for Self-Storage Facility

My family and I attend St. Francis Catholic Church in my hometown of Brainerd, Minnesota. This is where I went to church with my parents when I was growing up. We used to sit near my grandparents, informally in the same basic area of the church as we sit today. I remember my great-grandparents being present when I was younger. It was their generation that built the church, which replaces a smaller one up the street.

The loft in the back of the church houses a beautiful organ. The parish was fundraising for it when I was in high school. I remember pledging to donate $100, which was a huge sum of money for teenage me back then. It might be silly given my modest contribution to the effort, but I’ve always felt a sense of pride when the organ plays that I helped make it happen.

Part of that pride comes from my certainty that these gorgeous pipes in this beautiful cathedral will be heard for generations to come, not just by my descendants, but by the descendants of those who sit around me during weekly mass, as well as many newcomers I will never meet. Their services, their weddings, their solemn and their joyous days, will be more memorable because of how I humbly joined with many others to get the organ.

How conceited my certainty is.

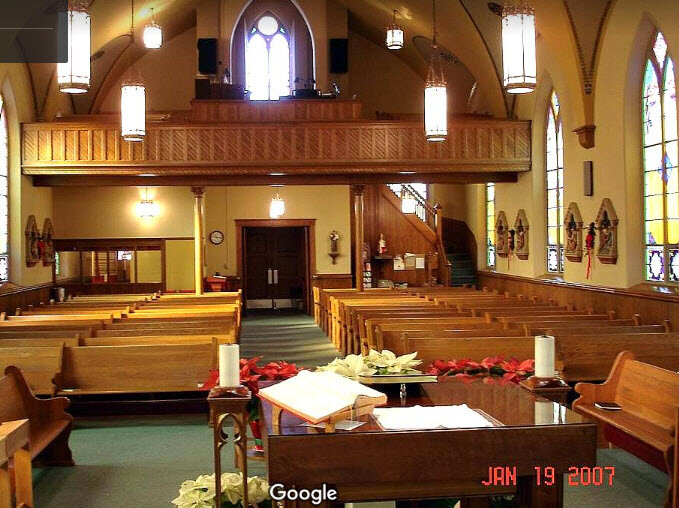

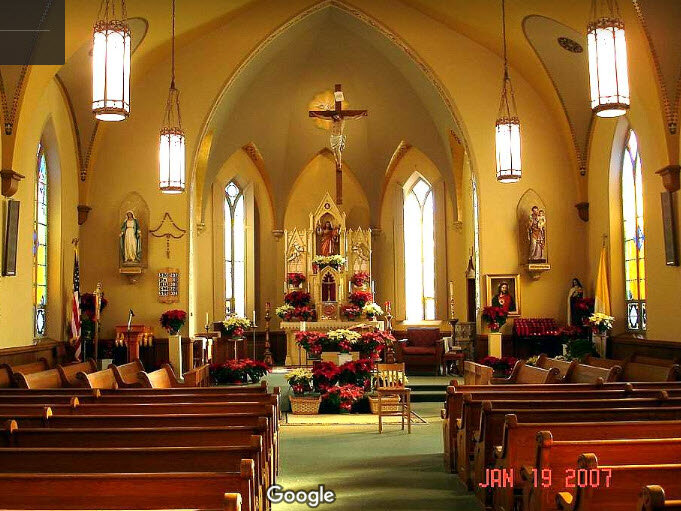

In Roseville, Michigan—a city three times the size of mine—a Catholic church larger in size than mine, and certainly rivaling it in beauty, is being torn down. This would be a tragedy on many levels, one that I struggle to fathom in the context of my own community, but that’s not the most jarring part.

The church is being torn down to make way for that most worthless and degrading of all urban land uses: storage units.

In nearly all urban settings, storage units are antithetical to a Strong Towns approach. They sell nothing. They employ essentially nobody. They provide little tax base. They make no use of the expensive sewer and water infrastructure that the public has provided to the site. In my days doing planning and engineering work for cities, I came to loathe the commercial slumlords who could cash flow their storage unit scheme on the backs of opaque public subsidies.

My own city’s industrial park is full of them, city officials seemingly proud that they could spend millions installing wide, industrial-strength roads with full public utilities, and have millions more obligated to maintain all of it, to get something that could just as easily have gone in a cornfield a mile up the road. No jobs. No sales. Comparatively no tax base.

Here’s what the developer in Roseville was quoted as saying in the local paper:

"We like being a part of this city and we want to help the community grow," said Todd Clark, president of My Space Self Storage. "This will help create a downtown area and will be a positive impact on the neighborhood."

Developers holding concept art of the new storage space. Photo from the Macomb Daily.

It’s difficult to see how this will help the community grow, let alone do anything for a downtown area that is non-existent in any of the immediately surrounding neighborhoods. It’s also difficult to fault this developer for bottom-feeding, however. One look and it’s clear that this community did this damage to itself.

From the six-lane stroad right outside the door of the church to the collection of strip malls, franchise stores, and parking lots that surround it, whatever value the historic church might have created for properties has long dissipated. So devalued is the ground and neighborhood around this building that—you guessed it—additional subsidies are needed to make this transaction happen.

This past summer, the City Council approved creating a commercial rehabilitation district for the property as well as for Erin United Presbyterian Church near Common Road. The districts were created in a proactive move that could provide financial incentives to encourage redevelopment opportunities.

It's not lost on me that the Catholic Church has been a partner in this decline. The word “parish” descends from the Greek paroikia which means to “dwell beside,” yet nobody any longer dwells beside this church. There is plenty of parking, however.

As the Detroit metro area grew in the American style of development, the Catholic Church responded here, and across the country, by embracing the change. The referenced article indicates that Sacred Heart Parish was “split up numerous times to create new parishes across Macomb County,” a split that mirrors the splits happening in formerly cohesive neighborhoods across the same area.

Almost certainly dwelling beside those new parishes is plenty of parking—although, as has become apparent, having great parking does not create the community the Church needs to be meaningful. I would argue that it reinforces the opposite tendency: disconnection, the lack of community. This is a tragedy across many dimensions.

A final note from the article:

As part of the conditional rezoning, the company agreed to a covenant that prohibits adding on an adult video store or bookstores, mortuary establishments, a motel, massage parlor or sexually oriented business, or "any use that is contrary to the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church."

What part of any of this is consistent with the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church? Tearing down an historic cathedral to build storage units that will house our excess material goods is about the perfect metaphor for modern society. And, too often, the modern Church. Those of us who value the yolk of a parish—the calling to dwell beside, in communion with others—must recognize how fragile it is, how the work is essential to both the experience and also the future we all like to believe we’re passing on.

Top photo from the Michigan Stained Glass Census. Photos of the interior of Sacred Heart from Google via Creative Commons.

North Carolina lawmakers have joined forces across party lines to make housing easier to build—here’s what they’re proposing.